Tsar and Khan in black and white: Treaties between Russia and China (1689-1881)

Sitting on the shelves of the Special Collections at Leiden University is a bundle of rare reprints of treaties between Russia and China. Important, because copies of original treaties are not something that we, ordinary mortals, may consult.

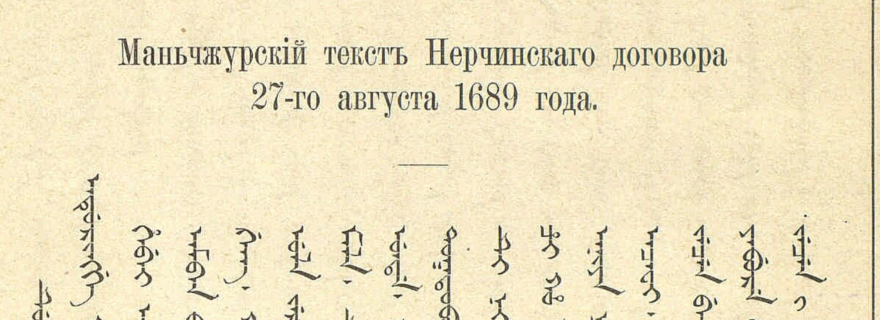

Sitting on the shelves of the Special Collections at Leiden University is a bundle of treaties between Russia and China, titled Sbornik dogovorov rossi s kitaem (Sbornik, hereafter). Printed in 1889, this collection consists of 21 reprinted agreements between China and Russia, starting with the “Treaty of Nerchinsk” of 1689 (see image 1, Manchu version) and ending with the “Ratification protocol to the Treaty of St Petersburg” of 1881. This reprint is rare[1] and important, not in the least because copies of the original treaties are not something that we, ordinary mortals, may consult.

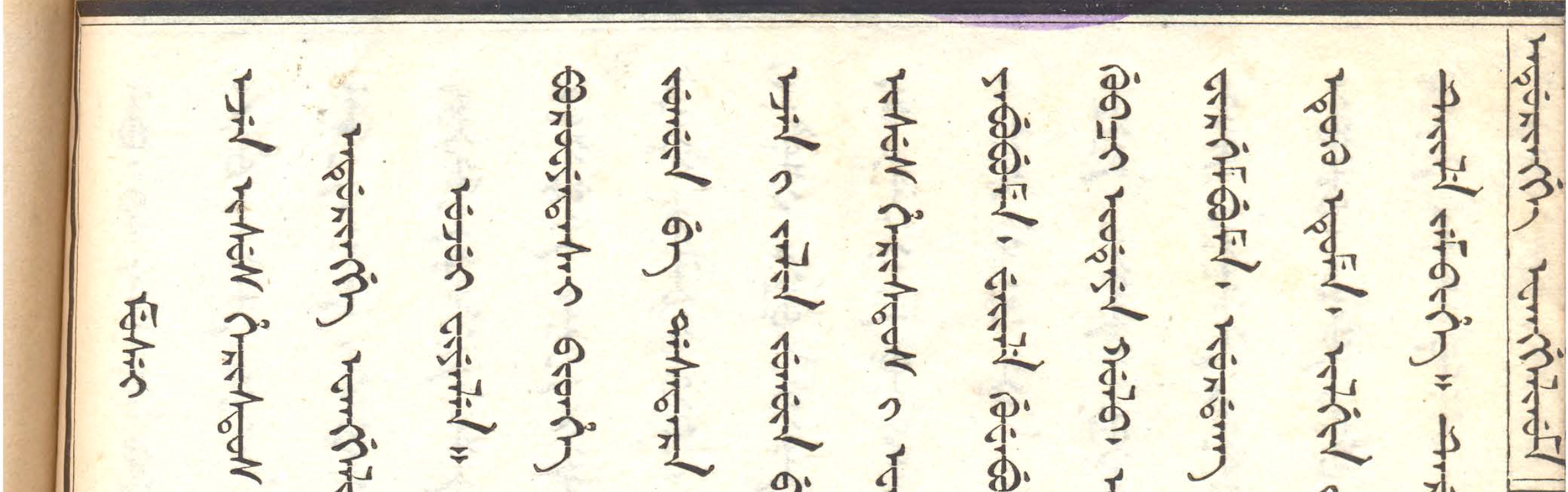

Sbornik was commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and printed on the presses of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg. The Manchu letters in Sbornik are from the same presses as the one used for the first Gospel translation in the 1820s[2]; and also for the first 1000 copies of the translation of the New Testament into Manchu for the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1835 (The Special Collections has a copy). Clearly, already by looking at its typography, Sbornik is telling the story of the then growing global interconnectedness.

The first Page of the Gospel of Matthew, 1822.

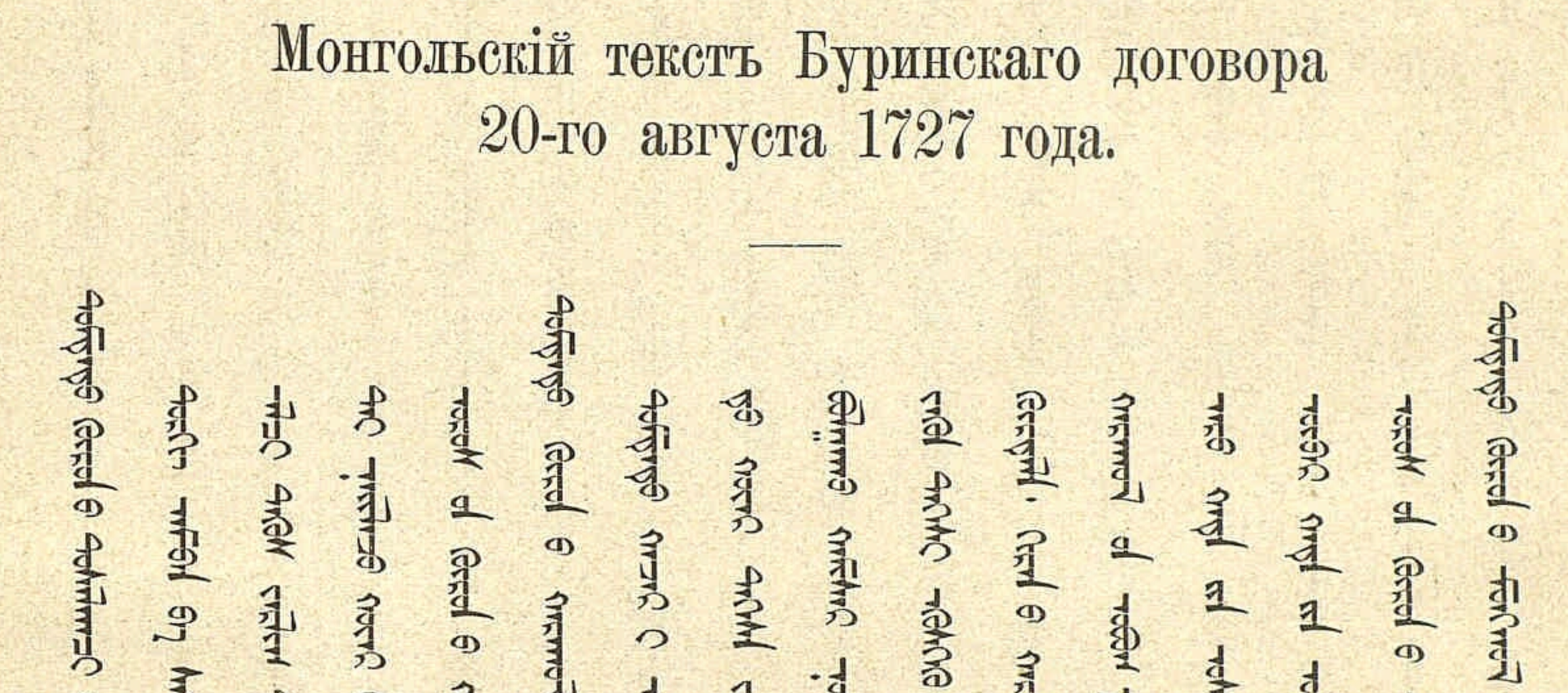

Also visually, Sbornik is a very direct confrontation with the multilingual reality in which the negotiations took place between the representatives of the Tsar and the Khan of the Daiqing (and thus Emperor of China). No less than six languages were used to seal the agreements: Manchu, Russian, Latin, Mongolian, Chinese. The introduction by the Ministry itself reads:

In view of the fact that all previous editions of our treaties with China are completely out of print, the commanders-in-chief of the regions adjacent to that country have recently begun to request from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs that those treaties, whose provisions are required quite frequently by our border authorities, should be re-edited. When the Asiatic Department undertook to supply this urgent need, it could not ignore the fact that in all previous editions of the Russian/Chinese treaties only the Russian text was published whereas none of the Chinese, Manchurian, or Mongolian versions have ever been published so that the latter have been as good as inaccessible to the experts occupied with the study of China. Therefore, it is the objective of the present edition to meet both the needs of our border administrations and diplomatic representations and the legitimate demands of those experts, whose research work on China, in view of the continued development of our relations with that country, should be met with ever increasing interest in our Russian society.[3]

The reprint was thus urgent, and without it we might only have known the Russian versions of the agreements. The choice to add a French rendition of treaties 8 to 21 was a Ministerial afterthought. While French was not included in the original treaties, it was added to Sbornik ‘to make the collection accessible to foreigners too.’[4] Leiden University Law Library purchased a copy of the 1979 reprint (introduced and prepared by Michael Weiers) of the 1889 reprint. The collection, however, is of interest to an audience far beyond the Faculty of Law. At present, for example, with the support of Leiden University Faculty of Humanities, Sbornik will find its way to several courses in Leiden, including the Global History course (560 students this year. 2019) within the BA International Studies; on the basis of QingMaps.org new educational material is being developed that will map and contextualize the content of the treaties. But, within such a project, on the basis of which version are we providing English translations then? Does it even matter?

Yes, it does. The Russian, Manchu and Latin version of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, for example, differ considerably in content and length. My Manchu students[5] are now reading the Manchu version, which is believed to be the original version.[6] It is my hope that they, together with their peers from other studies, will be able to trace the changes in meaning that it underwent from one language to the next. This is the joy of working with “parallel” multilingual texts. They are always more than mere translations of each other, and discrepancies, intended or not, are not without consequences. Sbornik, to me underscores the importance of Leiden University Libraries continued investment in collecting parallel editions to underscore that Leiden University is the university of languages and philology.

Blog post by: Fresco SAM-SIN, Lecturer at the Leiden Institute for Area Studies at Leiden University.

The first Page of the Treaty of Bur of 1727, in printed edition of 1889

[1] Around 15 copies outside Russia. Digital editions are available now via the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek and the Russian federal electronic storage of the Presidential Library.

[2] Confirmed by Jo de Baerdemaeker (Typojo), specialist in the history of Mongolian and Manchu letters. The Manchu type is “Mandschurisch Gr.16”, the Mongolian is ‘Mongolisch Gr.16’ from the same office. Both from the printing office of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg.

[3] Translation comes from a reprint of the reprint, prepared and introduced by Michael Weiers (1979) Die Verträge zwischen Russland und China, 1689-1881: Faksimile der 1889 in Sankt Petersburg erschienenen Sammlung mit den Vertragstexten in russischer, lateinischer und französischer, sowie chinesischer, mandschurischer und mongolischer Sprache. P. II

[4] Ibidem, p. IV

[5] At present Marin Götte and Merijn Flippo.

[6] Walter Fuchs. “Der Russisch-Chinesische Vertrag Von Nertschinsk Vom Jahre 1689 Eine Textkrische Betrachtung” in Monumenta Serica 4 (1), pp. 546-593.