Tricks ánd Treats: Medieval Machines from the Middle East

Medieval Arabic manuscripts in the Leiden University Libraries with colourful images of intricate machinery are part of a tradition that goes back a long way in the Middle East.

Have you ever heard of Ugears™, the wooden toy from Ukraine? Well, until recently I hadn’t. They are assembly kits to create moving mechanical objects such as clocks, car engines, terrestrial globes, a windmill, and a combination lock, some of them consisting of more than 700 parts. People have always been intrigued by complicated mechanical devices. A striking example from the 18th – 19th century is the ‘Mechanical Turk’, a figure of a turbaned Turk sitting on top of a large wooden box, who could play – and win – a game of chess. Unfortunately, this automaton of Austro-Hungarian origin eventually turned out to be a hoax: the large box contained an expert chess player of diminutive size who cleverly operated the ‘Turk’ sitting above him. Even Napoleon played against him – and lost. For the Dutchmen among us: the same Oriental style can be seen in the life-sized ‘automaton’ called ‘The Fakir and the Gardener’ in the Efteling fairytale theme park, in which a flute-playing fakir sitting on a carpet flies between the two towers of a palace.

Irrigation and the Measurement of Time in the Middle East

In the semi-arid Middle East and North Africa, the irrigation of crops has always been a matter of primary concern. People from long bygone eras took recourse to mechanical tools to ease the burden of raising water to a higher level with the purpose of filling irrigation canals. Machines such as the saqiya (operated by animal power) or the noria (powered by running water with the help of a water wheel) long predate the introduction of Western technology and go back to Oriental Antiquity. The Archimedean screw, a water-raising device based on the idea of the upward-moving thread of a large screw inside a tube, is erroneously attributed to the Greek scholar Archimedes of Syracuse, who lived in the third century BCE. In fact, he only described the instrument when he saw one on a journey to Egypt. Likewise, the invention of the water clock or klepsydra has often been attributed to the Ancient Greeks, but it has in fact been around in the Middle East since the 16th century BCE.

Al-Jazari and his Book of Ingenious Devices

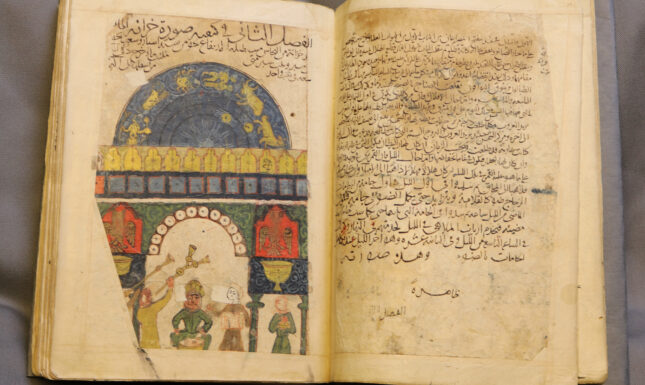

At the opulent royal courts of the Islamic Middle East, the passion for extravagant luxury transformed these humble machines for everyday use into expensive novelties meant for play or amusement. Most of these objects have turned to dust, but many are preserved in beautifully illustrated Arabic manuscripts. An eminent example is the ‘Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Devices’ (Kitab fi Maʿrifat al-Hiyal al-Handasiyah), written in 1206 CE by Ismaʿil ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari (1136-1206). Little is known about his life, apart from what he tells about himself in his book. ‘Al-Jazari’ probably refers to the Jazira or Mesopotamia, the lands between the upper reaches of the Tigris and the Euphrates. He spent his working life as an engineer and inventor in the service of the Artuqids, a petty dynasty based at Amid (now Diyarbakır in Southeast Turkey). During al-Jazari’s lifetime, the Artuqids were vassals of the renowned Sultan Saladin, who ruled over Syria, Egypt and Palestine.

Tricks and Treats

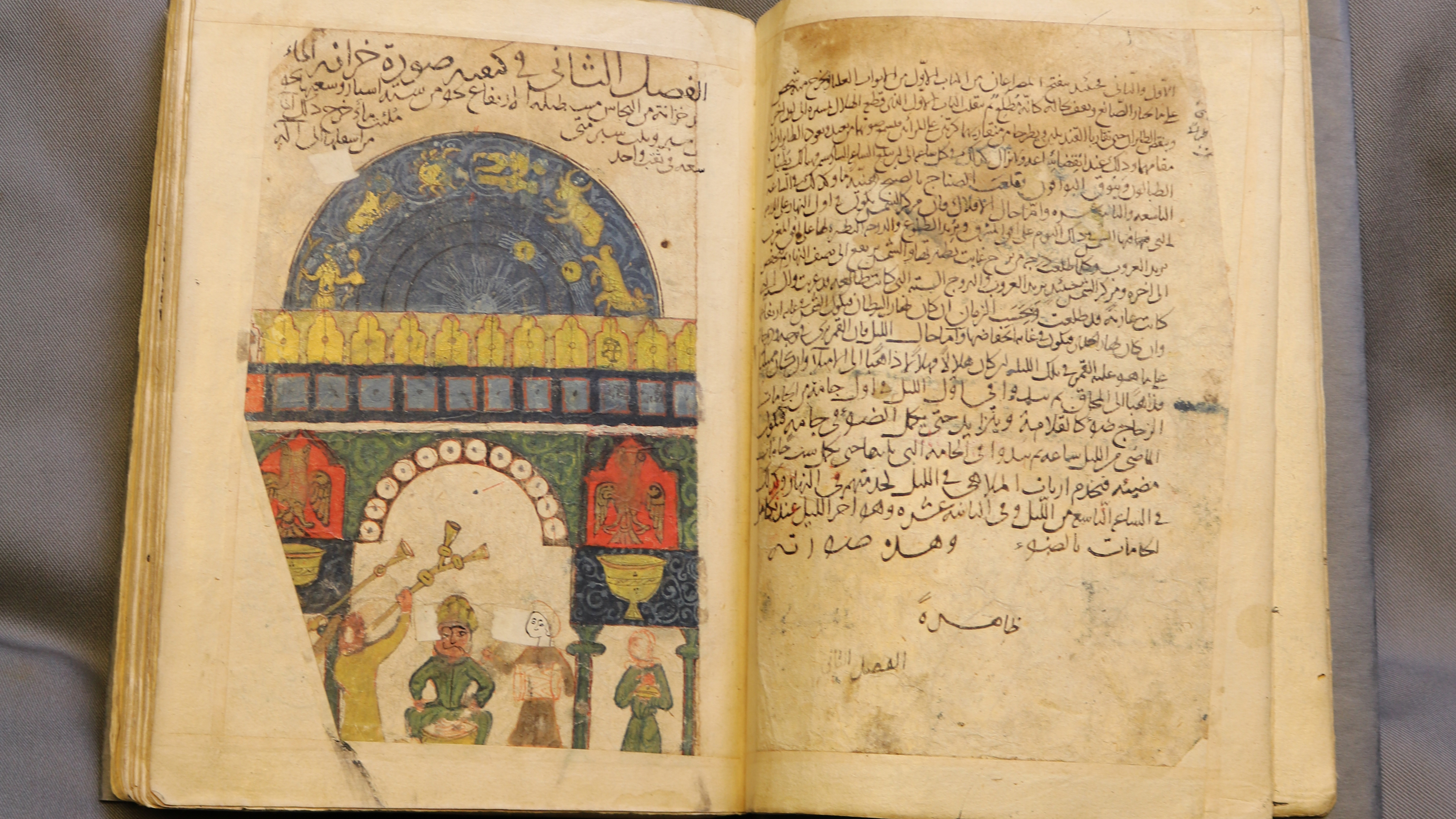

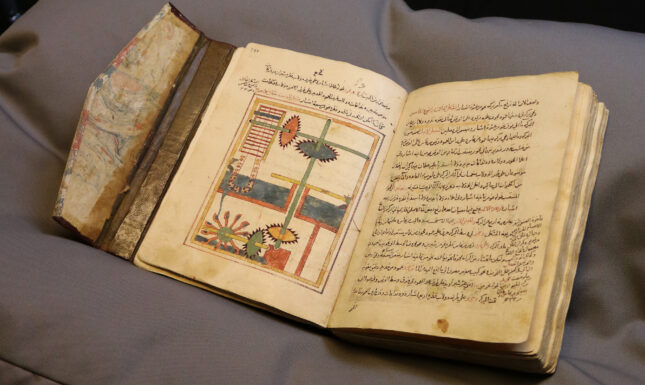

In his book, of which many copies survive, al-Jazari describes in meticulous detail many sophisticated machines, illustrated with beautiful miniatures. The quality of the illustrations and descriptions is such that it allowed modern engineers to actually build working replicas. But the sheer number of surviving copies indicate that most Medieval readers used it as a coffee table book for the fun of it. An English translation was published by Donald R. Hill in 1974.

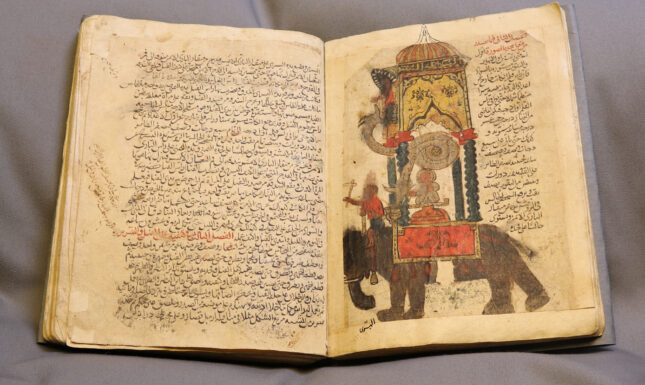

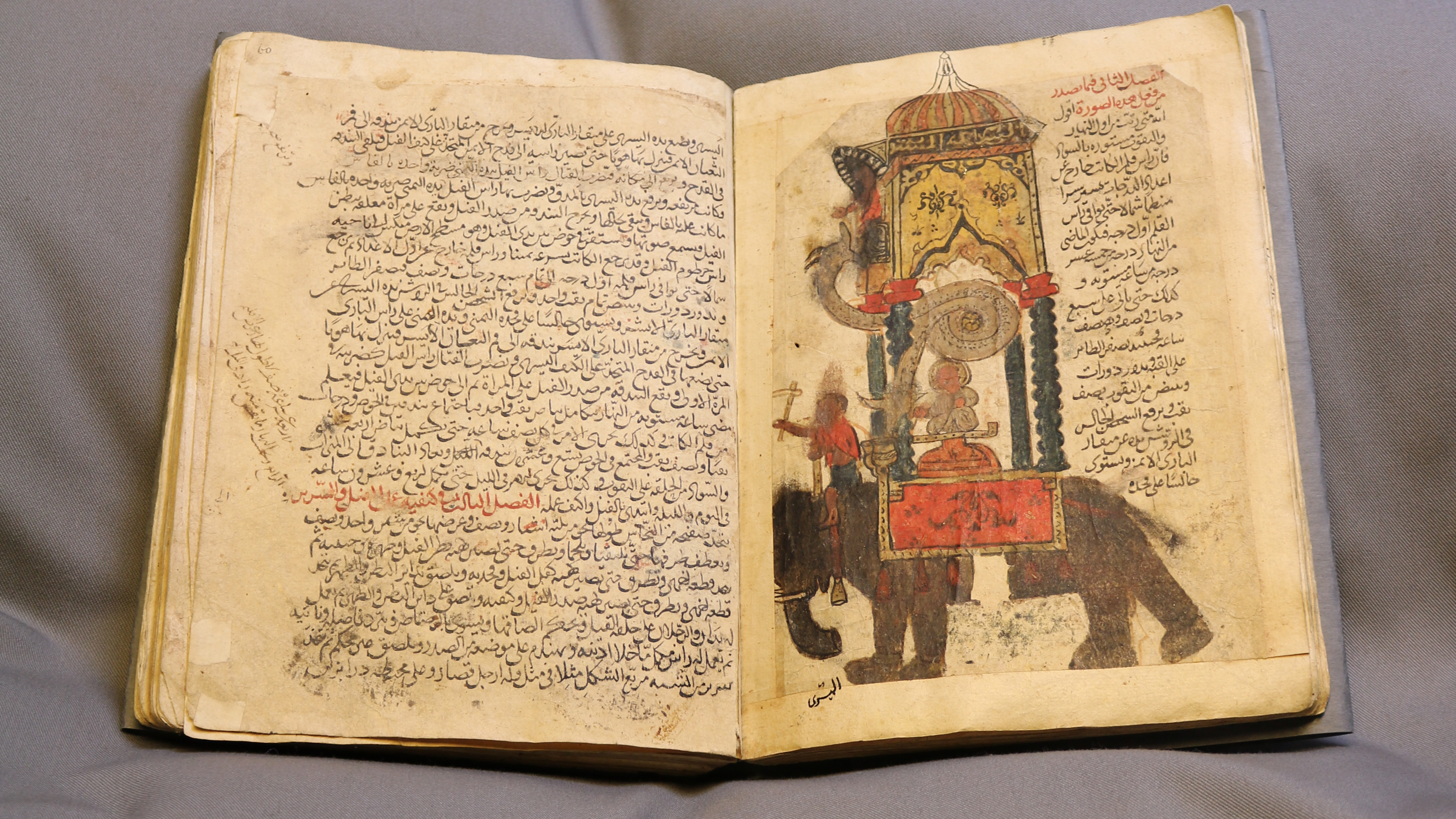

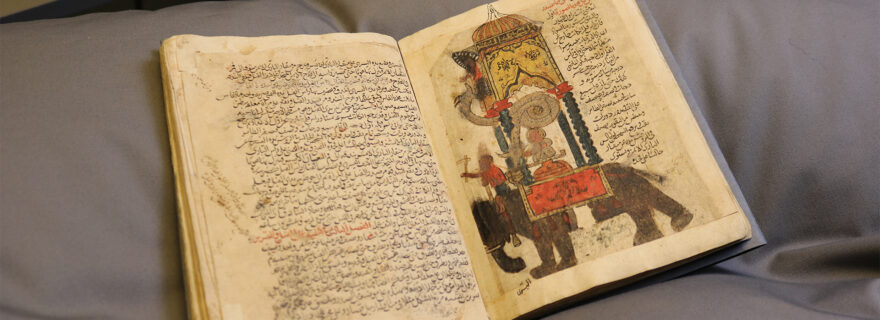

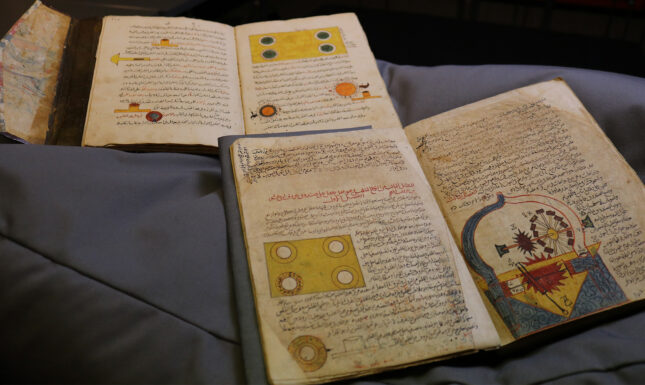

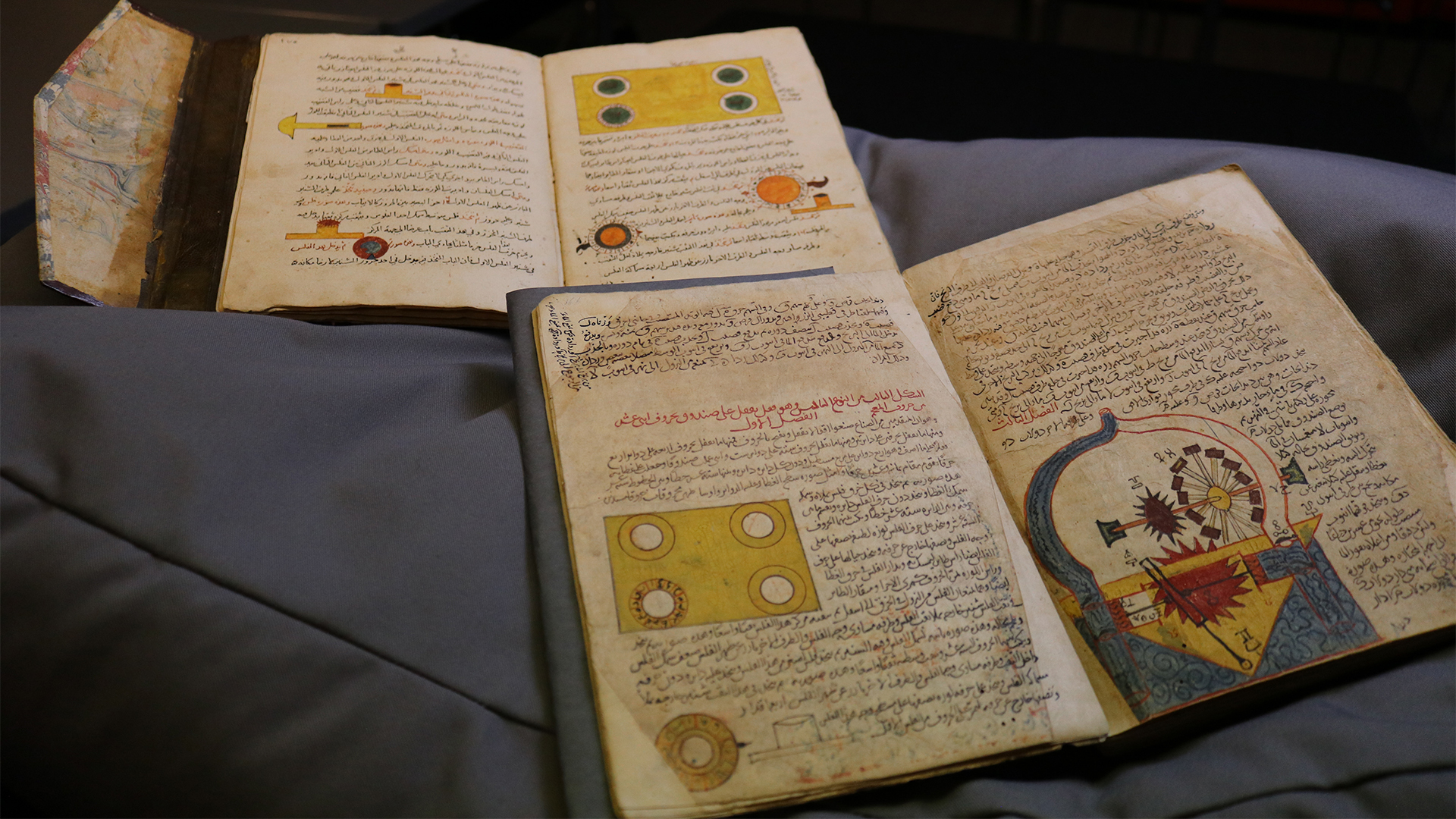

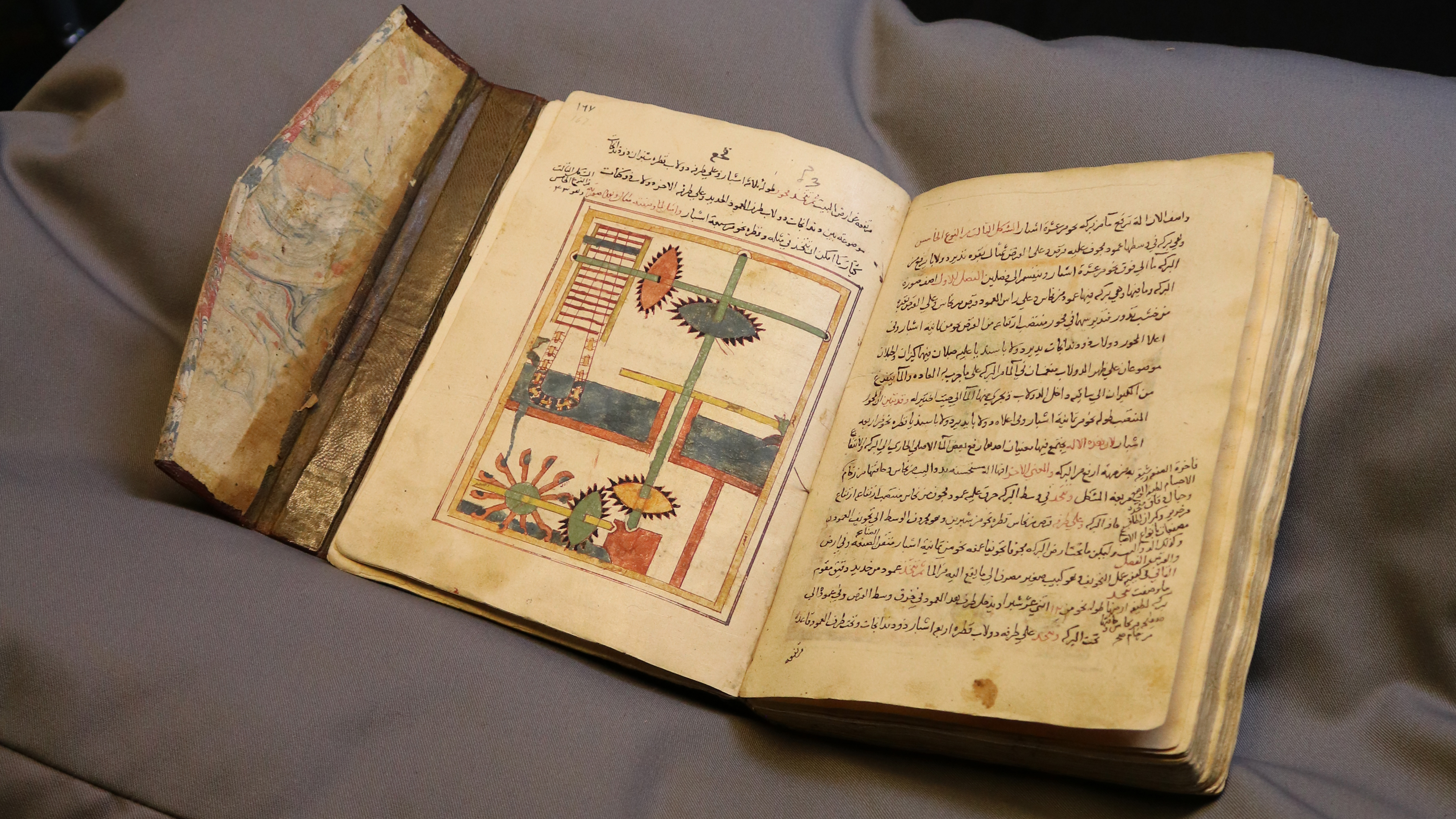

Leiden University Libraries possesses two manuscripts of the text: Or. 656, dated 1561 CE, and Or. 117, undated but certainly older than the other one. The first manuscript features the model of a water-raising machine with a hidden trick, in which water is raised from an invisible lower pool to a visible upper pool. The scoop wheel (below left), powered by running water, sets the machine above in motion. On the revolving yellow platform (centre right) there is space for an artificial ox (absent in the Leiden manuscript), who appears to be walking around in circles to set the cogwheels in motion, just like an ordinary saqiya.

A truly wondrous machine is the Elephant Clock. A mahout or elephant rider, sitting on the neck of the Elephant, hits the skull of the elephant with his mallet to mark the time. Simultaneously, a secretary sitting on a dais indicates the correct time with his pen. The required energy is provided by a series of metal balls in a secret container, which is dispensed into the mouth of a tilting snake at regular intervals. Most of these details are completely superfluous, but an absolute delight to behold.