To steal a book

A unique collection of Chinese underground poetry attracts all kind of visitors...

In the summer of 1991, I spent two and a half months visiting poets in some of the hotbeds of Chinese poetry: Beijing, Chengdu, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. The mad carnival of the 1980s – when you’d trip over poetry manifestos in the streets – had given way to a subdued atmosphere, at once tense and resigned. A government crackdown in the cultural realm once more showed the importance of what were called “underground” or “unofficial” poetry journals, not unlike the samizdat or “self-published” journals of Soviet Russia.

This was pre-internet and few people had private telephones, but I was very effectively being shipped through the country from one stop to the next, through a tight-knit network of poets. As I did interview after interview, two things became clear. The oral history of unofficial poetry had to be turned into a written history, and the unofficial journals, legendary already in their own time and as fragile as they were precious, had to be made accessible outside China. The poets were generous and liked the idea of their work getting foreign exposure. By the end of my trip I had enough material to start what has since become a unique collection in the Leiden University Library, used by visitors from all over the world.

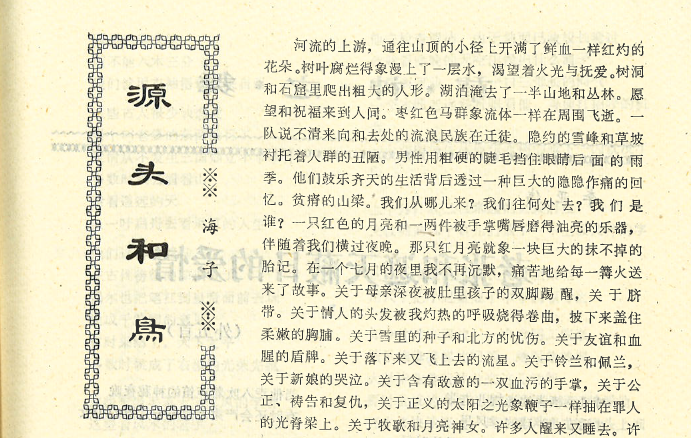

In Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, a dozen poets filled my notebook with stories and my backpack with journals. One was Contemporary Chinese Experimental Poetry 中国当代实验诗歌, from 1985, famous for the impact its single issue had had. Typical of the 1980s, it embraced the encounter with foreign literature, in this case embodied by Daozi’s Chinese translation of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” a signature text of the Beat Generation. On the Chinese side, made in Fuling city and featuring many Sichuan authors, the journal also contained work by poets based in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Kunming, and so on. This included “The Source and the Bird,” a poetic essay by Haizi, a young poet in Beijing who was loved by some for his talent and hated by others for his megalomania.

Haizi killed himself in March 1989. His suicide has turned him into a god, in a lineage of poet-suicides that goes back to antiquity and continues in China today. And so one day a visitor to the Leiden collection abused our trust and sliced out “The Source and the Bird” from Contemporary Chinese Experimental Poetry. We found out when the next Haizi researcher reported it, in 2010.

In one of the ur-texts of modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun’s 1919 short story “Kong Yiji,” a caricature of a scholar fallen on hard times claims that “to purloin a book shouldn’t count as theft.” Variations on this theme include the assertion that “to steal a book is an elegant offense.” So what about stealing a single page? But all I felt was anger. Recently, however, when working with curator Marc Gilbert on plans for digitizing the collection, I was overjoyed to realize that the journal was one of several of which we have two copies. We are giving the doubles away to other collectors, but not this one. Here, the luxury of the second copy allows us to lean back and view the theft as new evidence for Haizi’s apotheosis, and for the meaning of poethood in China at large. A material loss, then, but an intellectual gain – and a way out of my anger, perhaps even allowing for a grudging nod toward the “elegance” of stealing books. Just because we got lucky.

Read more about the unofficial poetry journals in “From China with Love”

Guest author of this post Professor Maghiel van Crevel