The Syair Tabut, an overlooked scroll

This long overlooked scroll, the Malay language Syair Tabut, is the only eyewitness account of the last Muharram commemorations in Singapore in 1864, a practice still banned to this day.

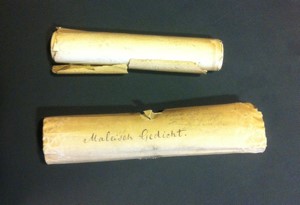

The Syair Tabut is a 146-quatrain Malay-language, Jawi-script syair written in 1864 from the collection of H. C. Klinkert, held in the Leiden University library’s Special Collections. The Syair, with its shelfmark Kl 191, seems for whatever reason to have been omitted from earlier manuscript catalogues (e.g. van Ronkel 1921, Ali 1985, both of which stop at Kl 190). Being part-lithograph and part-manuscript, it also escaped mention in Ian Proudfoot’s survey of early Malay printed books (1993). It finally made an appearance in Teuku Iskandar’s Catalogue in 1999. The unassuming scroll bundle, pictured here, has only the notation “Maleisch Gedicht”, or “Malay Poem”, on its covering wrap.

Iskandar, at the end of the first volume of his catalogue, records:

1571. Kl. 191 Syair Tabut Scroll, European laid paper, 228×13½ cm.; ca. 53 lines per 50 cm.; lithographed text (fine writing); only 64½ cm at the end written by hand (bad handwriting); written by Encik Ali at Bangkahulu, assistant (bantuan) to Syaikh Muhammad Ali of Bengali descent; the writing was finished in 1281/1864–65.

A syair on the celebration of the death of Hasan and Husain (grandsons of the Prophet) in Bencoolen; the Bengalis play an important role in this celebration. (Iskandar 1999: 748)

While reading catalogues cover-to-cover is not necessarily an enjoyable exercise, my colleagues and I were delighted to encounter this reference. As part of the European Research Council project ‘Musical Transitions to European Colonialism in the Eastern Indian Ocean’, led by Katherine Butler Schofield and based at King’s College London (2011–15), we were hunting for sources that might shed light on musical practices on both sides of the Bay of Bengal, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, and especially any that related to connections between South and Southeast Asia. A text such as the Syair Tabut promised much—the Shi‘i Muharram commemorations being a noisy, public, and indeed a musical event of public ritual mourning.

However, we were to discover that Iskandar had made a crucial, though entirely understandable mistake. The events described in the Syair did not take place in Bencoolen/Bengkulu, West Sumatra (though that would have made perfect sense, given the scholarship on Muharram there by Margaret Kartomi, Michael Feener, and Paul Mason, all of whom highlights the involvement of South Asian emigres in Muharram commemorations) but in fact in Singapore. The author of the Syair describes himself as “anak Bangkahulu”, or a “son of Bengkulu”, in the third quatrain, and it is not until quite late on in the poem that he refers to definite place names in Singapore—Kampung Susu, Kampung Glam, Kampung Bengkulu, Teluk Ayer, and Singapore itself.

Once we realized the syair’s true setting (and it took us much longer than we may like to admit!), the way was open to seeing this scroll for what it is: a truly eye-opening account of an event of great historical importance. The Syair Tabut, while functionally anonymous, is the only Malay-language eye-witness account of the 1864 Muharram commemorations at Singapore: commemorations that turned violent, with clashes between rival “secret societies”, and between them and the colonial police forces, that were to lead to two separate criminal trials of especial significance, and ultimately a colonial ban on Muharram processions in Singapore that has never been lifted.

My colleagues and I spent a long time poring over the Jawi script of the scroll. The occurrence of Indian-derived terms, unknown in other manuscripts of the period, and frequently not to be found in contemporary or historical Malay dictionaries, was a particular challenge. Nevertheless, it demonstrated the value of the collaborative approach that we took to deciphering the text. Some puzzles remain unsolved, to this we happily confess to in both our transcription/translation and accompanying article. (In fact, one may have been solved since publication. We had speculated that the word ‘kudu’ for tazia or tabut may have Tamil origins; over coffee after Julia Byl and I spoke at Leiden in November 2017, Mahmood Kooria observed that the Malayalam word കൂടു was a very likely option, and we are grateful to him for that correction.) These puzzles seem to have struck Klinkert himself: while the scroll has obviously lain unstudied for quite some time, blue pencil markings underline the words and run alongside the lines that frequently were the most difficult for us to make sense of, suggesting that Klinkert had examined the text, presumably in the course of preparing his 1892 Malay dictionary.

Kl 190, the Syair Kombang Mengindra, covering wrap and storage box.

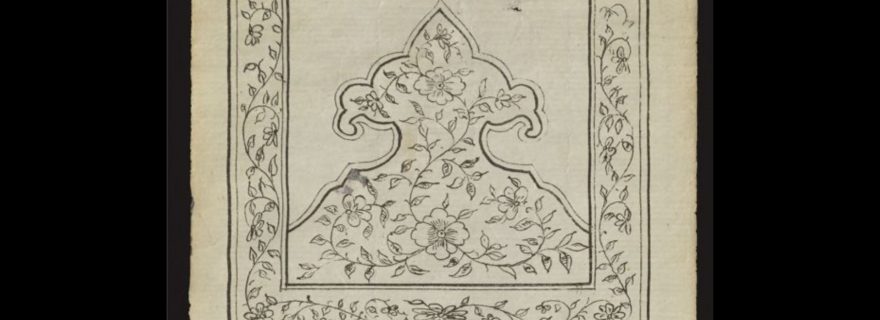

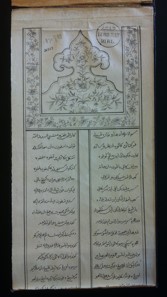

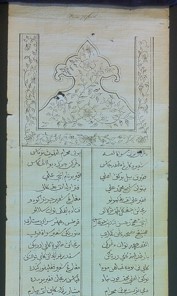

The scroll of the Syair Tabut shares certain physical properties with other Jawi texts in the Leiden collections. It is stored and wrapped in the same manner as its immediate predecessor in the collection Kl 190, the Syair Kombang Mengindra, though at this point the similarities end. Kl 190 has a little more detail on its wrap, including a pencilled “Coll. Klinkert”, but the scroll itself is quite different in its presentation, being a manuscript. The Syair Tabut’s more obvious relative is in the copy of the Syair Kampung Gelam Terbakar of Munsyi Abdullah, also held in Leiden (O 870 G 89). The latter syair is stored folded in the form of a concertina, but its physical properties—the layout of the text, the similarities in the scribal hand, and perhaps more tellingly the ornamental header—mark both out as products of the Singapore Mission Press run by the Reverend Benjamin Keasberry.

It would be illuminating to know how and why the Syair Tabut entered Klinkert’s collection. Similarly, how many copies were made, how and where did it circulate, and what if any contemporary impact it had, are questions I for one would dearly like to have answered. What we do know is that it provided an account of inter-group competition, and the role the police played in the resulting violence, that was significantly at odds with that found in colonial newspapers and government papers. But more than that: it is a vibrant, witty, and entertaining literary text, that paints a picture, in lyrical colour, of a commemoration that, while it had its raucous elements, still retained a profound sense of devotional piety and lamentation for its participants. This is a picture far more compelling than the monochrome of colonial court accounts and patronising journalistic coverage, and it has been our great pleasure to rediscover it after years lying in obscurity.

Left:O 870 G 89 Syair Kampung Gelam Terbakar, opening lines

Right: Kl 191 Syair Tabut, opening lines

Dr David Lunn is a Senior Teaching Fellow and Research Associate in South Asian and Postcolonial Studies in the School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics.

Our transcription and translation, and accompanying article:

David Lunn and Julia Byl, 2017. ‘‘One story ends and another begins’: Reading the Syair Tabut of Encik Ali’. Indonesia and the Malay World 45, 133, pp. 391–420 (no subscription? try this free eprints link).

Julia Byl, Raja Iskandar bin Raja Halid, David Lunn & Jenny McCallum, 2017. ‘The Syair Tabut of Encik Ali: A Malay account of Muharram at Singapore, 1864’, Indonesia and the Malay World 45, 133, pp. 421–38 (no subscription? try this free eprints link).

A PDF of the Syair, with photographs by Jenny McCallum, made available by kind permission of the Library, is also hosted on the journal website.

References

Ali, Hj. Wan Mamat. 1985. Katalog Manuskrip Melayu di Belanda/Catalogue of Malay Manuscripts in the Netherlands. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia.

Feener, R. M. 1999. ‘Tabut: Muharram observances in the history of Bengkulu’. Studia Islamika 6 (2): 87–130.

Feener, R. M. 2015. ‘‘Alid piety and state-sponsored spectacle: Tabot tradition in Bengkulu, Sumatra’. In C. Formichi and R.M. Feener (eds), Shi’ism in Southeast Asia: ‘Alid piety and sectarian constructions. London: Hurst, pp. 187–20.

Iskandar, Teuku. 1999. Catalogue of Malay, Minangkabau, and South Sumatran manuscripts in the Netherlands, vol. 1. Leiden: Documentatiebureau Islam-Christendom.

Kartomi, M. J. 1986. ‘Tabut – a Shi’a ritual transplanted from India to Sumatra’. In David P. Chandler and M.C. Ricklefs (eds), Nineteenth and twentieth century Indonesia: essays in honour of J. D. Legge. Clayton: Monash University, pp. 141–62.

Klinkert, H. C., 1892. Nieuw Maleisch-Nederlandsch zakwoordenboek. Leiden: Brill.

Mason, P. 2016. ‘Fight-dancing and the festival: Tabuik in Pariaman, Indonesia and Iemanjá in

Salvador da Bahia, Brazil’. Martial Arts Studies 2: 71–90.

Proudfoot, I. 1993. Early Malay printed books. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaysia

van Ronkel, P. S. 1921. Supplement-Catalogus der Maleische en Minangkabausche handschriften in de Leidsche Universiteits-Bibliotheek.