The success story of Jacques Aanstoots, electrical engineer in the Dutch East Indies: part 1

The Leiden Special Collections hold the diaries of Jacques Aanstoots (1910-1912). They attract the attention of the Dutch readership for the name of the writer alone: ‘aanstoot’ means ‘offence’ in Dutch. Who was he? What did he write? And how did ‘his’ writings function?

Jacques Aanstoots

On January 5, 1873, at five o'clock in the afternoon, a boy was born in a house on Rotterdam's Oostsingel. He was named after his father, Jacques Aanstoots (1832-1896). His mother's name was Cornelia Wilhelmina Le Noir (1834-1892). The born and bred Rotterdammers had found each other later in life after their earlier spouses had died at a young age. Cornelia ran a café. Jacques senior, like his father, was a watchmaker.

Jacques junior, to whom I will confine myself here, would not follow his parents. He did not become a watchmaker or a pub owner, nor would he stay in the port city. Around 1900, he worked in Amsterdam for some time as (assistant) telegraph supervisor. He helped with the construction of the first underground long-distance telephone cable in the Netherlands, which was laid between Amsterdam and Haarlem in 1904. At the time the cable was laid, Aanstoots was already married to Sophia (Sophie) Pijper (1876-1942), three years younger, who also had a job in the capital as a telegrapher. Together they had one daughter. On June 25, 1900, more than a year after they were married, Everdina Sophia Maria (Titi) Aanstoots was born in Amsterdam.

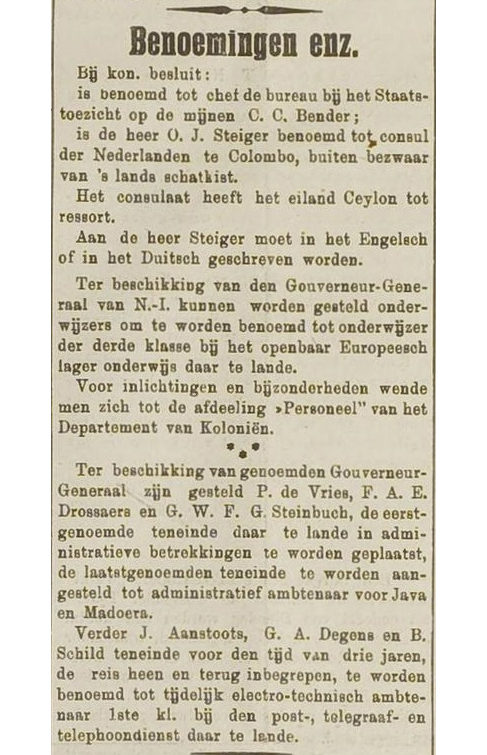

In 1910, Aanstoots decided to join the Post, Telegraph and Telephone Service (PTT) in the Dutch East Indies. As an electrical engineer first class, he would work for the state-owned company for three years. During that period, he helped strengthen the connection between the Dutch East Indies and Europe by laying telegraph cables. Two of his colleagues, including Gerard Degens (1878-1945) from Rotterdam, made the same choice. Aanstoots bought a white tropical suit at Wiener and Van Witsen in the Rotterdam Hoogstraat, said goodbye to his daughter and wife, and headed for Batavia, first class on the steamship Grotius.

Aanstoots does not seem to have had a particularly strong connection with the Malay Archipelago back then, although he had a brother-in-law who lived near Surabaya and a cousin of his wife in Malang (East Java). But this was not exceptional at the time. Just before World War I broke out, the migration of European citizens to the Indies began to increase considerably. Almost all inhabitants of major cities in the Netherlands had friends or relatives in the Indies at the beginning of the twentieth century. An unquenchable curiosity for worlds unknown seems not to have been an important reason for temporarily leaving the Netherlands behind either. Aanstoots' main motivation for working in the Dutch East Indies for a few years was to make money. He saw the colony first and foremost as a 'land to get rich' and 'to build up a wonderful savings' which he could 'enjoy' back in the Netherlands. Most of the other Dutch migrants who moved to the Indies thought the same way. The vast majority of them wanted to return to their homeland in the foreseeable future. Aanstoots also wanted to prevent his family from falling into poverty if he died prematurely. The realization that his country of birth had provided him very little up to that moment, may have been the deciding factor in setting off for the tropics.

The diaries

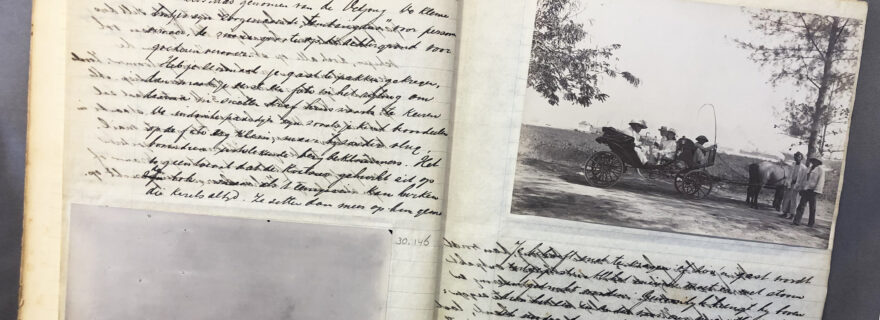

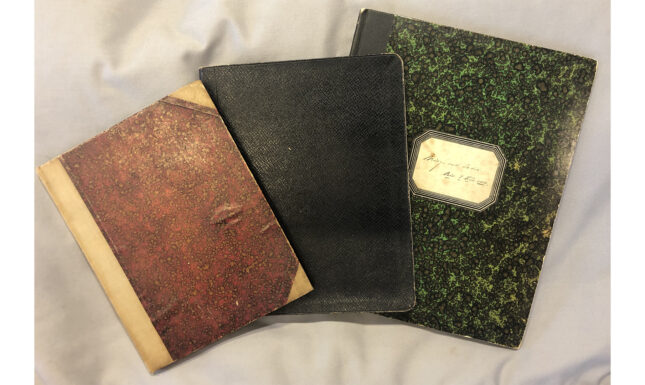

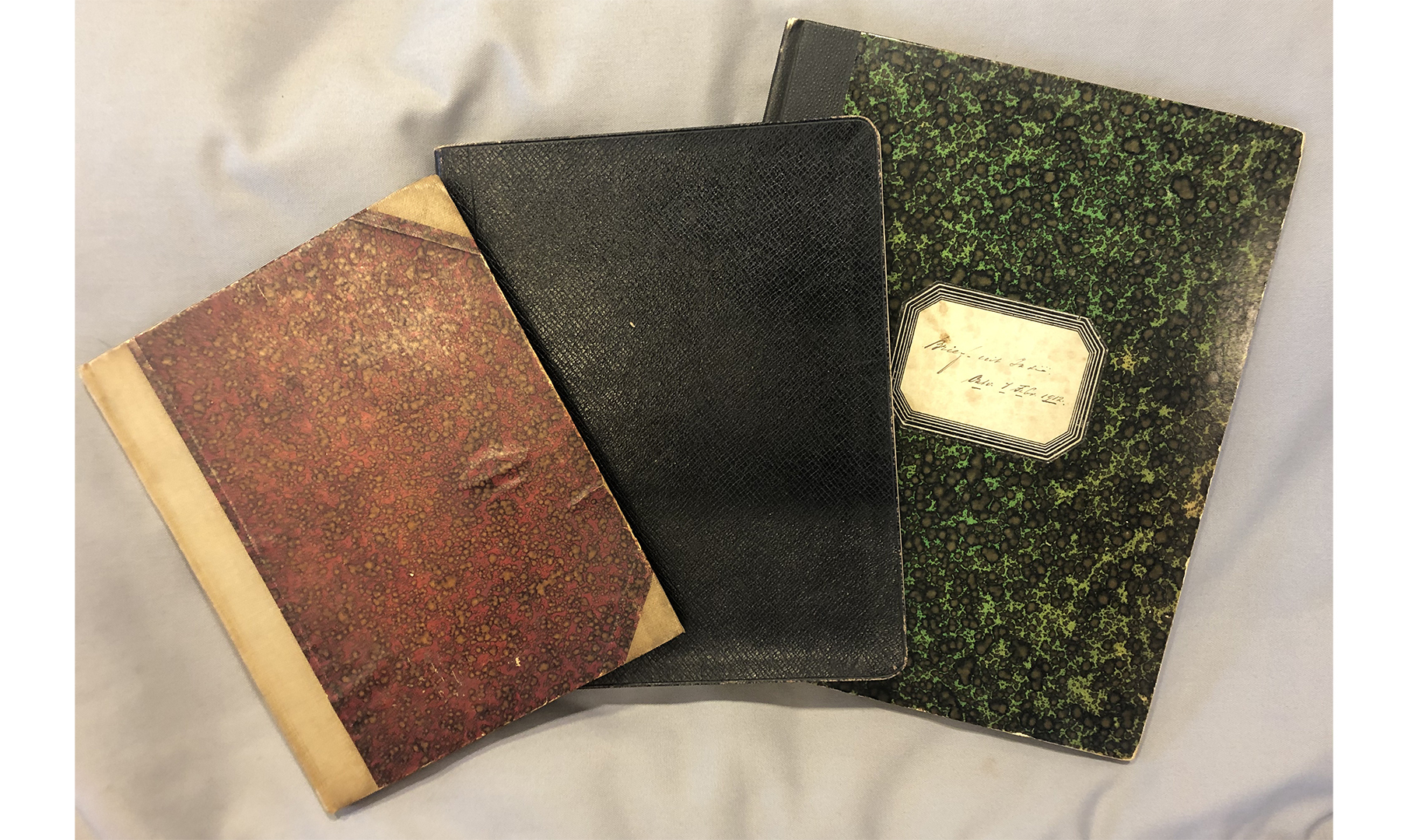

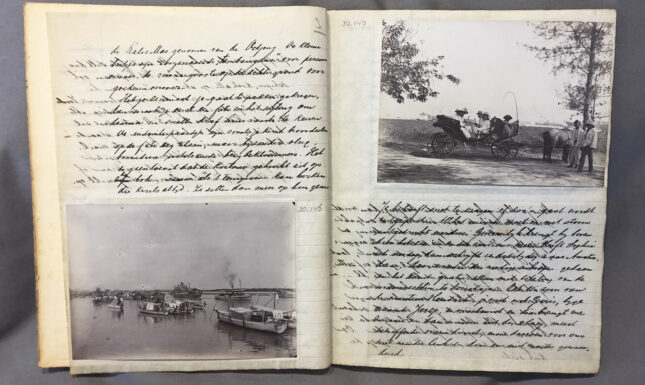

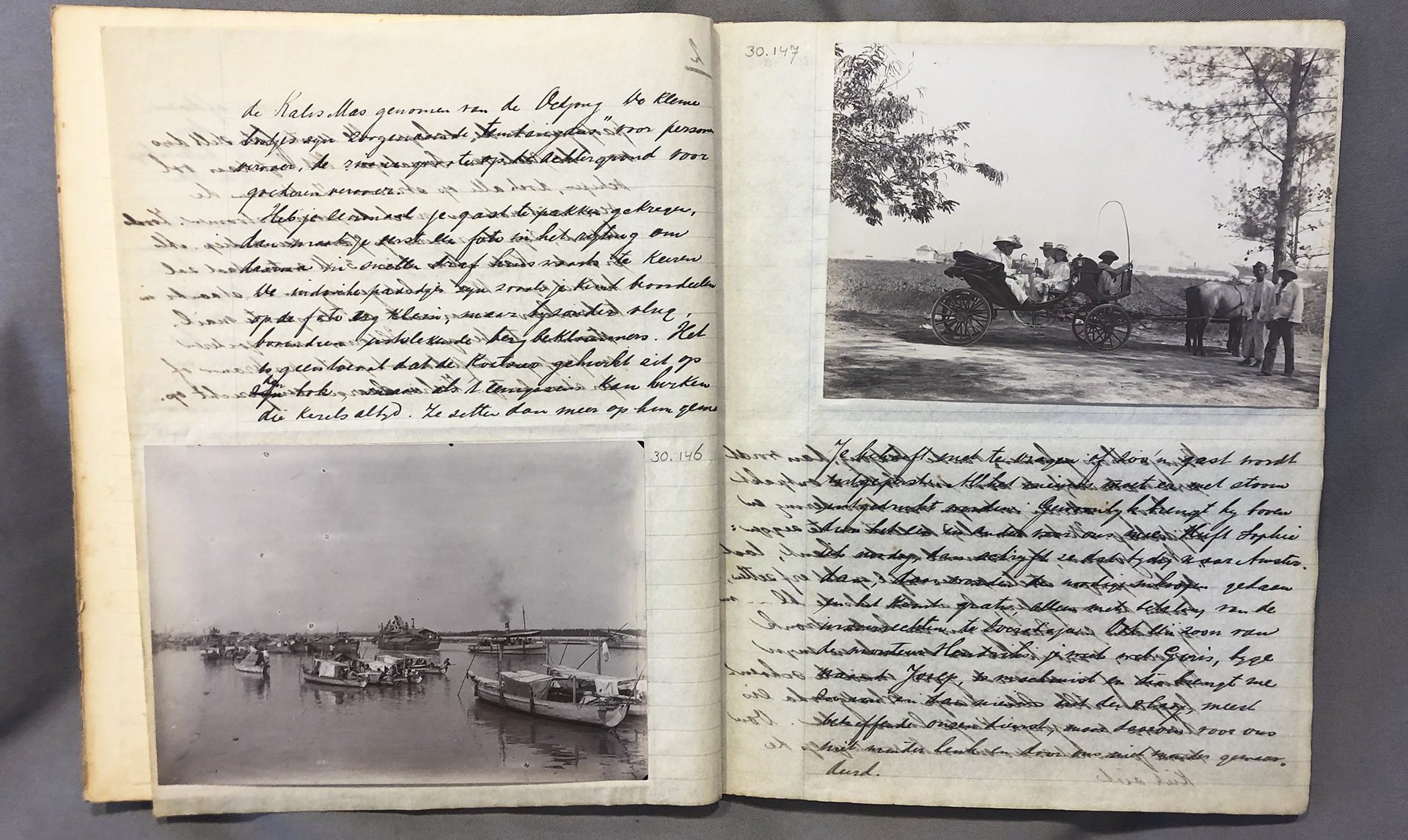

When Aanstoots left Amsterdam on the mail boat for Batavia, he started keeping a diary. In the collection of the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, which is housed in the Leiden University Libraries, there are three notebooks in which Aanstoots recounts his journey to Java and his stay in Batavia and Surabaya. They were bought in 1990 at Antiquariaat Minerva in The Hague. Together, the books comprise just over three hundred pages of writing. Unlike the first two, the third one also contains forty-one photographs taken by Aanstoots himself. Whether these are all the diary entries he made is questionable. Potentially, components have been lost.

The three booklets together form two different diaries. The first, consisting of two volumes, tells successively of the emotional farewell to friends and family, among whom were his younger brother Johan and his niece Corrie, the boat trip from Amsterdam to Batavia, and the first months in the Dutch East Indies. The period covered is almost three months: from 3 September to 20 November 1910. During the weeks on board, Aanstoots wrote about his experiences almost daily. Undisguised and with schadenfreude he recounts how hard the seasickness struck fellow passengers:

At different times, sometimes before lunch, but more often after, around two o'clock, he could spend an hour undisturbed in his imagination with his wife and child. Amidst his fellow passengers, dozing off in their deck chairs, he would catch up on his notes. He did this for himself: he could use the notes to refresh his memory now and then, but he also wrote his diary for his wife and daughter. He wanted to teach them the best way to approach their future trip to the East Indies. He also hoped that his account might make the loss a little more bearable and offer comfort until the moment Sophie would show Titi 'her father waiting on the shore'. The text also shows that Sophie Aanstoots sometimes read parts of the diary to family members in The Hague.

The second diary, consisting of one notebook, starts on 24 December 1911 and ends on 6 January 1912. This text and the photos are intended for his family in the Netherlands. His daughter and wife were with him in the East Indies at that time. Aanstoots wanted his text and photos to give his family an idea of Surabaya, the city where he and his family lived.

When interpreting this ego document, it must be taken into account that the first diary does not contain Aanstoots' original notes. He constantly sent them by mail to his wife and daughter in the Netherlands, and as far as is known they have been lost. How exactly the preserved text compares to the original therefore remains unclear. Most likely, the first diary contains a copy made by Aanstoots' wife, using her husband's notes. We can, however, state with certainty that information was lost with the disappearance of the original manuscript. For instance, the handwriting does not provide us with any information about Aanstoots' emotions. Moreover, a menu and an admission ticket, which Aanstoots, according to the text, added to his notes, are missing in any case. The third and last surviving notebook (the second diary) was probably written by Aanstoots himself. The handwriting, therefore, differs from that in the first two diaries.

Part 2

This Special Collections blog is part one of a two-part series. Part two, about the identity traits of Jacques Aanstoots that can be discerned from the diaries, has now been published.

Do you want to receive a reminder when new Special Collections Blogs are published?

Subscribe here.

___________________

Further reading

The diary of J. Aanstoots is mentioned in the Repertory of Handwritten Egodocuments of Dutch People from the Nineteenth Century, compiled by Arianne Baggerman, Rudolf Dekker, Ellen Grabowsky and Gerard Schulte Nordholt. The repertory can be consulted digitally via http://www.egodocument.net/rep.... To date, no further attention has been paid to Aantstoot's ego document by others.

For a useful introduction to the use of diaries as a primary source, see C. Hämmerle, ‘Diaries’ in: M. Dobson and B. Ziemann eds., Reading Primary Sources. The Interpretation of Texts from Nineteenth and Twentieth Century History (2nd Edition; London 2020), 160-180.

The backgrounds and fates of the Dutch emigrants who left for the Dutch East Indies in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century are outlined in Ulbe Bosma's readable study Indiëgangers. Verhalen van Nederlanders die naar Indië trokken (Amsterdam, 2010).

Nick Tomberge is a PhD student at the Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society.