The Ricklefs collection at Leiden University Libraries. Some material features.

Manuscripts are not only about content. The leather bindings, the kinds of paper, and the ink used may tell us stories without words – material talks. Dr. Dick van der Meij will introduce us to some Javanese manuscripts

In 2015, the Leiden University Libraries received a very special gift from Prof. Merle Ricklefs, who donated seven Javanese manuscripts to the library (Cod.Or. 27.087 - 27.093). Prior to this donation he had already donated the extraordinary Serat Pustakaraja (D Or. 661) to the KITLV library, now part of the UB Leiden. These eight manuscripts form a most magnificent collection on Javanese narrative traditions. However, in the following they will not be discussed for their content but for their materiality.

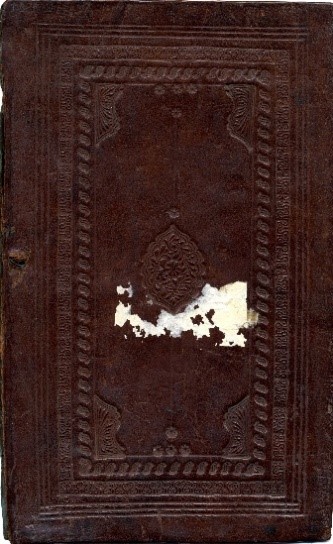

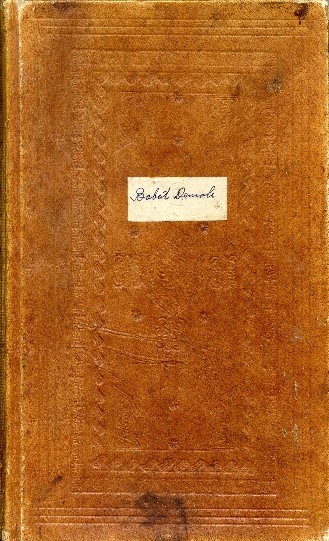

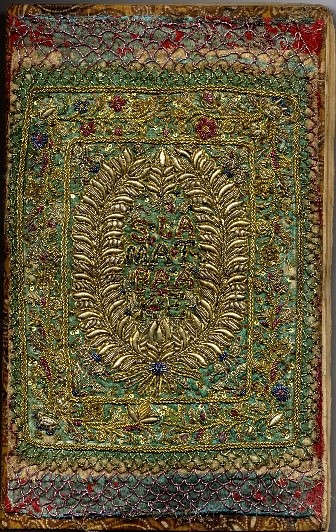

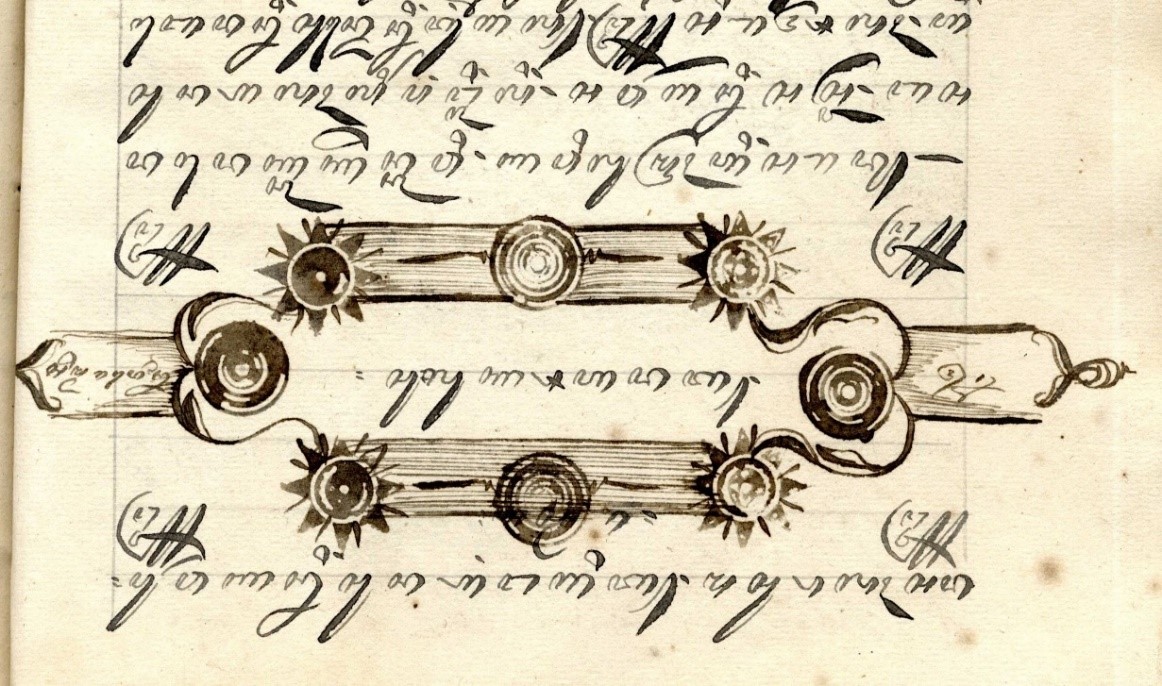

These eight manuscripts may be seen as a typical collection that was put together without any specific collecting goal except for the contents that attracted Ricklefs to buy them for his studies on Javanese history and culture. Even though small, the collection shows many of the features and material elements of Javanese manuscripts. We begin with the bindings. Manuscripts from Central Java are often bound in leather bindings that have similar stamped decorations (see illus. below, Cod.Or. 27.089 and Cod.Or. 27.092). The different binding qualities but also the use of different kinds of leather may point to particular binding makers. Cod.Or. 27.093 uses a pre-lined factory exercise book with cardboard covers, while Cod.Or. 27.087 is bound in batik (by the look of it, imported quasi-batik print made in Holland) and has a curious cover with a pattern made of cheap shiny coloured metallic thread with the words SLAMET PAAKE (enjoy using it).

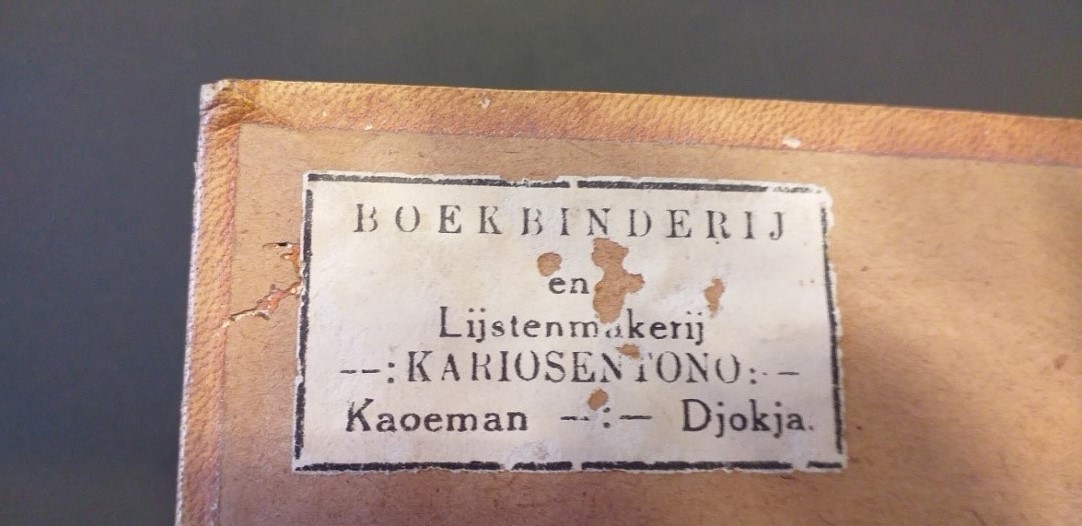

Occasionally the maker of a binding can be determined by a glued-on tag inside the cover (see below, Cod.Or. 27.092)

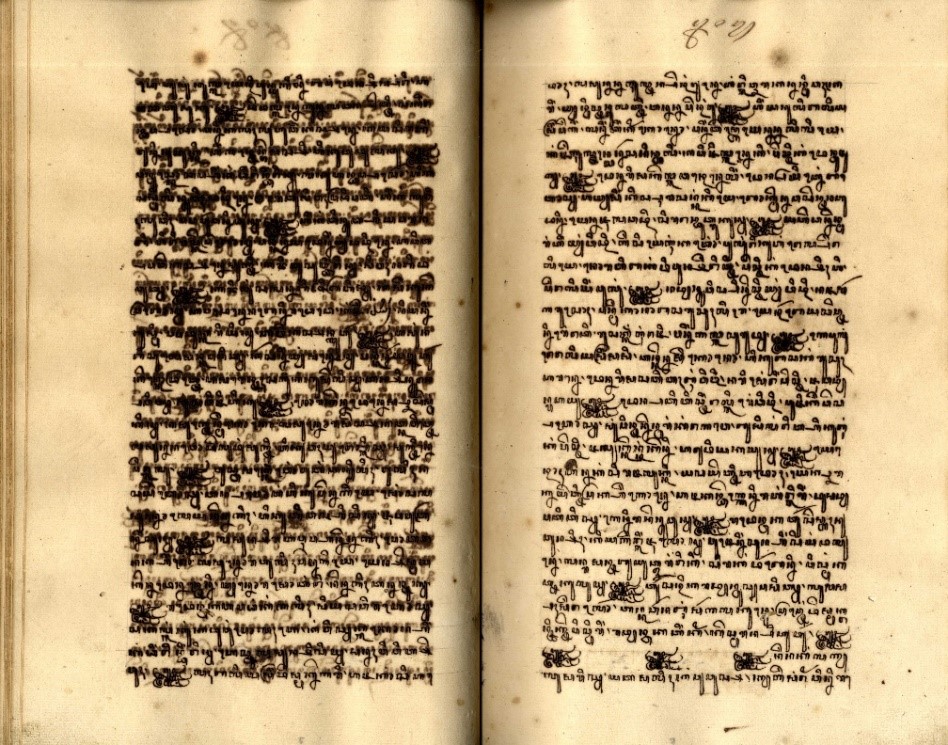

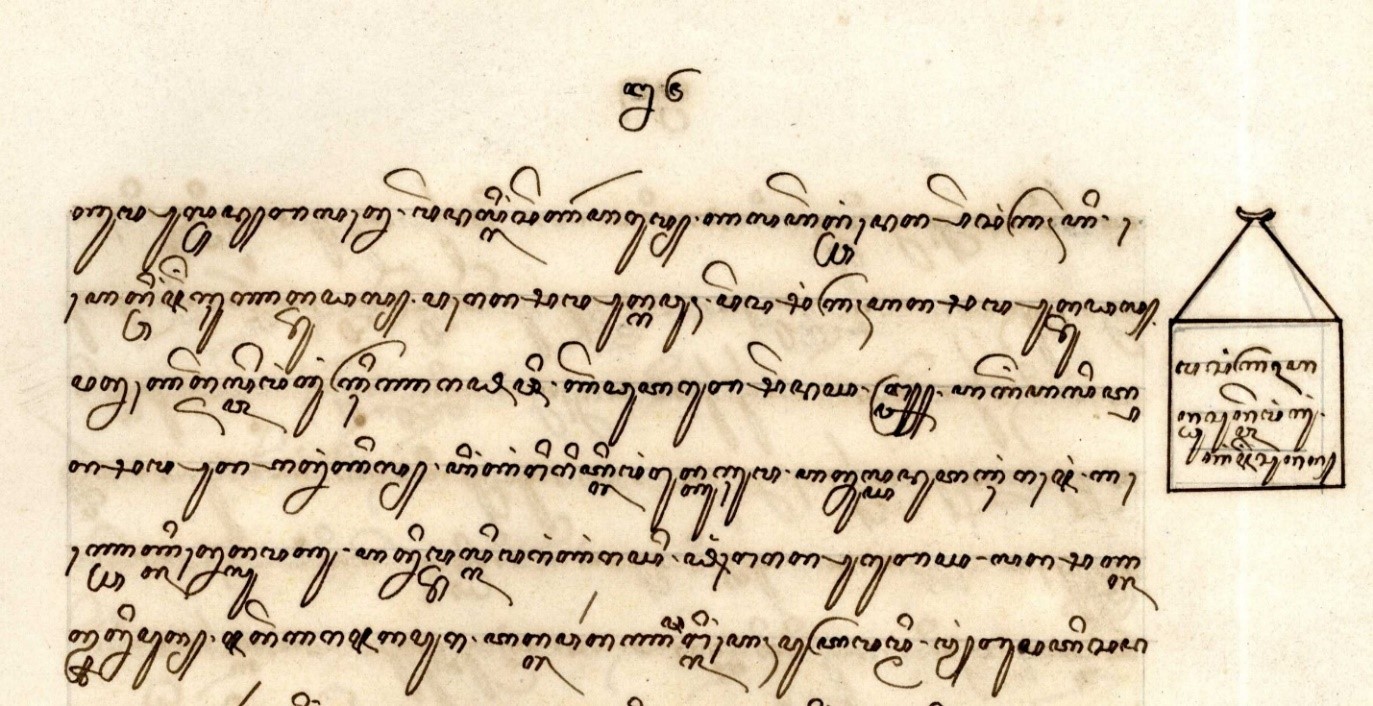

All eight manuscripts show the usual traces of use. For instance, the paper of one manuscript is partly torn and repaired with tape, while the paper of Cod.Or. 27.091 and 27.092 is seriously damaged by gall ink bleeding that has been eating its way into the paper. Strangely enough, it even occurs that one page is much more damaged than the very next (see illus. below). This could mean that a new bottle of ink was used, which possibly was of a slightly different, more paper-friendly mixture. It is striking that all these manuscripts have a distinctive smell to them, likely a combination of the paper, the ink, and the deterioration process in addition to the specific locations where they had been stored before entering Prof. Ricklefs’s collection.

Cod.Or. 27.092. Folio 203 is seriously damaged by iron gall ink bleeding, while the next folio 204 has nowhere near the same problem.

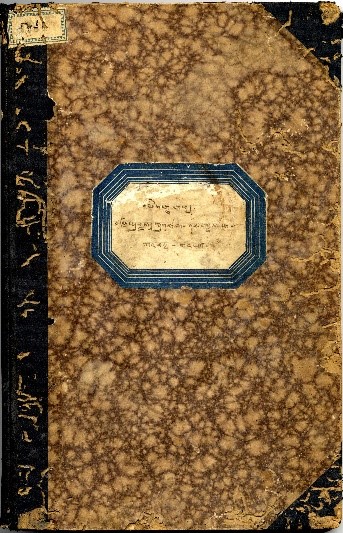

The manuscripts were all produced in Central Java. They are written in various styles of Javanese script as used in the Central Javanese courts and cultural surroundings. The paper used for these manuscripts is partly ordinary paper, and partly high-quality paper as used among Central Javanese high society members. Seven of the manuscripts contain texts on the history of Central Java (called babad, also spelled babat). The manuscript of the Pustakaraja (D Or 661) is of particular interest as it is the oldest manuscript of this text now known. One manuscript contains a collection of mystical short poems (suluk, Cod.Or. 27.087) preceded by the Kidung Rumeksa ing Wengi (Song Guarding the Night). All the manuscripts were written in non-rhyming Javanese verse (called tembang macapat) in a large number of poetic metres. Each text has a number of subdivisions in the same metre called canto.

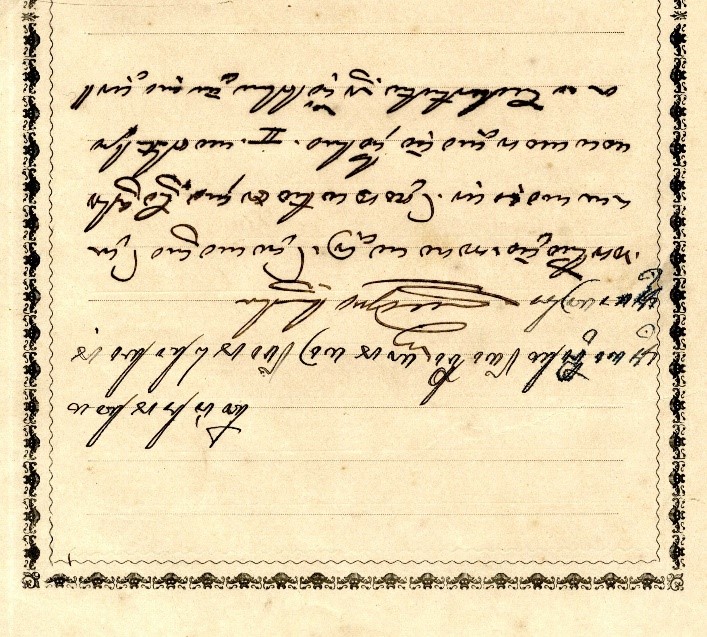

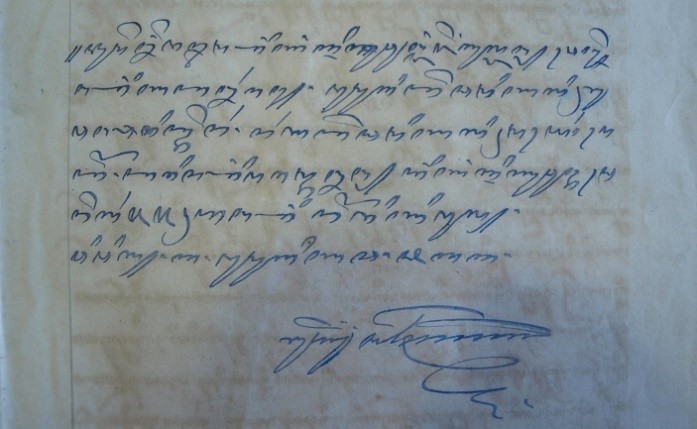

All eight manuscripts start with the expected information stating when the manuscript was written, but not by whom. Information about ownership and dates of production and short synopses of contents may be found on separate pages that precede the text proper. As illustrated below, this information sometimes ends with a signature that is usually hard to read, as any signature in whatever writing system. However, even illegible signatures can help us to decide if manuscripts stems from the same collection, for instance Cod.Or. 27.089 and Cod.Or. 27.090 that clearly share the same- illegible - signature. A legible signature is found in Cod.Or. 27.093, Babad Prayut. It is stated that the manuscript was written by Sumahatmaka on 9 August 1932.

Left: Cod.Or. 27.090 Babat Sinuwun Jeng Sultan ing Ngayugya Sapisan. Note preceding the text proper.

Right: Cod.Or. 27.089 Babad Metaram. Note preceding the text proper.

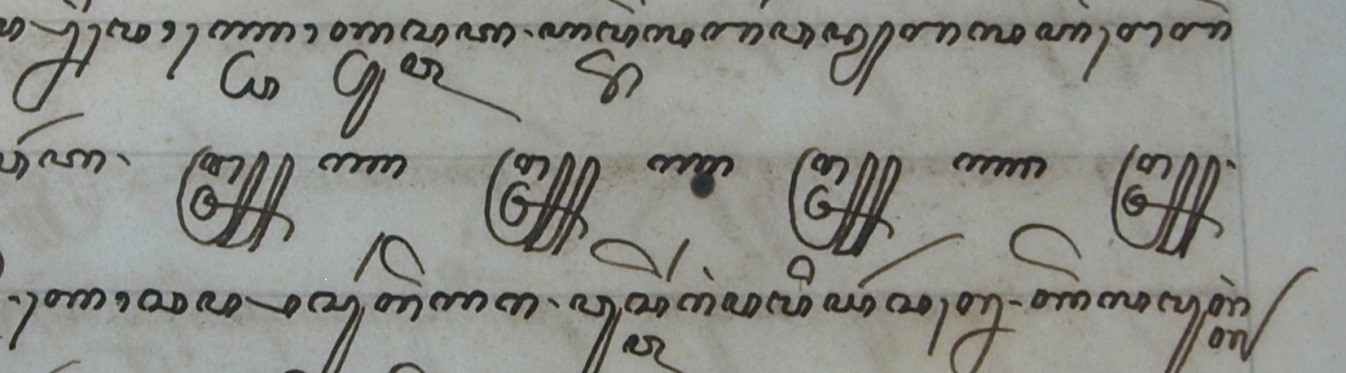

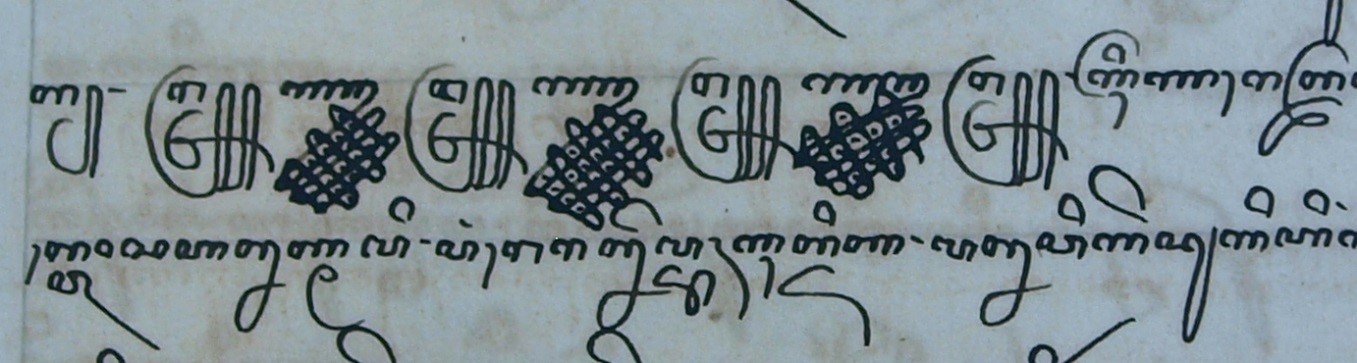

Manuscripts often have more than just one creator. Cod.Or. 27.089, for instance, was written in no less than three hands, which becomes especially clear when we take a closer look at the indications that show where one canto of the verse ends and a new one starts:

Cod.Or. 27.089 Babad Metaram, p. 24

Cod.Or. 27.089 Babad Metaram, p. 278

Cod.Or. 27.089 Babad Metaram, p. 518

Babad Metaram: Three different pepadan indicating that the manuscript is the work of three different scribes.

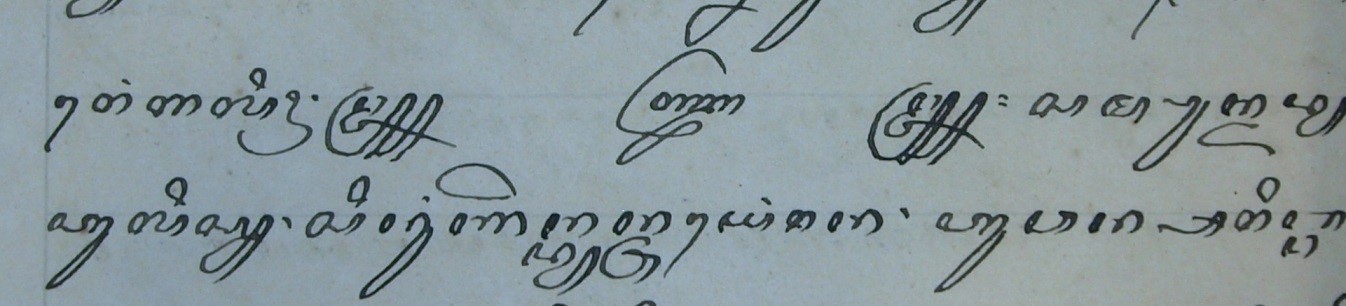

Javanese manuscripts do not use chapters or chapter headings as we know them in Western manuscripts. Looking at the pages, one may wonder how people are able to easily find their way in these manuscripts. Routine readers of course know their tricks. In the first place, we see that the canto indications differ, and indeed, no two are exactly the same. That can help readers to remember where they want to pick up reading: by remembering what the pepadan looked like at the start of the particular canto, or where it was located (in the centre of the page, at the top or bottom, or somewhere at the side). More rarely, manuscript producers (or perhaps users after them) numbered the cantos, as is, for instance, the case with Cod.Or. 27.087. Here, not only the title of each song (suluk) is stated but also often the name of poetic metre in which it is written and the number of the text within the manuscript.

Cod.Or. 27.087. Indication that the new text is the Suluk Sahadat (in the centre, that the verse form is Asmarandana, at the far left and that it is the 52nd text in the collection at the far right.

Other marginal marks to indicate where an important part of the text starts can be seen below. Interestingly, in both instances the effort to provide these indications was abandoned after just a few pages whereas in the rest of the bulky manuscripts no further indications were made.

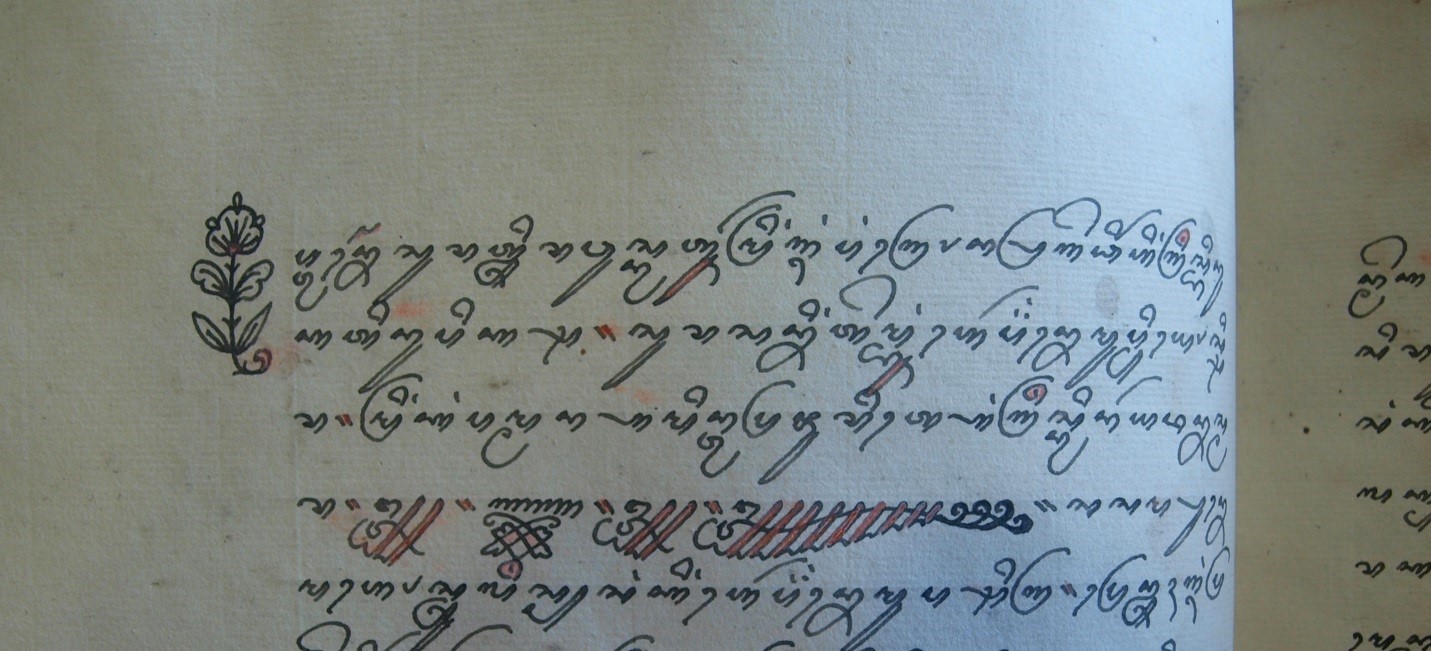

Cod.Or. 27.089. Manuscript with a short indication of the contents of the part of the text it accompanies.

Cod.Or. 27.089. A flower on the left shows that the text is important. The indication of the new verse form below does not seem to have any relation with the flower as other flowers in the manuscript also do not correspond with the start of a new canto.

Conclusion

Not only do the manuscripts that Ricklefs donated to Leiden convey intriguing text, they also display many of the features codicologists should look at, when they wish to understand the text transmission of the Javanese. Linking information from different manuscripts may offer clues as to what the dynamics of this transmission was and help us to understand the role of manuscripts and manuscript producers in society.

The Ricklefs collection:

Cod.Or. 27.087 Kidung Rumeksa ing Wengi and Collection of Suluk, AD 1860s

Cod.Or. 27.088 Babad Kartasura, AD 1860

Cod.Or. 27.089 Babad Metaram, AD 1885

Cod.Or. 27.090 Babat Sinuwun Jeng Sultan ing Ngayugya Sapisan, AD 1905

Cod.Or. 27.091 Babad Majapahit Pungkasan Dumugi Mataram, vol. I, AD 1853 ?

Cod.Or. 27.092 Babad Majapahit Pungkasan Dumugi Mataram, Babad Demak vol. II, AD 1853 ?

Cod.Or. 27.093 Babad Prayuat, AD 1932

KITLV Or. D 661 Pustakaraja, AD 1850s ?

Author: Dr. Dick van der Meij is a Visiting Professor at the State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, Indonesia and a former lecturer for Indonesian Literatures at Leiden University.

Donor: Professor M.C. Ricklefs recently retired from the Professorship of Southeast Asian history at the National University of Singapore and is currently Emeritus Professor of History at both the Australian National University and Monash University. His study of the cultural, political and colonial history of Indonesia, with Central Java as a focal point, yielded standard works like A History of Modern Indonesia, ca. 1300 to the present. Leiden University Library is grateful for his donation of the unique manuscripts discussed above.