The Esperanto textbooks that never were

Among the many joys of doing research, my favourite is best described as “archival serendipity”. When my research kept yielding correspondence in Esperanto I decided to have a look in the Leiden Special Collections. The result: Or. 6767: a complete grammar of Tibetan, explained in Esperanto.

Among the many joys of doing research, my favourite is best described as “archival serendipity” – to find something you were not actually looking for. Few things are more attractive than pulling on a thread you never knew was there, just to see what might unravel. This is one of the reasons I tend to get particularly excited when the Special Collections catalogue describes an item as [place of production not identified]: [producer not identified], and [date of production unknown].

Most of the archives for my current research tend to be further afield, but I have long ago learned to never bypass Special Collections: you never know what they might hold. So, this time, when my research kept yielding international correspondence in Esperanto in an unlikely timeframe (1960s) and among a less than obvious community (Indian socialists), I decided to have a look. Might anything in the Special Collections connect India to modern Esperantists? It was a long shot, and I was as surprised as anyone when the catalogue gave me Oriental Manuscript 6767: Kompleta Gramatiko de la Tibeta Lingvo klarigita en Esperanto: a complete grammar of Tibetan, explained in Esperanto.

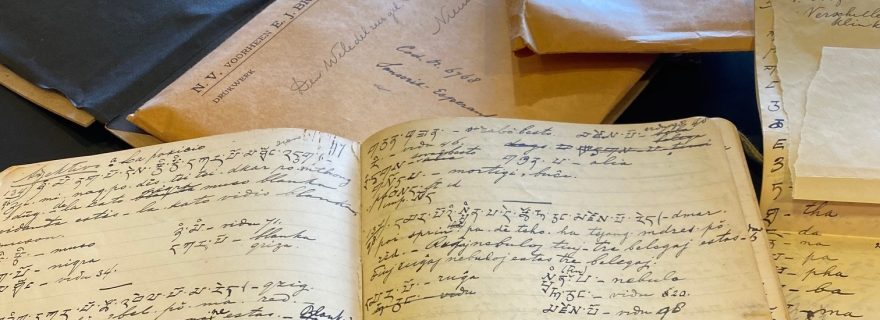

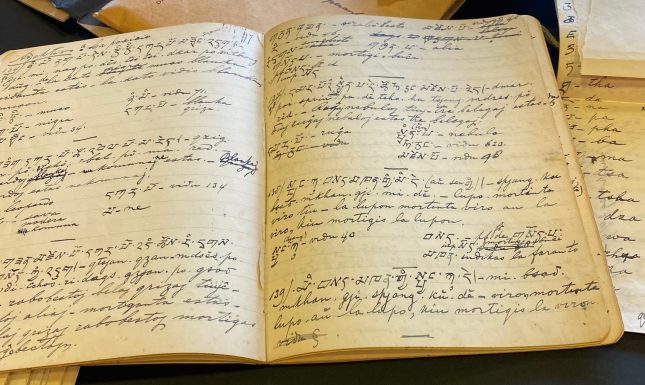

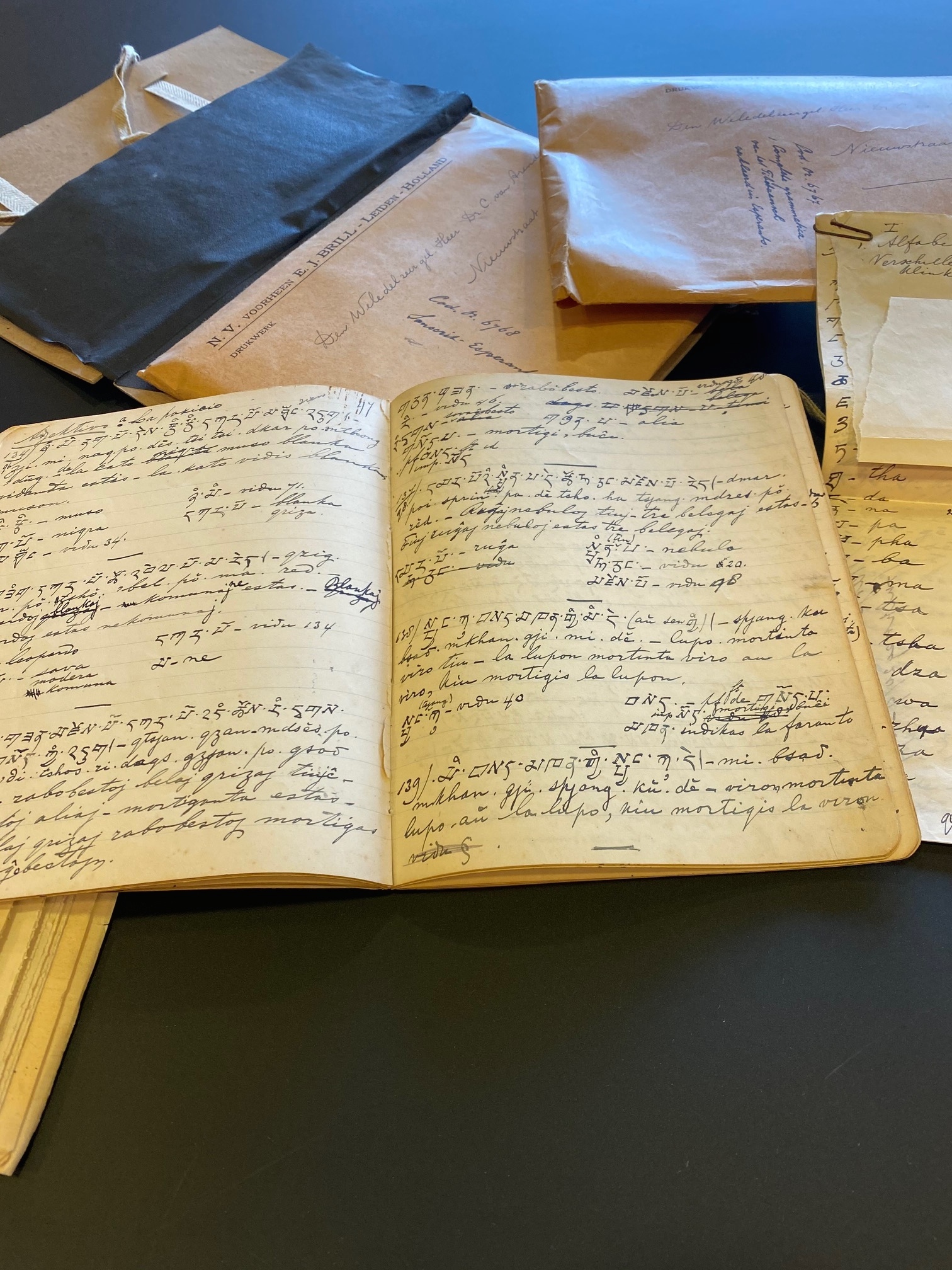

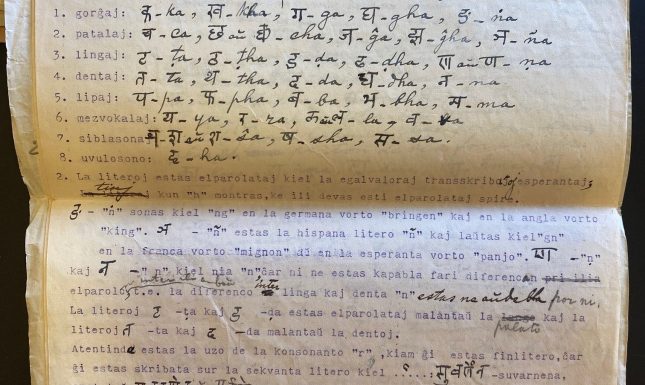

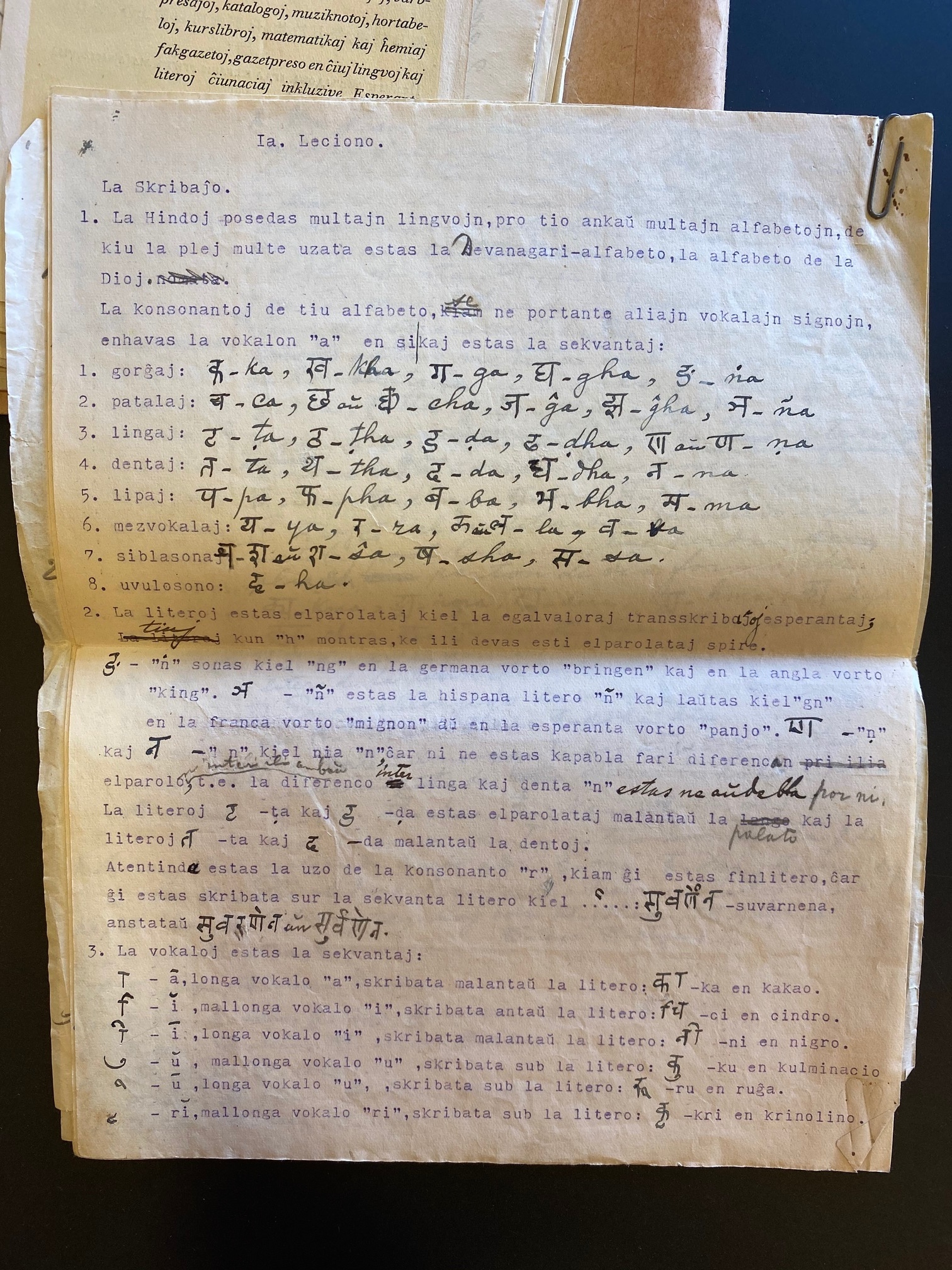

Resting in two large envelopes from Brill Publishers was a labour of love. Oriental Manuscript 6767 is, in fact, two manuscripts. One a grammar of Tibetan, with the alphabet, syntax, and linguistic idiosyncrasies painstakingly explained in Esperanto; the other a grammar in which Sanskrit had been given the same treatment. Both grammars are extensive and methodical. Sadly, the envelopes offer no context, but both the author of the manuscripts and the person to whom Brill forwarded them are listed and offer some insight into how these documents came to rest in Special Collections.

First, the author. P.W. van den Broek was a Dutch colonial official on Java. He held various posts throughout his career, which culminated in his becoming “assistant-resident”, the highest official in a regional subdivision. He was also a founding member of the Nederlandsch-Indische Esperantisten-Vereeniging (Dutch East Indies Esperantist Association). As Heidi Goes notes, Van den Broek even directed a course in Esperanto through the Association’s journal Neratja under the pseudonym Esperantist in the 1920s. Evidently, when he retired from the colonial civil service, he continued his mission of spreading Esperanto and produced these textbooks for Tibetan and Sanskrit.

The obvious question one might ask is, how far-fetched was this project? From a contemporary perspective, a textbook like this would seem to limit the – already limited – potential audience for Tibetan and Sanskrit even further. Seen from the interwar years, however, textbooks like these would do the exact opposite: they would remove the need for separate textbooks opening a given language to every learner’s native tongue. Especially in the arts and sciences, Esperanto had many committed adherents. Before the widespread acceptance of English as the medium of international academic communication, experimental conferences conducted entirely in Esperanto were enthusiastically heralded as “eliminating the need for translators”. Again, Special Collections offers insight here, as KITLV DH 1326 contains letters from the “Dutch Association for the application of Esperanto in the Arts and Sciences” from the 1940s, singing the praises of the various ways in which Esperanto was internationalising academe.

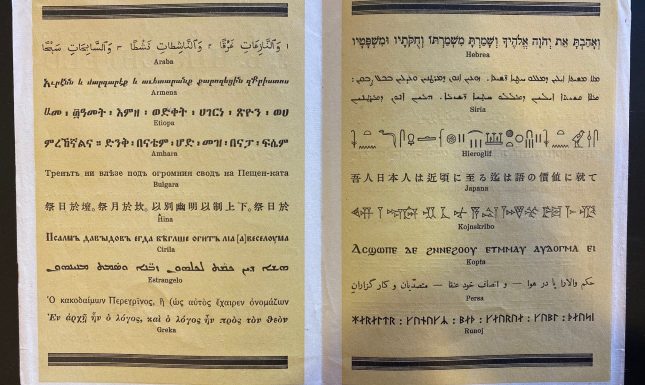

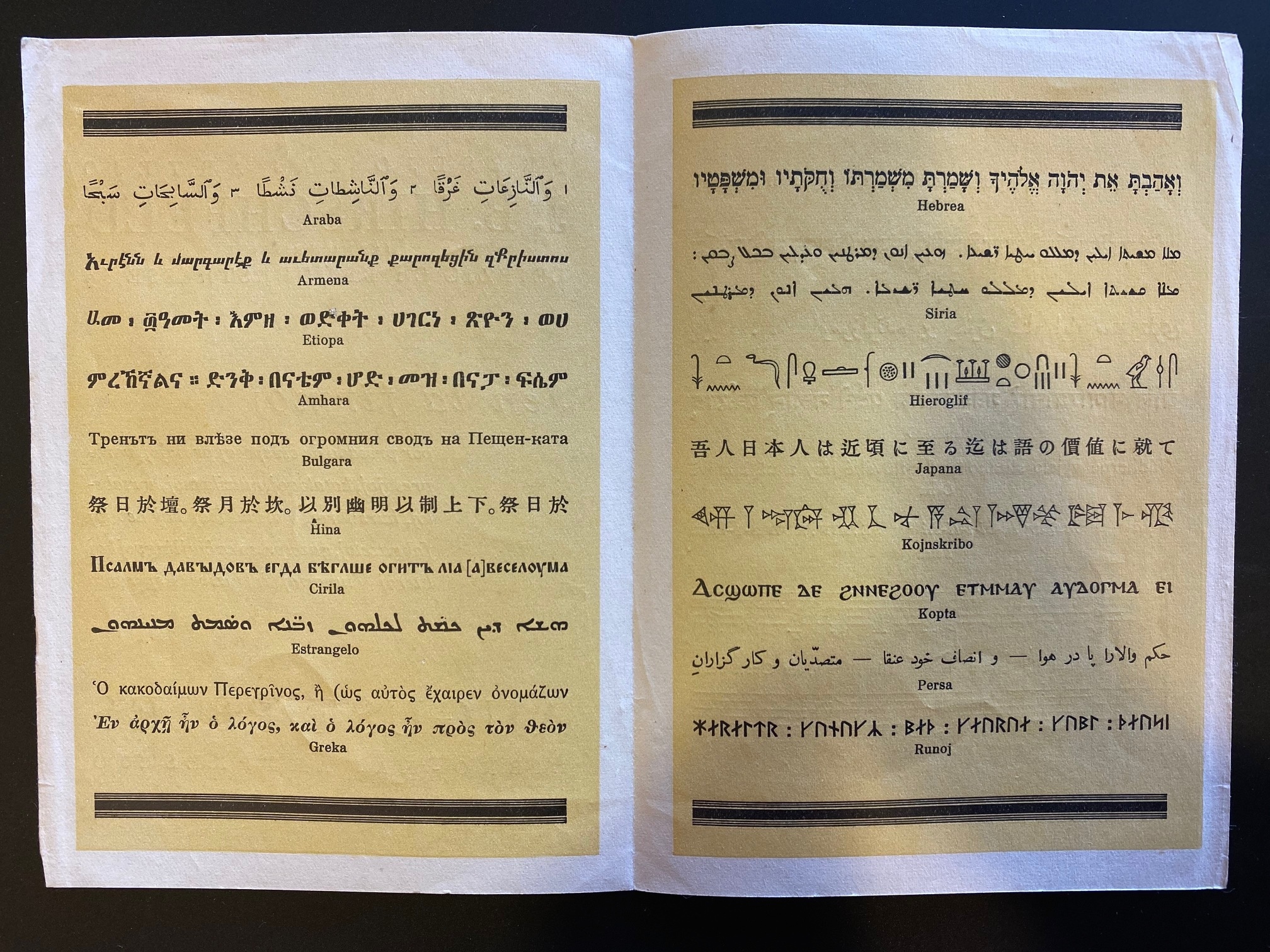

If P.W. van den Broek was convinced of the need for his textbooks, Brill was clearly not dismissive of it either. Enclosed in the envelopes is a flyer for a publishing house in Leipzig, entirely in Esperanto, announcing the many alphabets that they were able to print. Clearly, there was precedent. The texts themselves, however, would have to be vetted by an expert first. That expert, judging from the envelopes, was Cornelis van Arendonk. Cornelis van Arendonk had studied Arabic under Snouck Hurgronje and went on to write a PhD in early Arab history. Having developed much-praised linguistic and philological expertise, he was appointed adjutor Interpretis Legati Warneriani, a position tied to curating the collection’s Oriental Manuscripts.

The manuscripts, however, never left Van Arendonk’s desk at the library, which is likely why they reside there still today. We can only guess as to the reasons why. Did Van Arendonk deem the manuscripts unworthy of publication? His obituary in the yearbook of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), of which he was a member, dwells at some length on the thoroughness he demanded of others and of himself. The opposite, however, seems equally likely: that he found the project fascinating. This appears to have characterized much of Van Arendonk’s professional life. His expertise and willingness to prepare critical editions of texts made him a sought after specialist, but colleagues “feared to ask his help, knowing that they would unleash a spirit of helpfulness that was impossible to control, much like those in One Thousand and One Nights.” Few of the texts he worked on ever appeared in print, and one cannot help but wonder if Van den Broek’s elegant Esperanto renderings of Sanskrit and Tibetan are among them.

Carolien Stolte is an Assistant Professor of History at the Leiden University Institute for History.