The elusive Panji pops up in Leiden

Who is Panji, and what exactly is a Panji tale?

Recently, on 21 September 2018, a special symposium was organised by the Leiden University Library and the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV) to celebrate the Unesco-Memory of the World recognition of the Panji stories in manuscripts in Leiden University Library as well as in libraries in Indonesia and mainland Southeast Asia.

To this day the adventures of Panji, prince of an ancient kingdom in East Java (Jenggala), remain immensely popular in Indonesia, especially in Java and Bali - yet it is not easy to say who is Panji, and what exactly is a Panji tale. Starting in colonial times, many scholarly studies have been written about the meaning of Panji stories, their historical and cultural value for the peoples of Indonesia, and the world at large. While the majority of these studies concern literary versions of Panji stories, more recent research also investigates the depictions of Panji tales on temple-reliefs, in paintings on scrolls or cloth, and in drawings. But in spite of all these scholarly investigations, it remains hard to define what all Panji stories have in common. Is there indeed an "essential Panji story", and if so, in which form?

One of my first encounters with a Panji story was in a small village south of Yogyakarta, where, as a young student of Javanese theatre and dance, I saw a troupe of local masked actors perform a play entitled: "Galuh Candra Kirana Murca", "the disappearance of Candra Kirana" - one of the names of Panji's spouse. On that sultry tropical night, during the agricultural village ritual of "bersih desa", I was seated as a guest besides a wobbly bamboo stage that had been constructed next to the village hall, its yard crowded with eagerly waiting villagers.

After a lively introduction by the local gamelan orchestra, the play opened with a deliberation between the king and his councillor, interrupted by the entrance of a number of masked actors, some of them wild demons eager to fight. As the night grew darker, the sudden appearance of a tall, red-faced ruler sent shivers through the crowd of men, women and children. Unfortunately, by midnight my host urged me to come home, before I had even seen a glimpse of Candra Kirana, the heroine of the play.

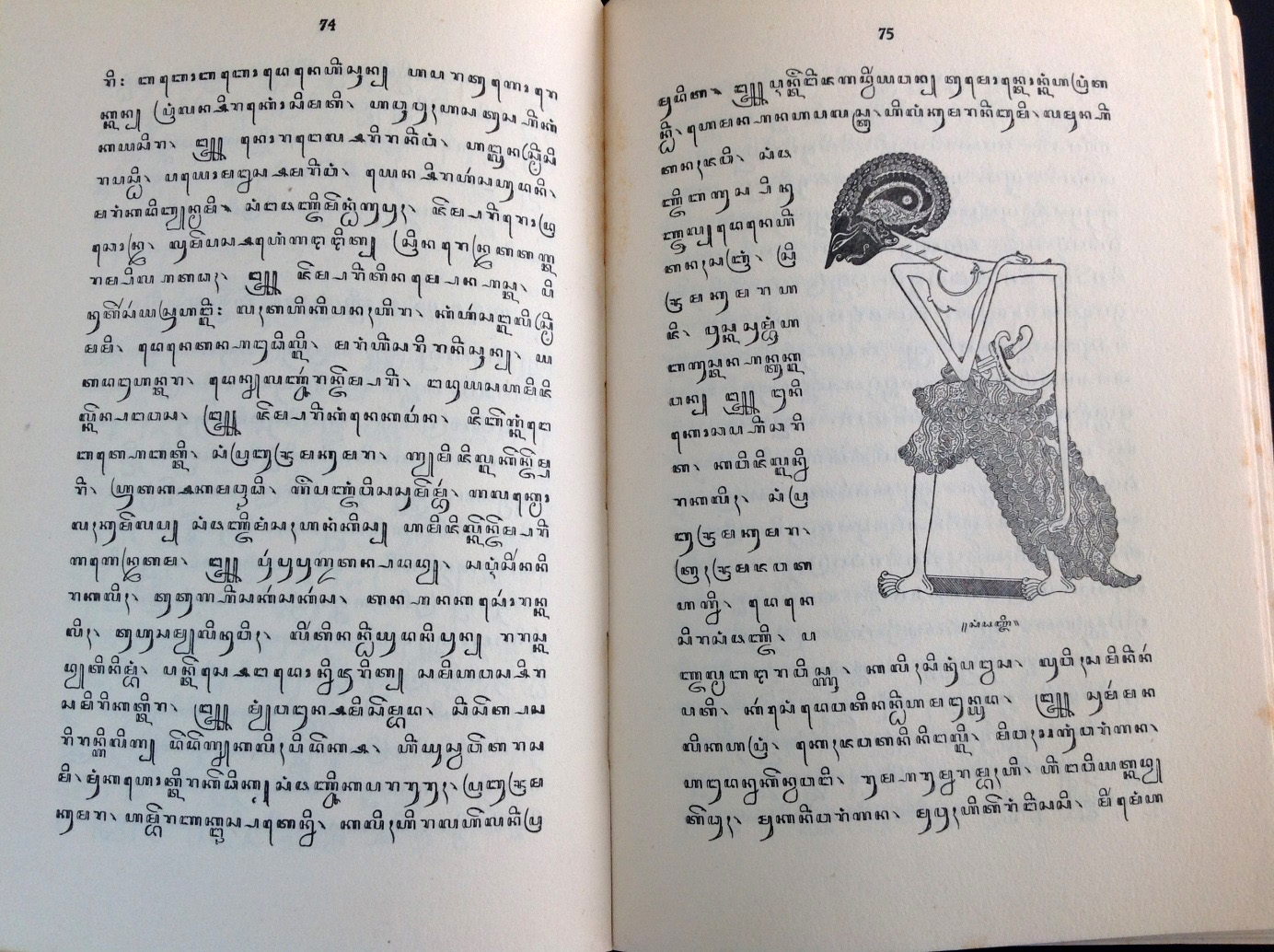

Illustration 1. KITLV3 Mii 587 Panji sekar

KITLV3 Mii 587, Panji Sekar, a Panji story in verse composed by Sunan Paku Buwono IV, published by Bale Poestaka, Betawi Centrum, 1933. The illustration on p. 75 depicts Sang Panji in the form of a wayang puppet of a young nobleman, in a sad mood.

Determined to find out more about that fascinating, unfinished play, once I was back in Leiden I started looking for Panji stories in the collections of manuscripts and printed books in the University Library and the KITLV.

As according to the script princess Candra Kirana was transformed into a man named "Kuda Narawangsa", I tried to find Javanese texts mentioning that event. And indeed, I came across several texts of the Kuda Narawangsa story featuring, as usual, the separation and final re-union of Panji Asmara Bangun and his spouse Candra Kirana, also named Sekartaji.

Apart from the confusion caused by the transformation of the main character, much upheaval was created by an intruding foreign ruler with his bands of demons, as I had witnessed. But in the end, after a series of battles, Panji managed to overcome all problems in an ultimate confrontation with his enemy: the fierce Klana and his demonic followers. They were defeated and his beloved princess Candra Kirana returned to Panji in her original shape.

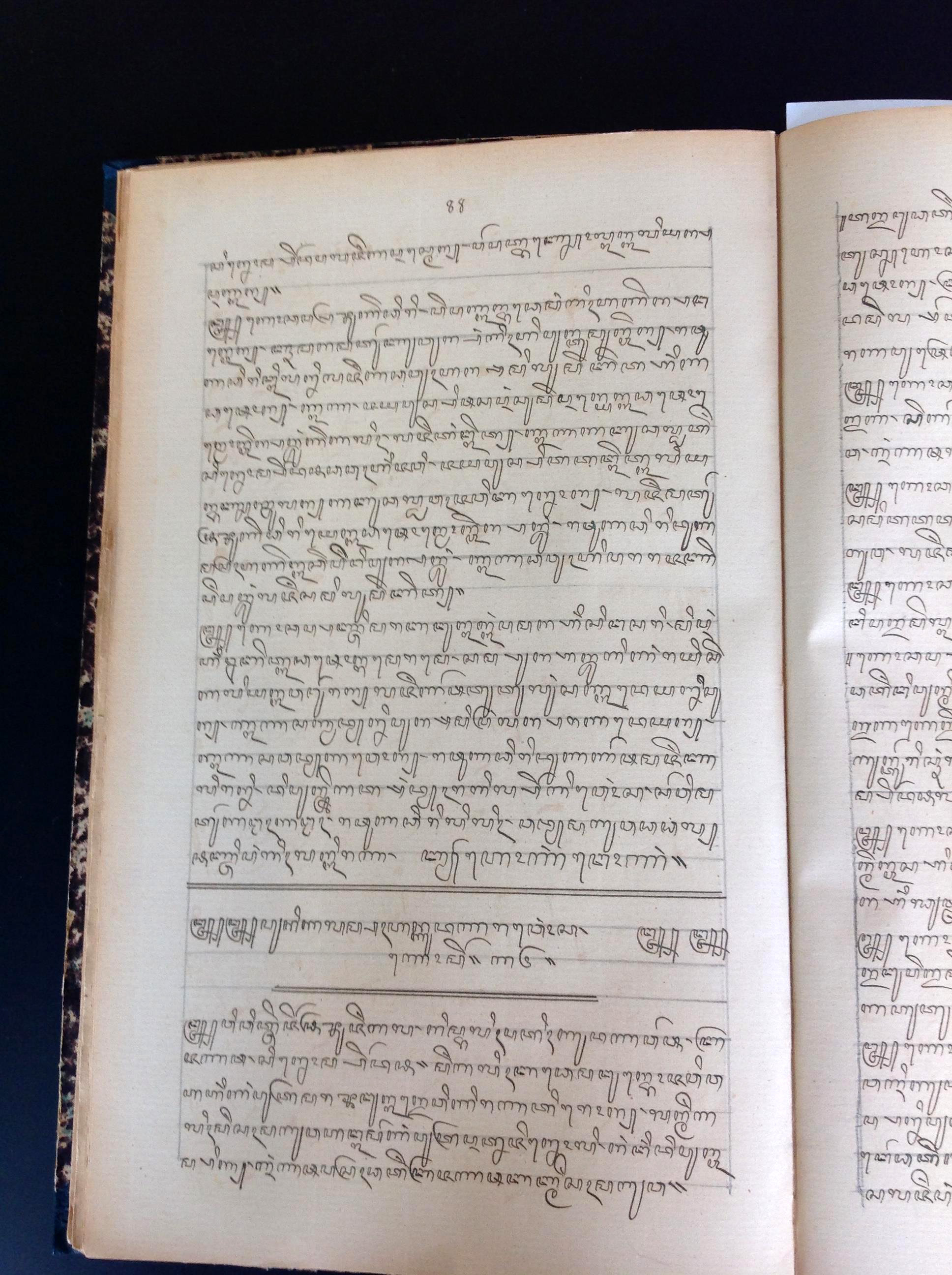

Illustration 2. Or 6428 Serat pakem ringgit gedhog

Or 6428, Serat pakem ringgit gedhog, p. 88, the beginning of lakon Kuda Narawangsa.

Not only did I find evidence of the Kuda Narawangsa story in literary works and articles, there were also theatrical versions to be found in collections of Javanese play-scripts (pakem) from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, written by noblemen or court-artists. One of these, Or 6428, entitled Serat pakem balungan lampahanipun ringgit gedhog, contains 51 outlines of puppet plays (wayang gedhog), written down by Mas Ngabehi Wangsadipoera for the Chancellor of the Sultan of Yogyakarta (collection dr. G. A. J. Hazeu).

Illustration 3. KITLV 3932, Cephas photograph

KITLV 3932, Cephas photograph, Panji scene by masked actors in Yogyakarta, 1888.

Moreover, among the historical photographs kept in the collections of the KITLV there were four photographs of Panji performances made by the well-known Javanese photographer Cephas, showing masked actors posing at the court of Yogyakarta in 1888.

All this proves that the Kuda Narawangsa story was a well-known topic of theatre plays during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Java. Again, each play represents a different version of the story, with much variation in detail of the action as well as interaction between various characters. So far, I have not found one single, original version of the story, and no identical copies either.

Illustration 4 - 5. Wayang jantur practice by Ki Agus Bimo Prayitno in Leiden

At the end of a day full of discussions on various aspects of Panji stories in manuscripts, paintings and performance, the Leiden symposium ended with a spectacular "wayang jantur" performance by the Javanese puppeteer Ki Agus Bimo Prayitno and his group, singer Paramitha Santosa Putri, musicians Darwita, Adya Satria Handoko Warih, and organiser Lydia Kieven. In their play entitled: "Kidung Panji Biyung Bibi" (Biyung Bibi is a local name for the active volcano Mount Merapi, near the town of Yogyakarta) we experienced yet another transformation of this well-known hero: during a moving central scene the noble Panji was turned into a simple village youth. In this form, Panji was able to offer advice to the many villagers in Java who are presently experiencing great environmental troubles, such as volcanic eruptions, drought and earthquakes, that are threatening their very existence.

Wayang jantur scene with Panji as a nobleman (right) accompanied by a servant. Practise of dhalang Ki Agus Bimo Prayitno, Leiden 20 September 2018. Photographer: Bernard Kleikamp

Accompanied by the small musical ensemble, the puppeteer's clear, beautiful storyteller's voice convinced our Leiden symposium-audience that the lasting popularity of these Panji tales derives from their ability to transform, to adapt continuously to changing circumstances.

Wayang jantur performance by Ki Agus Bimo Prayitno, scene of Panji in the village, Leiden 21 September 2018. Photographer: Bernard Kleikamp.

Post by Clara Brakel.