The Confusion of Cyrillic Script

For a long time no one in Leiden knew very well how to deal with books from Eastern Europe. A Croatian translation of the New Testament was taken for Russian until the eighteenth century.

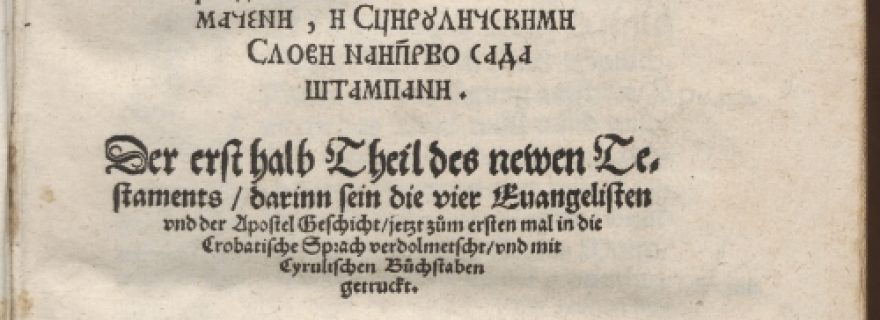

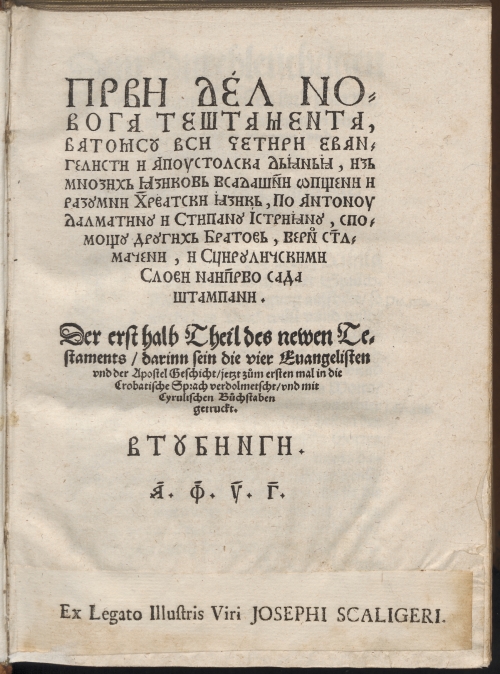

Apparently the confusion had arisen because the book was printed in Cyrillic script and because the title had not been read or understood correctly. Yet it is perfectly clear from the titlepage that it is an edition ‘in die Crobatische Sprach verdolmetscht’ (‘translated into Croatian’).

The Croatian translation of the New Testament was produced by two protestant reformers, Stephanus Consul from Istria and Antonius Dalmata. The book was printed in two editions, one in Cyrillic script and one in Glagolitic (Old Slavic). Presumably these two editions were to help disseminate Protestantism among the Roman Catholic Slavic peoples in Southern Europe. These expressly included the Christians living in regions under Turkish rule. The book was printed in Urach near Tübingen at the residence of the Protestant Count Hans III Ungnad from Styria (Austria), who financed the whole operation. Eventually some 25 Bibles, catechisms and hymn books were published, both in Slovenian and Croatian.

The copy in Cyrillic script in the Leiden University Libraries hails from the library of the jurist Simon Clüver from Gdańsk, the great-uncle of the humanist Philippus Cluverius (1580 – Leiden 1622/23). Philippus Cluverius served for a while at the court of the King of Poland, but then left for Leiden to read Law. He subsequently turned towards the history of geography at the advice of Joseph Justus Scaliger. From 1607 to 1613 Cluverius travelled extensively across Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Western Europe (England, France and Italy), which enabled him to learn several modern languages. In 1616 Cluverius was appointed Geographus academicus at the University of Leiden. Cluverius is generally regarded as the founder of historical geography. In this capacity he combined an impressive classical erudition with a sense for fieldwork and critical empirical acumen.

Collection Leiden University Libraries (1365 F 14)

It is very likely that Cluverius gave the book to Scaliger when he arrived in Leiden in 1601. Cluverius must have realised that his great-uncle’s heirloom would make an excellent gift for Scaliger, who was deeply involved in the study of exotic languages.