Tears behind a manuscript - The tragic history of a Dutch East Indies’ officer

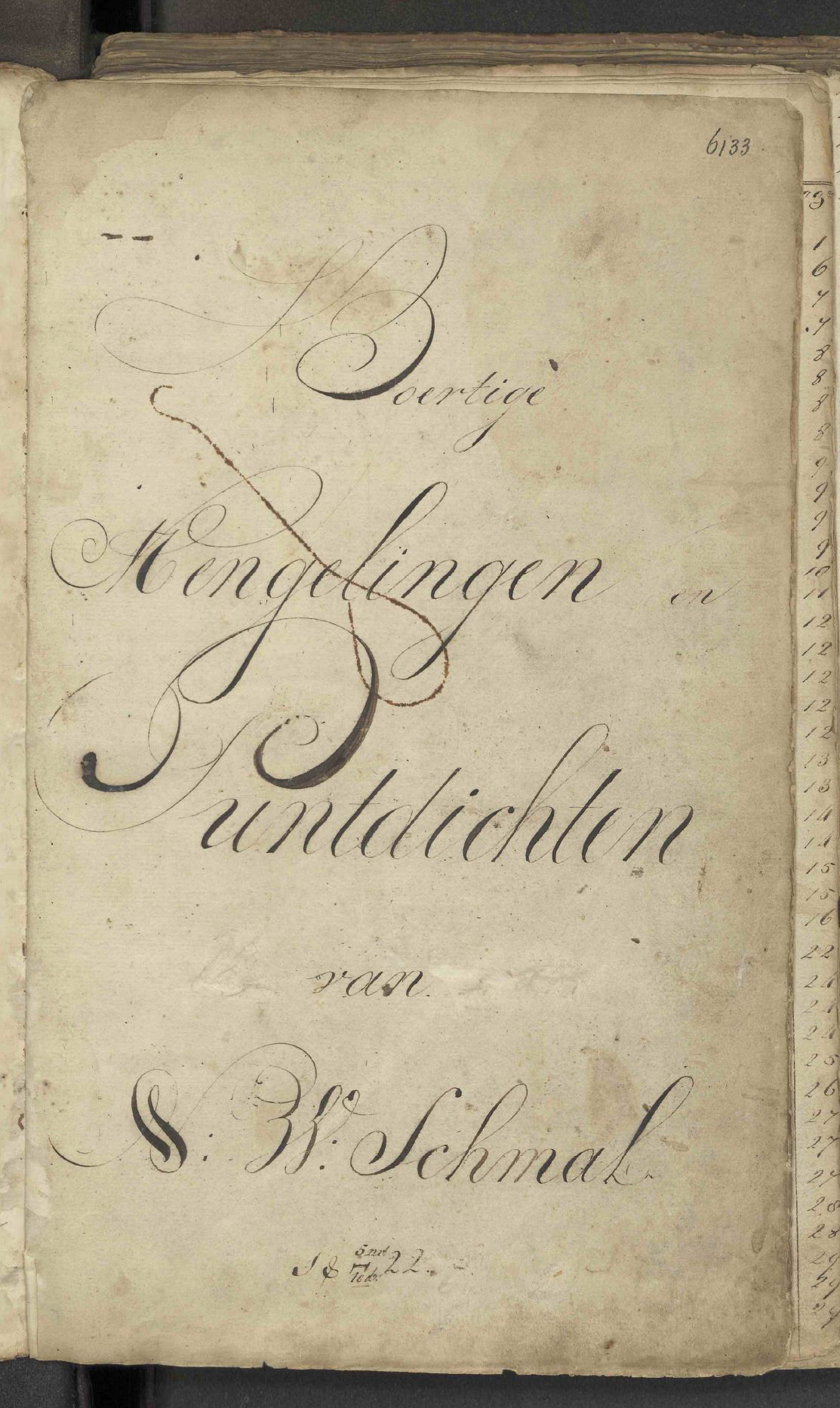

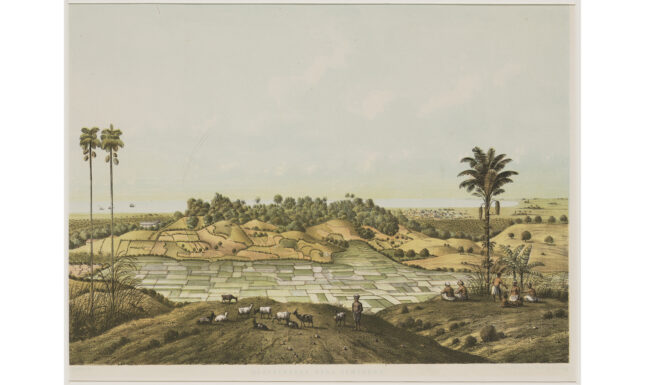

Leiden University Libraries holds an exceptional manuscript by a certain Nicolaas Willem Schmal (1796-1837): 'Boertige Mengelingen en Puntdichten'. It was purchased in 1997 and has not been studied up to now. It mainly contains comic verses but also reveals a terrible tragedy.

Schmal was born in Voorburg in 1796. In 1820, he married Helena Renaud (1794-1831), who was born and raised in the same town. They had three daughters: Wilhelmina Helena (1821-1908), Sanderina Johanna (1822-1903) and Catharina Johanna Carolina (1825-1918). Schmal was a soldier: second lieutenant amongst the ‘cuirassiers’ (cavalry soldiers on horseback), stationed in Haarlem.

Schmal wrote the verses in the preserved manuscript during his time in Haarlem. They are not particularly outstanding when it comes to their literary quality. Schmal may have written them in the context of a ‘humorous’ poetry-loving society such as Democriet, which was active in Haarlem at the time.2 They contained typical male humour: Schmal’s verses were particularly peevish of the always ‘bitching’ women. As we, for example, read in the verse ‘A man’s outburst at his wife's grave’:

My wife lies in the grave, and I stand beside her

In vain it is and impossible, too

That I here ungratefully suppress my feelings

Nay, I will never forget her – the last day of her life

Was the first day of my happiness. (p. 14)

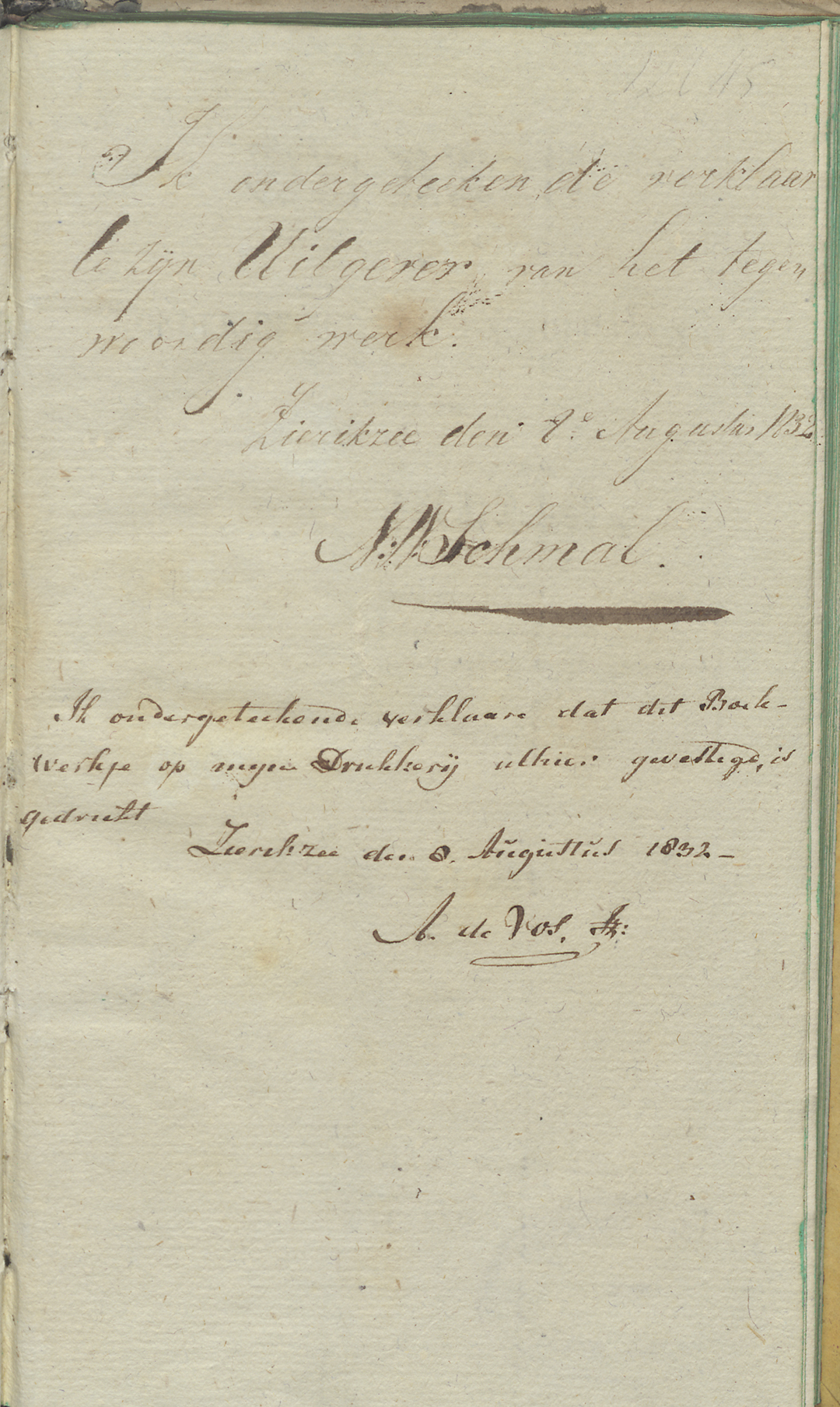

On p. 157 Schmal’s text ends and a friend from Haarlem, a certain Willem Egbert Smit (1800-1835), takes over his pen. Smit writes that he received the manuscript from Schmal as a memento when the latter left for the Dutch East Indies in 1829. He was probably sent there because of the Java War (1825-1830). On 13 November, he travelled on board the frigate Aurora via the Cape of Good Hope to the Indies. There he was appointed second lieutenant in the ‘Vrywillige Jagers‘ on horseback on Java. His promotion to first lieutenant followed in early June 1830.

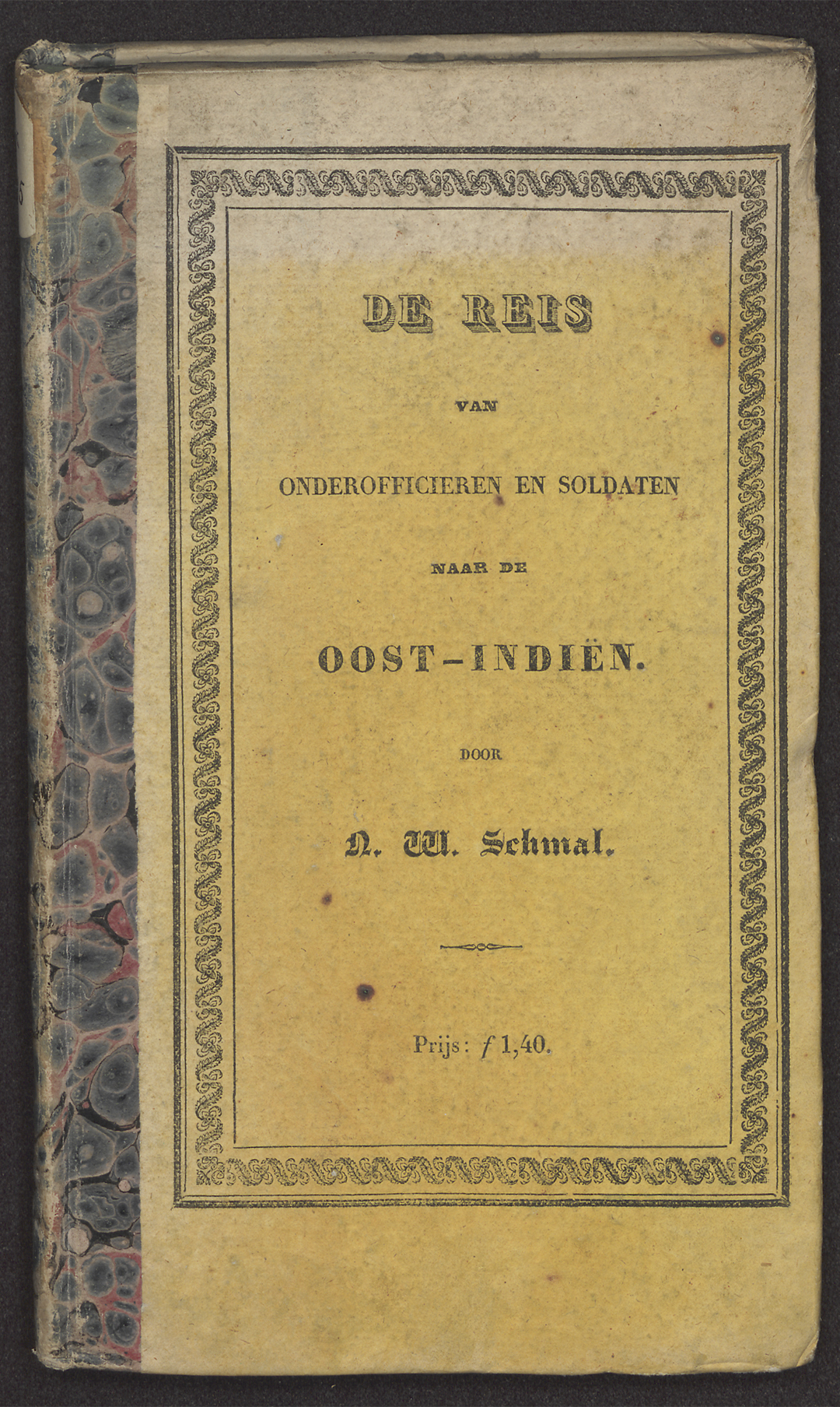

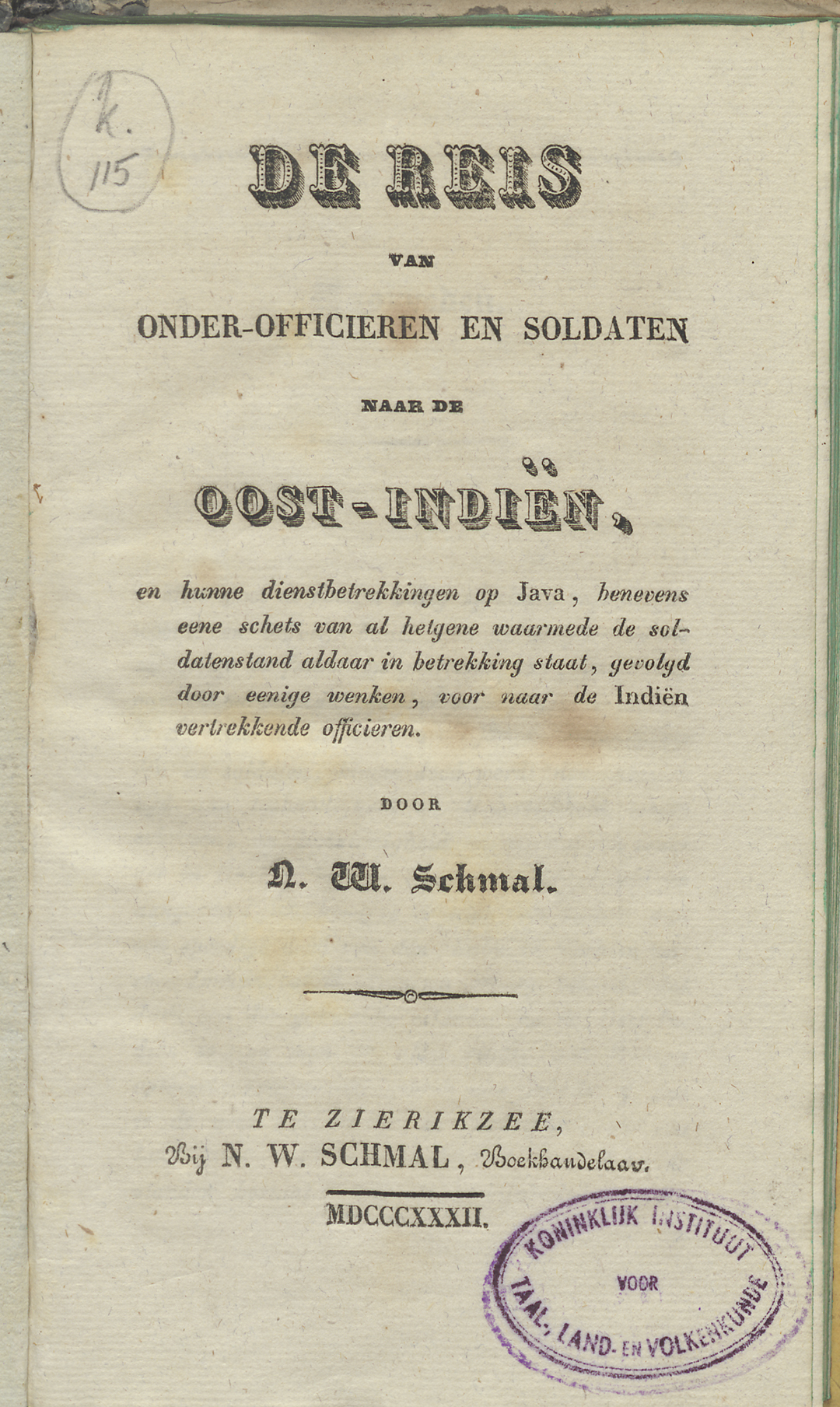

Schmal was to remain in the Indies for only a short time. In 1832, he established himself as a bookseller in Zierikzee. That same year, he published the brochure De reis van onderofficieren en soldaten naar de Oost-Indiën (The journey of non-commissioned officers and soldiers to the East Indies), in which he painted a not very rosy picture of the situation in the colony. ‘One has to have a steel soul in a metal body to withstand all the disasters that befall the soldier in the East Indies’, he remarked. If you were not killed by the natives, you died because of the climate or tropical disease. Those who returned to the Netherlands after their period of service had turned into ‘blind, crippled, deficient necks’, according to Schmal. That is why he wanted to paint young people a realistic picture of the situation in the East Indies. It was not his intention to scare them off, because ‘the Colonies needed troops anyway’, but to tell the pure truth.

The manuscript shows that Schmal also had a personal reason for his negative opinion of the East Indies. His stay there was associated with great sorrow. Schmal did not travel alone to ‘the East’, but with his wife and daughters. Apparently, as an officer, he was allowed to take his family with him. In the remainder of the manuscript, Smit describes how Schmal fared in the colony. Apparently, his wife, Helena Renaud, was pregnant when she left the Netherlands, because she gave birth to a son, Willem, on 30 June 1830 in Semarang (Central Java). Four months later, she and her four children left Semarang and returned to the Netherlands. Was Mrs Schmal perhaps weakened or ill, or was it because of her child?

On their way home, tragedy struck. Six months after his birth, on 14 December 1830, the boy died on board, and exactly three months later, Helena, aged 36, died as well. On 12 April 1831, the ship with the three motherless girls arrived at the roadstead of Texel. When Schmal heard that his wife had died, he asked the governor-general to grant him an honourable discharge. At the end of 1831, Schmal arrived in the Netherlands and embraced his three poor daughters again.

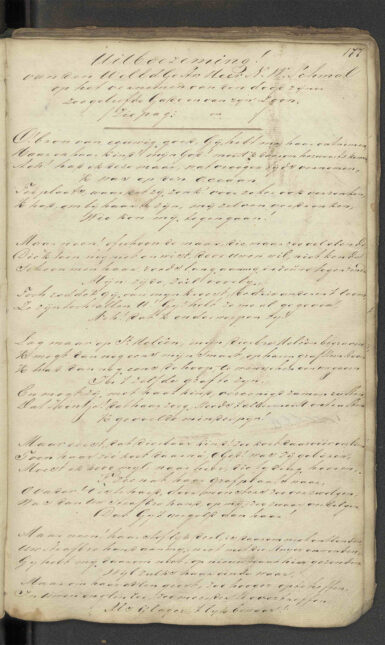

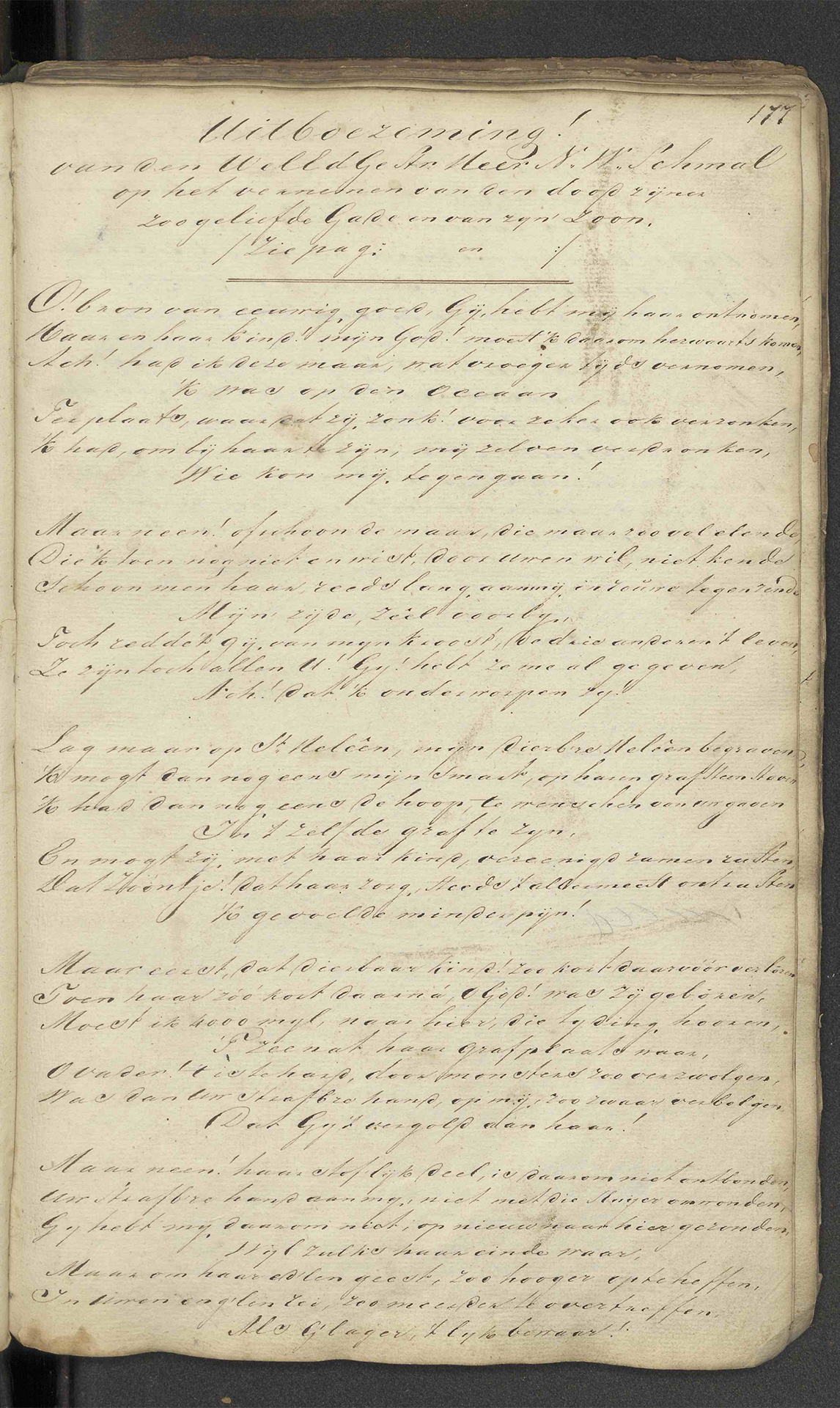

How Schmal felt, can be gathered from the seven-strophe poem ‘Uitboezeming’, which has been preserved in Willem Egbert Smit’s above-mentioned manuscript. Schmal regretted that his wife had been given a seaman’s grave and had not been buried on the island St. Helena. He would have preferred to drown in the ocean so that he could be with her. But he thanked God that He had saved him for his daughters, in whom he recognised his wife.

Because of the care for his children, Schmal married the 35-year-old widow Catharina de Groot (1796-1859) in Zierikzee on 8 August 1832. She gave him two sons. The first child was called Willem – undoubtedly a reference to the son who died at sea. This second Willem also died young, in 1839, at the age of six. But father Schmal did not have to live to see the day, for he himself breathed his last breath on 18 May 1837 at the age of 40.

Next year, it will be 185 years ago that Nicolaas Willem Schmal died. Behind the Leiden manuscript lies a great tragedy, which is closely linked to the Dutch colonial past in the East Indies.

Notes

The manuscript of Boertige Mengelingen en Puntdichten is digitally available in its entirety in the UBL Digital Collections.

1) I wrote more extensively about Schmal in my article: ‘“Eene stalen ziel in een metaal ligchaam”. De reis van N.W. Schmal, vrijwillige jager te paard op Java’, in: Indische Letteren 36 (2021) 4, 253-278.

2) Bert Sliggers, De verborgen wereld van Democriet. Een kolderiek en dichtlievend genootschap te Haarlem, 1789-1869. Haarlem 1995.