Signed 北京: 周培春 畫 Beijing: Zhou Peichun hua – Chinese paintings for foreign visitors

At the beginning of the 20th century, Chinese painter Zhou Peichun started mass-producing beautiful watercolour paintings depicting life in Beijing. Rosalien van der Poel writes about two of his paintings that were recently restored by textile conservator Sjoukje Telleman.

The colourful paintings discussed in this blog once decorated the walls of the Sinological Institute in the Leiden University Arsenaal Building. It is quite possible that they were acquired by J.J.L. Duyvendak (1889-1954), a Dutch Sinologist who worked as an interpreter at the Dutch embassy in Beijing from 1912 to 1918, before accepting a position at Leiden University in 1919. When the collections of the Sinological Institute were moved to the UBL Special Collections in 2016, the two paintings were re-evaluated and valued for their quality and authenticity. In 2021, they were restored and preserved by textile conservator Sjoukje Telleman. In this blog, I will seek to answer three questions: How did Zhou Peichun work? How historically accurate are the depicted scenes? And what is the value of this type of heritage for future generations?

The painter Zhou Peichun and his studio

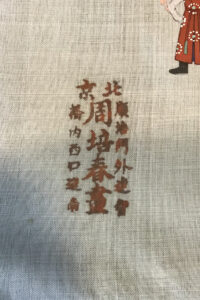

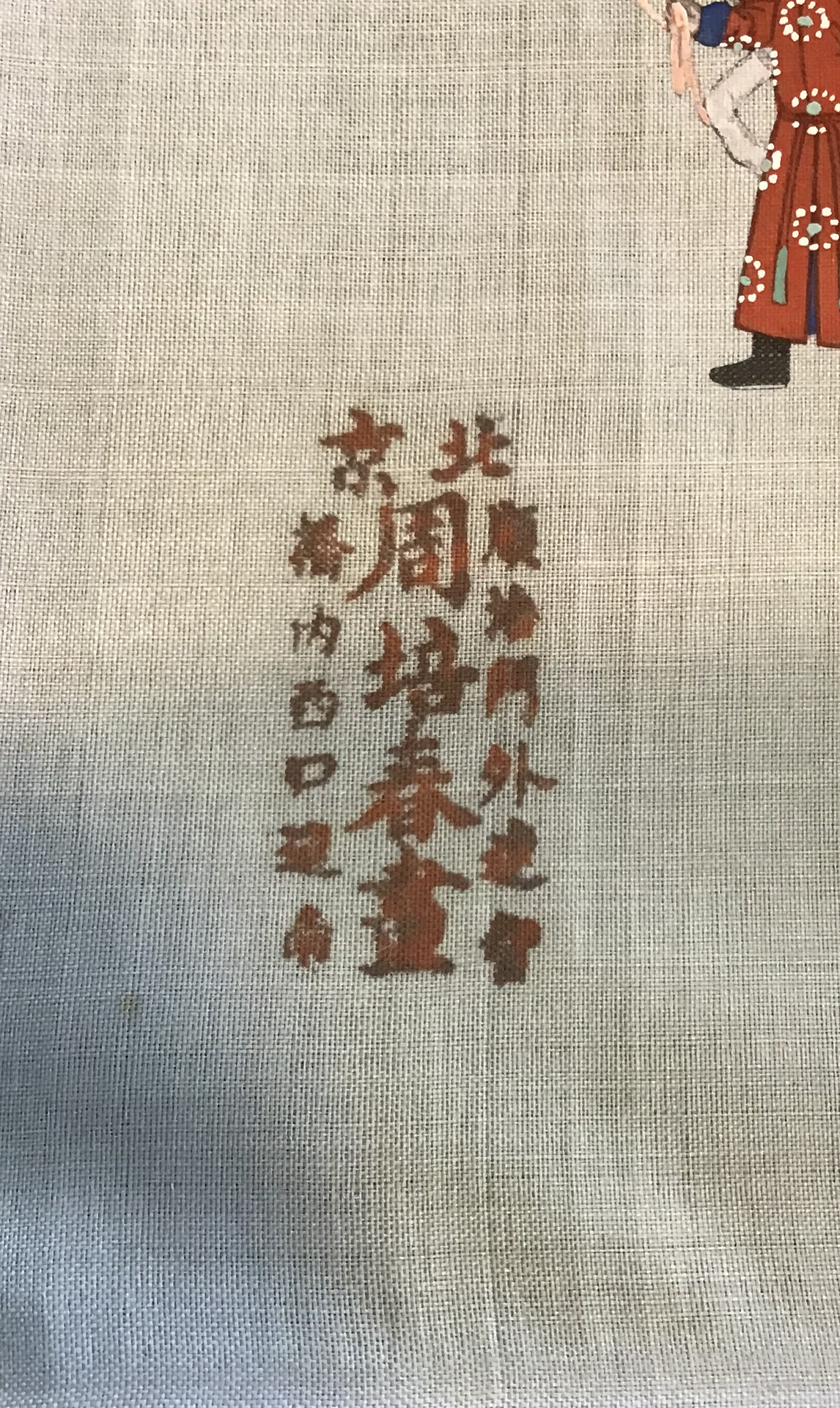

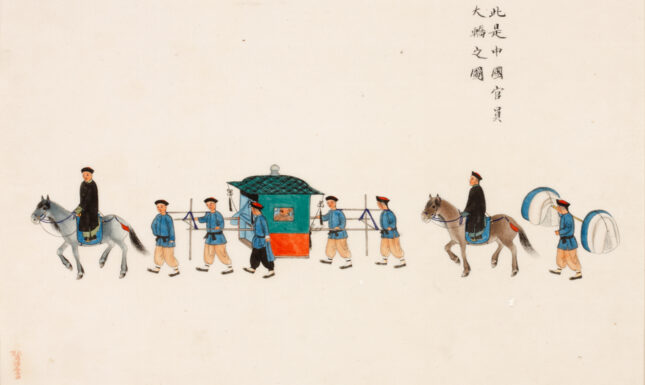

The Chinese (export)painter Zhou Peichun had his studio in Beijing and painted for foreign, mainly Western, customers. He always affixed a small red stamp 北京: 周培春 畫, Beijing: Zhou Peichun hua (Beijing, painting by Zhou Peichun) in the bottom left corner of his paintings, occasionally with an address and directions on how to get to his painting shop. On the two paintings in our Special Collections (Or.28.073 and Or.28.074) the location of his shop can be clearly read: 順治門外達智橋內西口迤南 (South of the west exit of the Dazhi Bridge outside the Shunzhi Gate.)

We know from dated works and visual references in the pictures themselves that Zhou was active as a painter between 1880 and 1910. Judging from the large number of paintings surviving in museum collections worldwide it is likely that Zhou had other artists working for him. The V&A alone has 648 specimens, the Leiden Special Collections is home to 34 images, including the two paintings discussed in this blog. Dozens of watercolours, albums and even similar procession scenes are kept at museums all over the world, from The Hague to Philadelphia. Also, nowadays, private collections of Zhou’s paintings are regularly offered for sale at auction. His works are easily recognizable: Zhou’s pictures are always watercolours and marked with his red stamp. Most images are accompanied by a text explaining what the picture is about.

These explanatory texts are an indication that the anticipated viewer was probably foreign; they were one of his “selling points”, as Ming Wilson, former Deputy Curator of the Far Eastern Department at the V&A calls them. Zhou realized that, to a Western viewer, grasping the meaning of depictions of festivals, weddings, funerals, various means of transport, Chinese customs or scenes from daily life would be quite difficult. So, he added notes beside the painted images. Art historians nowadays also find this information very useful, as the texts provide information on some customs that have mostly been forgotten. Zhou catered to a foreign market with photorealistic paintings of everyday life. It made him and his work stand the test of time.

Procession scenes

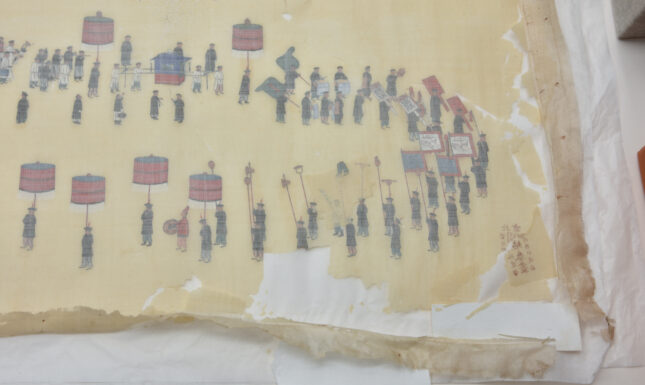

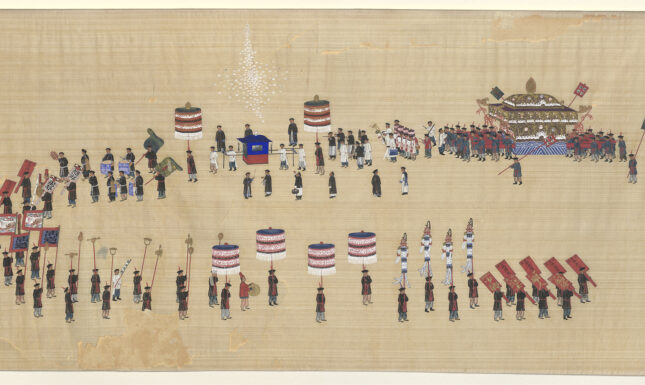

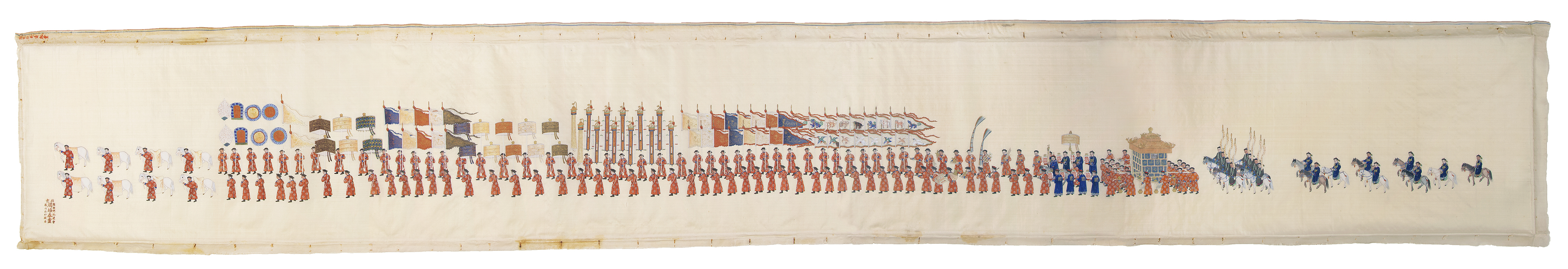

Let us have a closer look at our two paintings. Both depict typical street scenes in the Chinese capital at the beginning of the 20th century: one a funeral procession and one a wedding procession. The painting with a Chinese funeral procession (Or.28.073) is one of the rare works of Zhou Peichun without explanatory text. The watercolour is painted on silk and deviates somewhat from Zhou’s regular size format. Whereas he usually bound thematic albums with twenty to thirty sheets of size 34.5 x 26.5 cm, the funeral procession is 68.4 x 35.5 cm.

From available literary sources like Wilson’s article in Orientations, we know that Zhou faithfully depicted the funerary practice of the time in this painting. What do we see? At the head of the procession, four men carry large red placards citing the titles of the deceased in gold. On the back of the placards is written ‘Deyuan Gangfang’, the gangfang being a specialist shop, which hired out funerary equipment and staff to families of the deceased. The coffin rests on a palanquin borne by two groups of men, sixteen-a-side, which was the correct number of personnel for such a task. The men wear black felt hats, each set with a feather. The four corners of the coffin cover are decorated with a dragon’s head from which tassels are suspended. Colours are also correctly used: the carrying rods are red and the flame-shaped finial (symbol of the rule of the law) on the coffin cover is yellow. In front of the coffin, we can see a man, probably a priest, his two attendants, and behind them four men carrying canopies. They are all dressed in white, the colour of mourning. In front of them walks a group of musicians followed by a smaller, plainer sedan chair, carrying the ‘spirit tablet’ of the deceased. Other details, such as the five pairs of golden objects on long poles, coming after the four canopies, can be identified as melons, axe heads, stirrups, open fists and palms. The use of these objects, as well as the tiger banners, are all corroborated by literary sources. An identical scene is in the collections of the Horniman Museum and Gardens (1996.363) and the V&A (E.2960-1934), both in London.

The second painting shows part of a more festive scene, an imperial wedding procession (Or.28.074). It is quite likely that our painting was once part of a pair. If so, the other part would probably have been a scene like the first painting in a pair of ‘imperial marriage’ handscrolls that was put on auction at Sotheby’s some years ago. In our painting, it looks like we are presented with the second and final part of a large wedding procession, with horsemen walking next to their white horses, men carrying placards with auspicious symbols, lanterns with double xi characters for luck and happiness, and the Eight Banners and their flags painted with animals symbolizing the various official ranks of the bannermen. They are leading a carriage decorated with phoenix finials.

The address stamp on both paintings gives us a clue about the dating of these paintings. This address has existed since at least 1909. The location is visible on one of the maps in the collection of the UBL: (G2309.P4 S1 1985)

Chinese art as cultural heritage for future generations

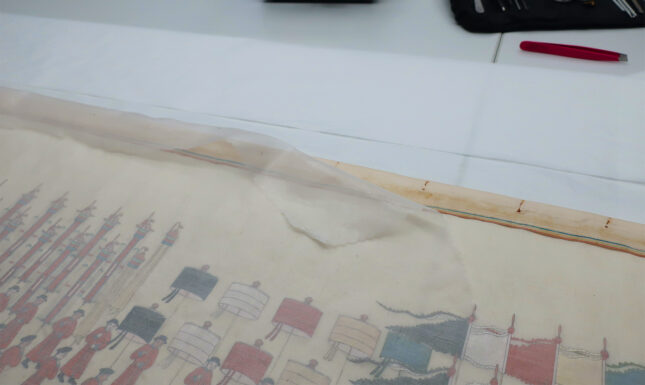

Even though both paintings were recently restored by Sjoukje Telleman they are only accessible online because they are too vulnerable to put on display or to be accessible through the Reading Room Special Collections. Sjoukje gave us some insightful information about the restoration:

“Both paintings arrived framed. The silk fabrics have clearly been in prolonged contact with the now highly acidic strawboard of the frame. This has resulted in considerable damage. The larger work (Or.28.074) looked good, but a few fractures in the surface revealed that the silk had indeed been weakened. The smaller work (Or.28.073), however, was weakened to such an extent that the silk powdered with every touch, causing the object to be slowly lost. To keep the paintings accessible for research, it was decided to conserve them. To delay further weakening and prevent dirt from being fixed during treatment, both objects were first cleaned mechanically. Next, the works were supported from the back with a transparent, silk fabric. A sewing technique for fixing the support proved to be no longer possible, as the needle would cause permanent holes or even powder the silk. Therefore, a glue technique was used to attach the supporting tissue. The smaller painting was so weakened that it was also necessary to support it from the front. For this purpose, an open nylon fabric was placed over the painting. To prevent further movement, the work was mounted on a rigid board. In this way, the work can continue to be displayed.”

Some images of the conservation process.

I would like to emphasize the importance of bringing these paintings back to the stage, even if it is a digital stage. In their newly restored state, they will be accessible for future generations. This revivification says something about the value accrued to them by the curators of the Leiden University Special Collections. I am very grateful to Marc Gilbert, curator for Chinese Special Collections, who asked me to appraise these paintings after their move to the Special Collections. They can truly be counted among its many treasures. As products of a unique era in history, they are informative media conveying historical moments from life in China at the turn of the 20th century.

_____

About the author: Dr Rosalien van der Poel is an art historian and works at Leiden University as Institute Manager of the Academy Creative and Performing Arts. She combines her job with her position as a research associate China at Museum Volkenkunde and board member of the Stichting Vrienden van de UBL and of the Royal Asian Art Society in the Netherlands. In 2016 she received her PhD with the dissertation Made for Trade - Made in China. Chinese export painting in Dutch collections: art and commodity. With her expertise on Chinese export paintings in Dutch collections, she emphatically advocates the significant value of these collections.

Further Reading:

Ming Wilson, 'As True as Photographs: Chinese Paintings for the Western Market', Orientations, V.31, no.9, November 2000.