Petrus Camper’s facial angle theory - and the missing monkey

Illustrations in the Leiden Special Collections throw new light on the making of Petrus Camper’s ‘facial angle theory,’ which proved influential in the development of scientific racism.

This illustration is from the Verhandeling van Petrus Camper, over het natuurlijk verschil der wezenstrekken in menschen van onderscheiden landaart en ouderdom (1791, Utrecht) and shows the “facial angle” theory of Dutch naturalist and anatomist Petrus Camper (1722-1789). Camper was born in Leiden, studied at Leiden University, and held professorships in Franeker, Amsterdam, and Groningen. Among Camper’s many papers in the Special Collections of Leiden University and the University of Amsterdam, this illustration is the most infamous.

Camper’s facial angle theory stated that the jaw’s projection relative to the forehead metrically differentiated species, individuals of different ages, and among what Camper called human “landaarden” (regional varieties). In the Verhandeling, Camper wrote that all animals had smaller facial angles than humans, that Europeans had the largest facial angles among humans, and that larger facial angles were the most beautiful. The book was foundational to the development of scientific racism in the decades after Camper’s death.

The facial angle has received significant scholarly commentary, almost all focused on Camper’s publications. Camper’s archive in the Leiden University Special Collections sheds new light on the development of Camper’s theory.

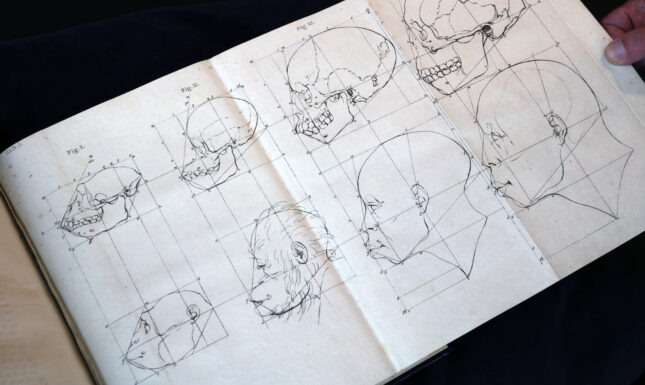

The drawing above is the first illustrated plate in the Verhandeling. The skulls in the illustration are, from left to right, those of a monkey (which Camper describes only as a tailed African monkey), an orangutan, a young boy from Angola, and a Kalmyk man from Central Asia. Camper reports that he drew the skulls from direct observation.

The second plate of the treatise, shown above, shows skulls which Camper described as “European.” This plate is a continuation of the first, showing an increase of the facial angle from monkey, to ape, to African and Asian, and, finally, to European (with the furthest to the right representing an imagined aesthetic ideal).

Camper wrote that the orangutan depicted in the first plate, dated in Camper’s hand to 1768, was from the first orangutan head that he had dissected. But from Natuurkundige verhandelingen van Petrus Camper over den orang outang (1782), we know that Camper first dissected an orangutan only in 1770. That report included the following illustration, which exactly matches the first plate of the facial angle text, dated to 1768.

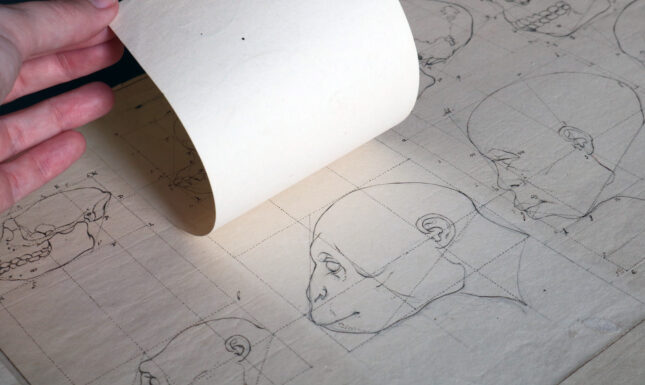

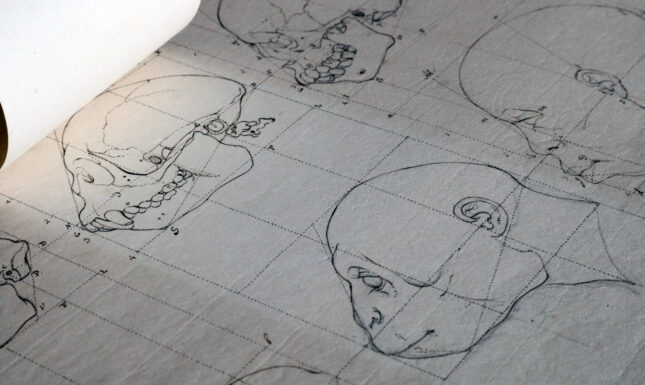

A folder of drawings in the Leiden University Special Collections provides the answer to the discrepancy. It contains a drawing, dated on the bottom right by Camper’s hand from 1768, which is Camper’s oldest known sketch of the facial angle (images 4-7). The illustration is the first in a packet of drawings corresponding to the plates in the final text. A piece of paper depicting the orangutan dissected in 1770 is pinned onto the larger sheet of paper.

Underneath the pinned orangutan drawing is an illustration of a different primate, one that did not appear in the published version of the facial angle. The skull appears monkey-like, but is drawn disproportionately large next to the human skulls. Camper noted that this skull’s facial angle was 50 degrees, intermediate between the smaller monkey on the left (42 degrees) and the humans on the right (70 – 80 degrees).

Images 4-7: Petrus Camper archive and collection (ubl184), BPL 247 IThere is no drawing or mention of this monkey in the published Verhandeling. What was this missing monkey? Published notes of Camper’s lecture in Amsterdam’s drawing academy, where he first lectured on the facial angle in 1770, provide an explanation:

“Thus, birds have the smallest facial angles, and facial angles increase as the animal’s form approaches the human face. Such is clear with the monkey heads, of which the first has a facial angle of 42 degrees, and the following a facial angle of 50 degrees. This last one is the head of a monkey, commonly named the ‘death’s head monkey’ (Doodshoofden), which is most similar to humans.”

The “death’s head monkey” (named for their facial fur’s skull-like pattern) is known in English as the squirrel monkey (genus Saimiri). This small monkey, usually under one kilogram, is native to Central and South America.

Why did Camper switch his squirrel monkey illustration for an orangutan, which he dissected only after his first sketch of the facial angle? Camper believed that the orangutan was a closer approximation of human form: he reports that the orangutan’s facial angle was 58 degrees. Moreover, the placement of the orangutan in Camper’s facial angle treatise may have underscored Camper’s scientific authority: Camper’s 1770 orangutan dissection was allegedly the first in Europe. (Squirrel monkeys had been described by naturalists much earlier.)

Over two hundred and thirty years after Camper’s publication of the facial angle, despite intensive attention, its archive reveals new insights. Further exploration of the switch from squirrel monkey to orangutan would require a much longer consideration of the role of apes in defining the boundaries of the human and the animal in European Enlightenment thought, and the colonial networks supplying Camper and other European naturalists with objects and remains from across the world in the eighteenth century. It would also invite further investigation of how, why, and when Camper acquired human and animal bodies for his anatomical and natural historical collection. Some of these themes are taken up in a recent issue of De Boekenwereld focusing on Camper. They are also on display in a current exhibition (opening March 2025) at the University Museum of Groningen: “Entangled Histories: Science and Colonialism in the Collection of Petrus Camper.”

Acknowledgement:

With thanks to Lisette Jong (University of Amsterdam) and Alissa van der Scheer (University Museum Groningen) for their contributions to this research.

Further reading:

Lisette Jong. 2024. “Orang-oetans op de snijtafel.” De Boekenwereld 40(3), 34-39.

About the author:

Dr. Paul Wolff Mitchell is a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam and a member of the project “Pressing Matter: Ownership, Value and the Question of Colonial Heritage in Museums.” His research concerns the collection of human remains and the history of medicine, anthropology, natural history, and scientific racism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and their enduring legacies. He has published on these themes for both scholarly and popular audiences, and curated exhibitions in both the United States and the Netherlands.