Depicting the Qing Empire's Periphery: A Miao Album with Painted Maps

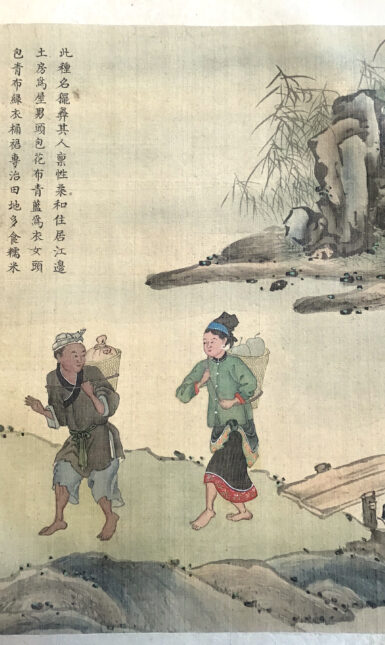

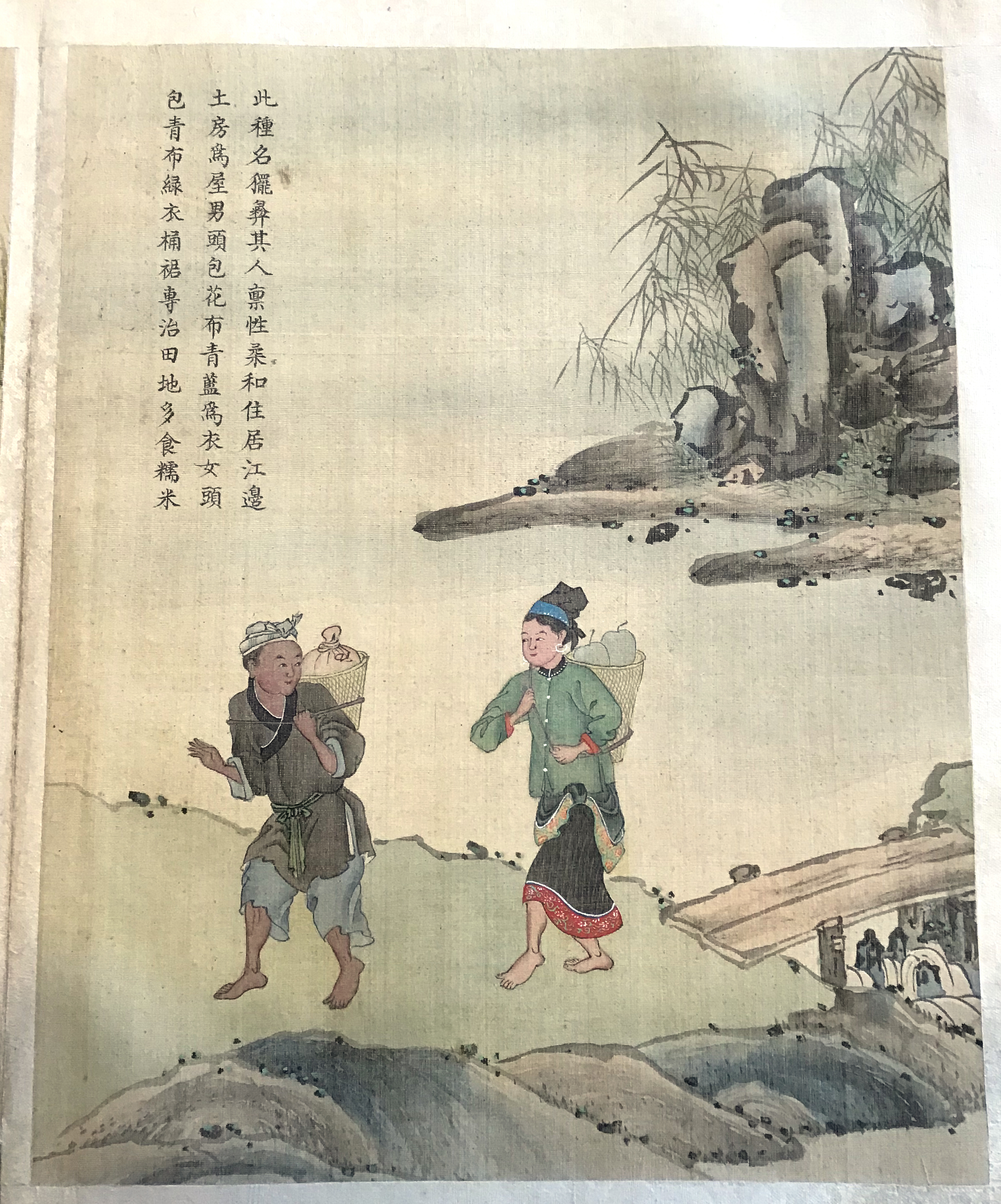

Miao albums depict people and places in the Chinese southwestern borderland, but very few of them contain maps of the region. The painted maps in the Leiden University Libraries Miao albums may offer insight into the history of the region and its administration.

With the state expansion in its southwest frontier during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, the central imperial government gradually replaced hereditary native officials (tusi 土司) in the region with direct state administration. In this context, China’s southwestern borderland, especially Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces, assumed an increasingly important role in the empire. In the meantime, literati became more enthusiastic about exploring this region, leading to the production of travelogues, such as one by Xu Xiake 徐霞客 (1587-1641), and paintings, such as one by Qiu Ying 仇英 (1494? -1552), documenting its geography and people, who were often referred to as Miao 苗 or Yi 夷. Notably, the Qing court officially sponsored the compilation of Miao albums no later than the Yongzheng period (1723-1735). This further stimulated the boom of such albums, of which the two-volume Miao album, acquired by Leiden University Libraries (UBL) in 2022, stands as an example. Miao albums have drawn international interest, as a larger number of them are housed in European and American museums and libraries than in China.

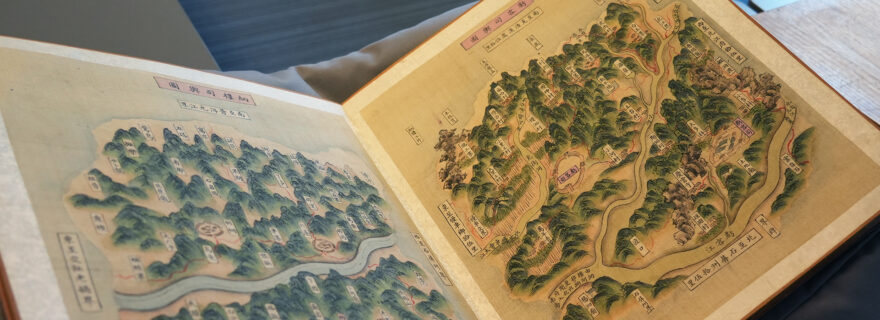

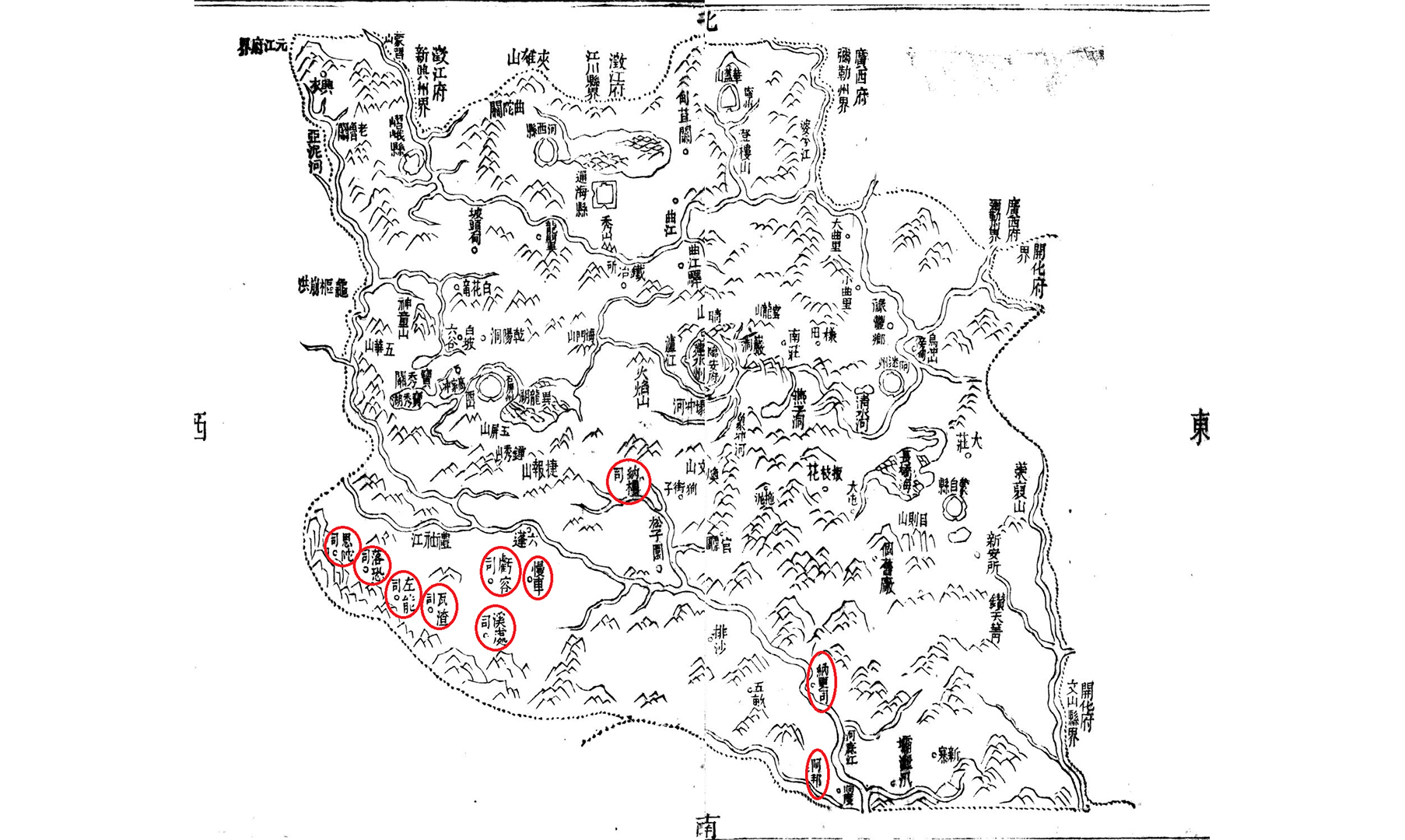

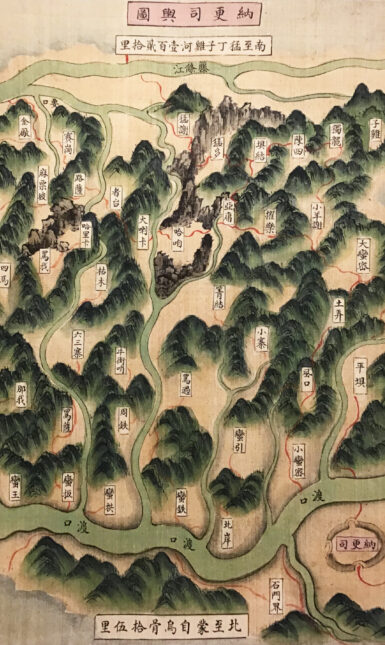

This Miao album in the collections of the UBL is distinctive from others in that its second volume contains ten maps — very few Miao albums contain maps. The maps suggest that the ethnic groups depicted in both volumes were from Lin’an Prefecture 臨安府, Yunnan Province. According to the local gazetteers of Lin’an, during the Qing dynasty, Lin’an consisted of four subprefectures, four counties, and several tusi-controlled districts. However, the ten maps only concern the tusi districts. The number of the tusi districts in Lin’an was most likely finalized at ten in the first half of the Kangxi period (1662-1723), so this album must have been created later than that. According to the local gazetteers, the ten tusi offices (which are marked with red circles in Map 1) were all in charge of civilian affairs, while a tusi assuming military functions was only established several decades later in the Yongzheng period, which was not included in the maps. It is highly questionable whether this military tusi was a normal tusi office because the Lin’an prefectural gazetteer compiled in the Jiaqing period (1796-1821) still recorded ten tusi offices in Lin’an.

This album is untitled. Though this genre is generally called Miao albums, this album may have contained Yi, instead of Miao, in its original title for the following reasons: first, most extant albums about Yunnan have Yi in their titles, and second, the character, Miao, never appears in the names of the ethnic groups in this album.

The precise connection between the figure paintings and the maps in the album remains unclear. The inscriptions accompanying each ethnic group in the figure paintings, for example, do not specify the corresponding tusi district it belonged to. Similarly, the maps do not provide any information about this either. There are four possible explanations for this gap of knowledge: 1. This album may have been intended to be used together with other sources that would have provided more information. 2. The compilers of the album may have assumed that the readers would have had sufficient knowledge to discern the connection on their own. In this case, the album may have been made for local officials in Lin’an or Yunnan in particular. 3. The connection may not have been considered important. In this case, the album was possibly made for the export market or the result of an order from superior officers. 4. The two parts were initially made separately but later merged into one set.

The maps feature land routes connecting various villages despite rivers playing significant roles in this area. The land routes are marked with red lines, occasionally interrupted by rivers. Whether the roads were connected by ferries or bridges at the river crossings is not always clear. The maps also prominently feature city walls and farmlands, suggesting a potential process of Sinicization and the prioritization of agriculture. In addition to the names of villages, the maps highlight the presence of temples, notably Earth God temples, and Daoist and Buddhist temples. Furthermore, the maps provide information about some local products of the region, such as areca palm and gold mines. All these elements serve to incorporate the local resources into the overarching imperial vision of the Qing court.

________

Further Readings:

- Deal, David M., and Laura Hostetler. The Art of Ethnography: A Chinese "Miao Album." Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

- Ge, Zhaoguang 葛兆光. “Hua 'sheng’ cheng ‘shu’?: Cong Qingdai ‘Miaoman tuxiang’ sikao minzu shi yanjiu zhong de wenti” 化“生”成“熟”?——從清代“苗蠻圖像”思考民族史研究中的問題. Gujin lunheng 古今論衡, 2019 (33): 4-33.

- Herman, John. “Collaboration and Resistance on the Southwest Frontier: Early Eighteenth-Century Qing Expansion on Two Fronts.” Late Imperial China, 2014, Vol.35 (1): 77-112.

- Hostetler, Laura. Qing Colonial Enterprise: Ethnography and Cartography in Early Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Zhu, Jing. Visualising Ethnicity in the Southwest Borderlands: Gender and Representation in Late Imperial and Republican China. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt of gratitude to Professor Lin Fan for her inspiring comments and editing. I also want to thank Marc Gilbert for his kind help.

About the author

Jialong Liu is a PhD candidate at KU Leuven studying Chinese history.