Old Manuscript Dictionaries of Chinese: New Connections through the work of Francisco Diaz and Appiani's Copy

The Leiden Special Collections surprised us with another version of the so-called Vocabulario de letra China written by Francisco Diaz.

Western interest in the Chinese language arose at the end of the 16th century, when the first European missionaries arrived in China and its surroundings, mainly from the expanding empires of Portugal and Spain. As a result the Spaniards produced several vocabularies or Artes of the Chinese language (especially Chinchea: Hokkien 福建話 or Southern Min 閩南語), as it did Dominican Friar Juan Cobo (1547-1493); but no Chinese-Spanish vocabulary from this period has been passed down to us.

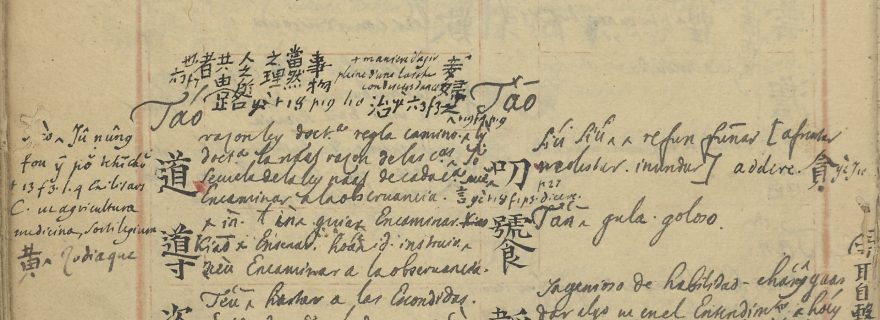

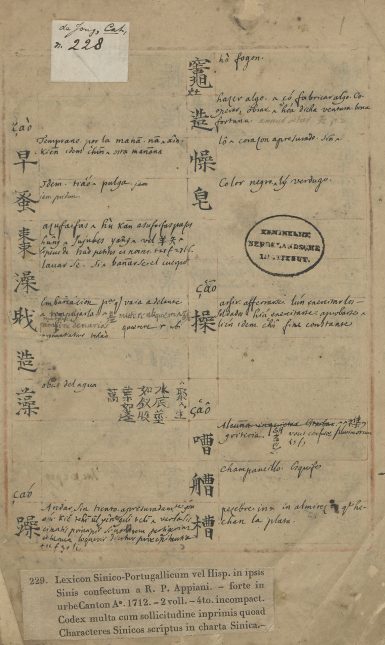

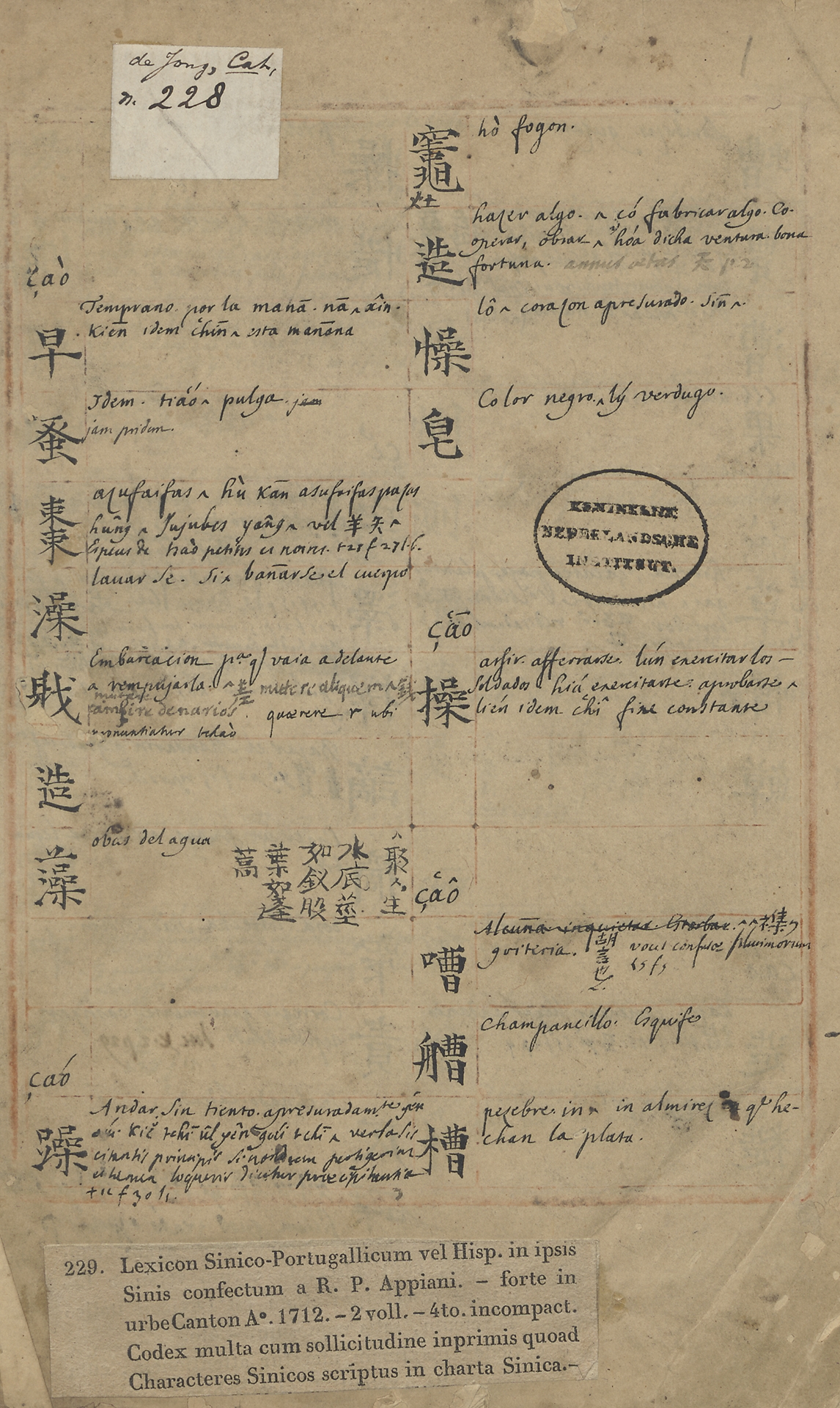

Later, efforts by Western missionaries were focused on the language spoken by the mandarins and the court elite, the Guanhua 官話. Missionary linguistics has provided us with a few manuscripts from the 17th and 18th centuries: small encyclopedias of inestimable historical, cultural, and linguistic richness, among which especially the *Vocabulario de letra China (1640-1643) by Dominican Francisco Diaz (Su Fangji 蘇芳積 1606-1646) stands out. His work was profusely copied, resulting in no less than ten known surviving volumes today, previously studied by Otto Zwartjes, Henning Klöter, and Emanuele Raini. The Leiden’s copy at issue in this blog is of great historiographical value. It was mentioned by Pieter de Jong in 1862 and described by Jan Just Witkam and Koos Kuiper in 2005. Donated by King William I to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, it is held at the Leiden Special Collections since 1856.

This volume, copied from the one held in the Staatsbibliotek in Berlin (now in the Jagiellońska Library in Krakow), is particularly valuable since it was made by, or belonged to Italian Lazarist Luigi Antonio Appiani (Bi Tianxiang 畢天祥 1663-1732) around 1712, although the volume is not dated. Appiani was a key figure in the history of cultural exchanges between the Catholic religious orders and the Chinese court, as he served as interpreter for Papal legate Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon (Duoluo 多羅 1668-1710) in 1705. He served in this position throughout a famous and complex debate called “The Chinese Rites Controversy”, which focused on the impossibility of reconciling certain traditional practices of Chinese converts with the Catholic faith, particularly those that were related to ancestor worship, and the cult of Confucius.

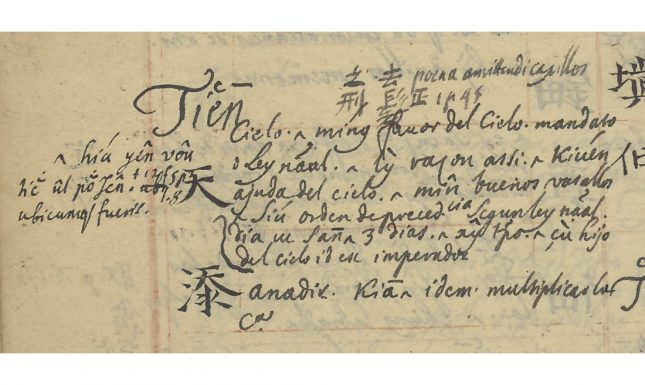

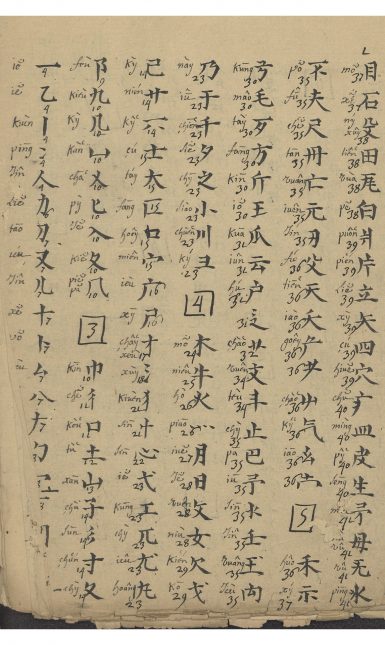

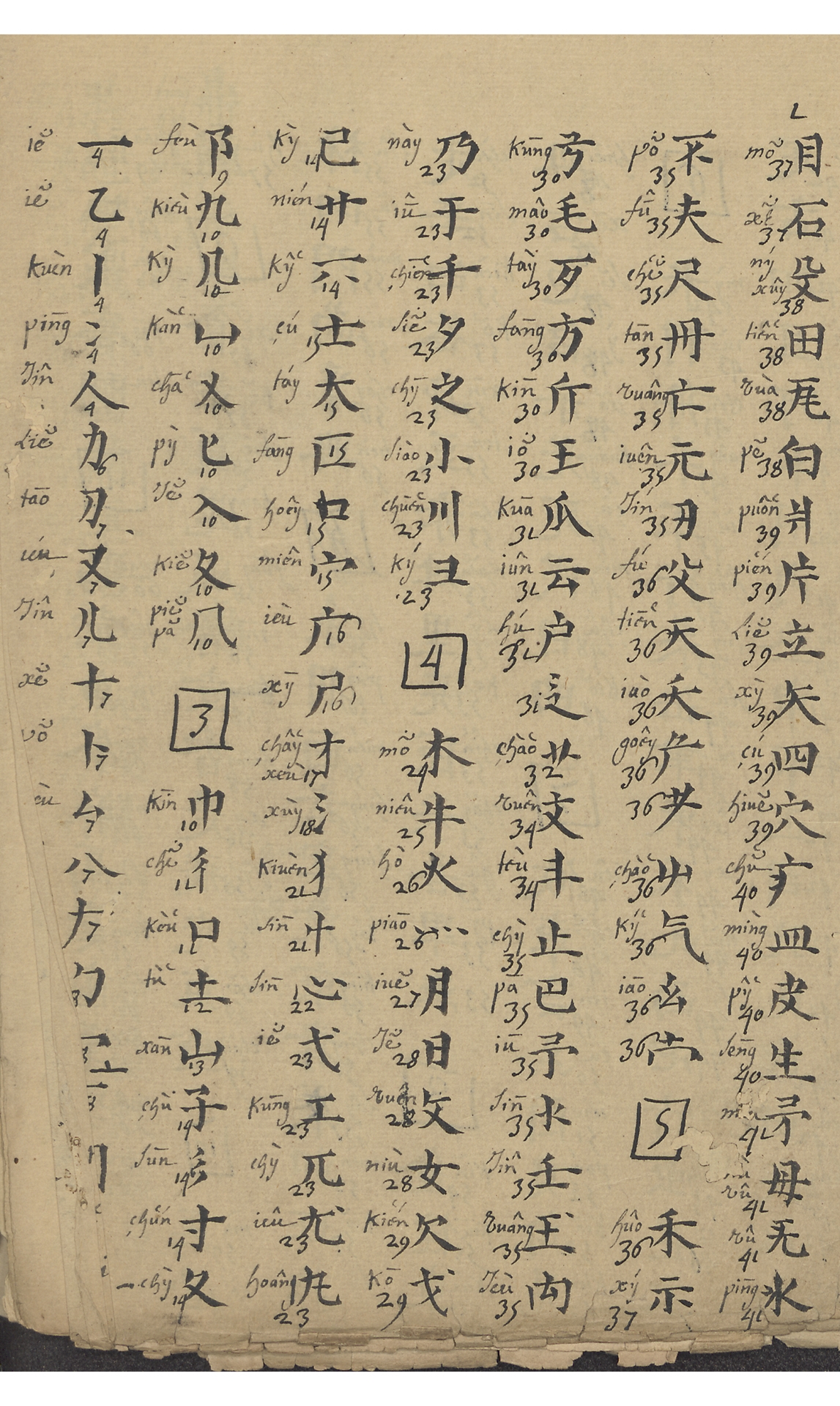

The vocabulary of Diaz copied by or for Appiani not only demonstrates the value of the survival of these first dictionaries, which were consulted for many decades in a fluid exchange of knowledge between religious orders, but also the importance of correcting and updating their contents, along with grammatical and phonetic adjustments in accordance with the evolution of a living language. In this regard, its index of 284 Chinese radicals seems to have been added later.

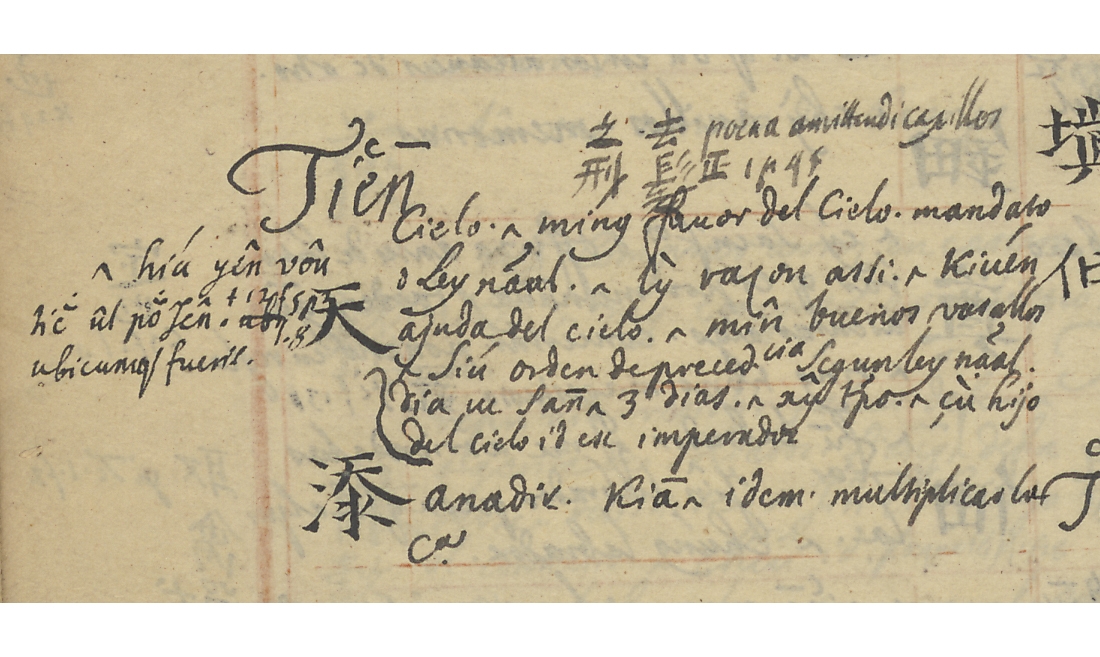

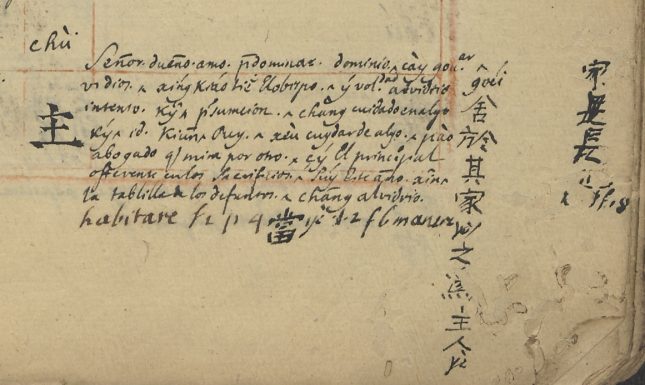

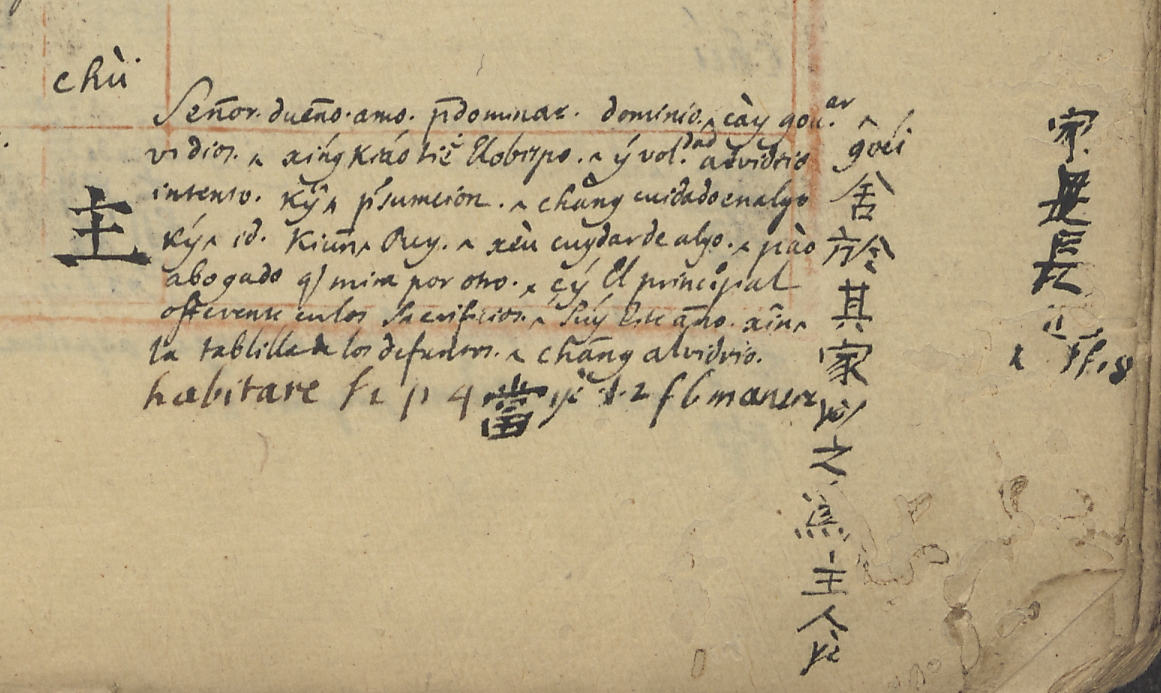

This kind of index became popular through Franciscan Basilio Brollo (Ye Zunxiao 葉尊孝 1648-1704) and his manuscript dictionary of Chinese-Latin (circa 1694), containing an index most likely based on those in Chinese dictionaries such as the Character Collection (Zihui 字彙 1615) by Mei Yingzuo 梅膺柞 and its expanded appendix by Zhang Zilie 張自烈: Correct Character Mastery (Zhengzi tong 正字通). Furthermore, Appiani's volume is full of amendments and additions, written in Spanish, Latin, and French. Some sentences calligraphed in the margins are verbatim quotations from important works of Chinese culture and thought, often Confucian and Neo-Confucian texts, because of the interest shown by missionaries, especially Jesuits, in these schools of thought.

Compared to the volume in Krakow, Appiani's copy provides many more elements of analysis regarding Chinese language and culture, as it contains many more entries, explanations and additions, although it too possibly relied on earlier dictionaries written by other Western missionaries. Apart from Appiani’s copy of Vocabulario de letra China, the Leiden Special Collections holds two handwritten dictionaries of Chinese-Portuguese (Or. 1929), similar to a volume in the Jesuit Archive ARSI. They were apparently brought to the Netherlands by Jesuit Carlo Turcotti (1643-1706) – who was in contact with Appiani – when cultural exchanges between China and Europe were at their peak and these precious volumes were as rare as they are now.

Author: Dr. Maria Teresa (Maite) Gonzalez Linaje is an independent scholar with the TRAMA Research Team at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Further reading:

Zwartjes, Otto. “El Vocabulario de letra china de Francisco Díaz (ca. 1643) y la lexicografía hispano-asiática”, Boletín Hispánico Helvético: Historia, teoría(s), prácticas culturales 23 (primavera 2014): 75-76.

Kuiper, Koos. Catalogue of Chinese and Sino-Western manuscripts in the central library of Leiden University. With contributions from Jan Just Witkam and Yuan Bingling. Leiden: Legatum Warnerianum at Leiden University Libraries, 2005.