More than a costume party. Costumes for the Leiden Student Pageant of 1910

Within the field of costume history, fancy dress can be a rather complicated and neglected category. Are we looking at ‘fake’ clothes or well-made imitations? Research can reveal some interesting facts about its production, its previous owners, and their motives for ordering these clothes.

The Leiden Academic Historical Museum at the Rapenburg houses an intriguing collection of fancy dress costumes and accessories, covering a period from the second half of the 19th century to 1910. The costumes were worn during the lustrum festivities of Leiden University, which traditionally culminated in students’ pageants. Students that could afford such a festive but rather costly attire paraded through the city, thereby confirming their social status while re-enacting an actual historical parade. Most of these garments were made by expert hands, offering skilled but expensive luxury to the students who strived for historical accuracy. I looked more closely at several costumes of the pageant of 1910, a spectacular event with a great deal of splendour, but also excessive cost overruns.

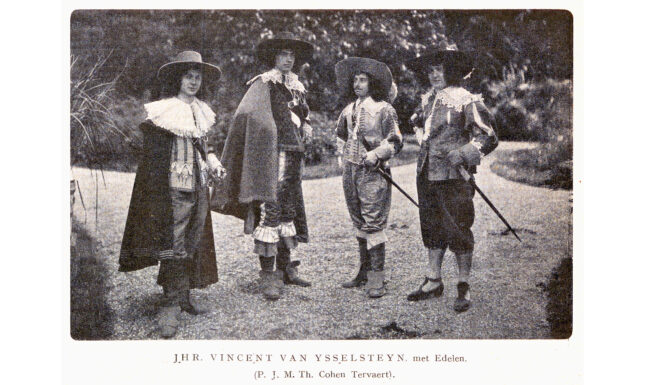

‘Jonkheer Van Ysselsteyn’

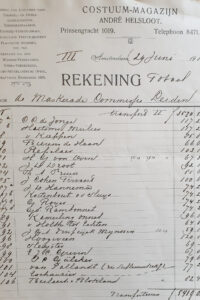

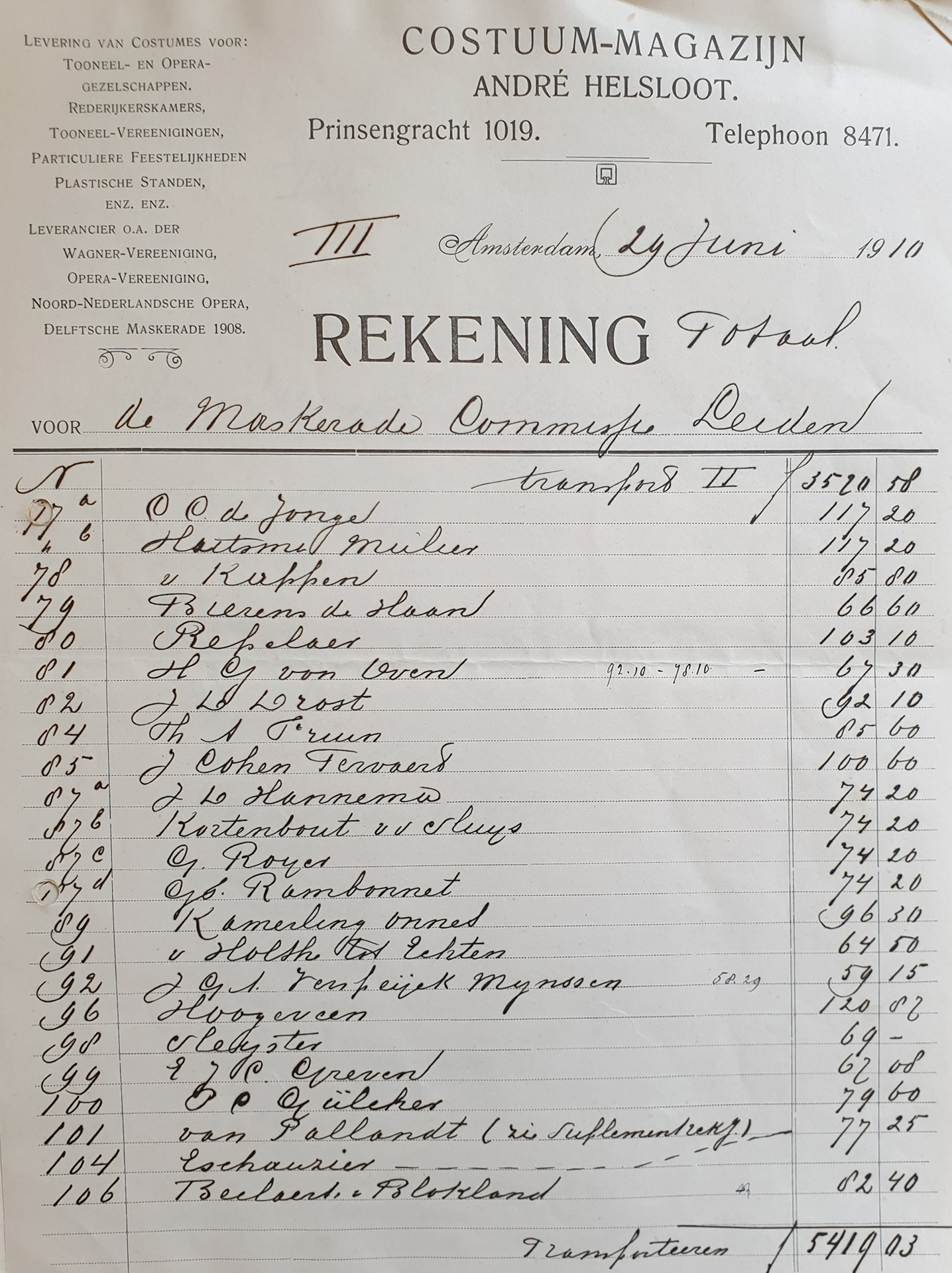

One costume of light blue satin silk was worn by Jozef Marie Theodoor Cohen Tervaert (1890-1960). It was donated to the museum along with all its corresponding accessories: hat, boots, gloves, spurs, collar, wig and dancing shoes. The twenty-year-old doctor’s son took on the role of ‘Jonkheer Vincent van Ysselsteyn’, a high-ranking officer in the retinue of ‘Prince William II of Orange’. The yellow silk lining contains the label of the then well-known Amsterdam costumier André Helsloot, who had previously worked together with artistic director Henricus Jansen for the pageant of 1908, in Delft.

Fortunately, we also know what the costume looked like at the time Cohen Tervaert was wearing it. His photograph was taken at the festival grounds near the Zoeterwoudse Singel, during the so-called ‘monstering’. It was here that the final fitting of all costumes took place ‘in public’, several days before the start of the festivities. Photographs of named participants who played the main roles were published in the illustrious magazine Pak-me-mee. In this special ‘masquerade edition’ readers could find a great deal of historical detail about the chosen theme: the Joyous Entry (‘Blijde Incomste’) of stadtholder Frederick Henry and Queen Henrietta Maria of England, which took place in Amsterdam in 1642.

Today, the costume is in relatively good condition. As Cohen Tervaert was rather small in stature, finding a suitable mannequin to mount his costume for the recent photography was quite a challenge. Only a mannequin of size 176 was suitable, but even then, its feet had to be removed to get its legs into the rather narrow boots. In 1910, Elias, the bootmaker from Haarlem, also complained about the desired cut of the boots, as we can read in his letter to the organizing pageant committee. This letter has survived in the Minerva Archives at Heritage Leiden. Cohen Tervaert’s name is found on several invoices as most of his fancy dress wardrobe was made-to-measure.

The whole dress-up of 1910 is quite well-documented. Several original costume drawings have been preserved. Invoices indicate suppliers of luxury from not only Dutch places such as The Hague and Amsterdam but also from Brussels and even Paris, proving that Henricus Jansen and the pageant committee went for the best quality of materials only, in their communal desire to look splendid. Many yards of rustling silk and heavy velvet fabrics were ordered from renowned Dutch manufacturers like Pander & Zonen and Maison Hirsch, but also from exclusive French wholesale firms like Tassinari and Cornille. Wigs and gloves clearly were of lesser importance: every single one of those was delivered by Leiden-based suppliers Hoppezak and Van Hooff.

‘Women of Liberty’

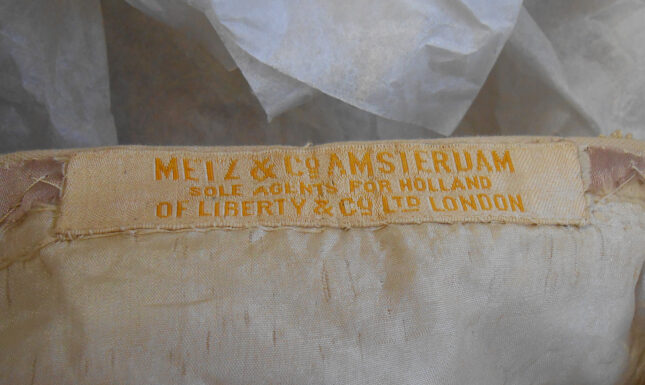

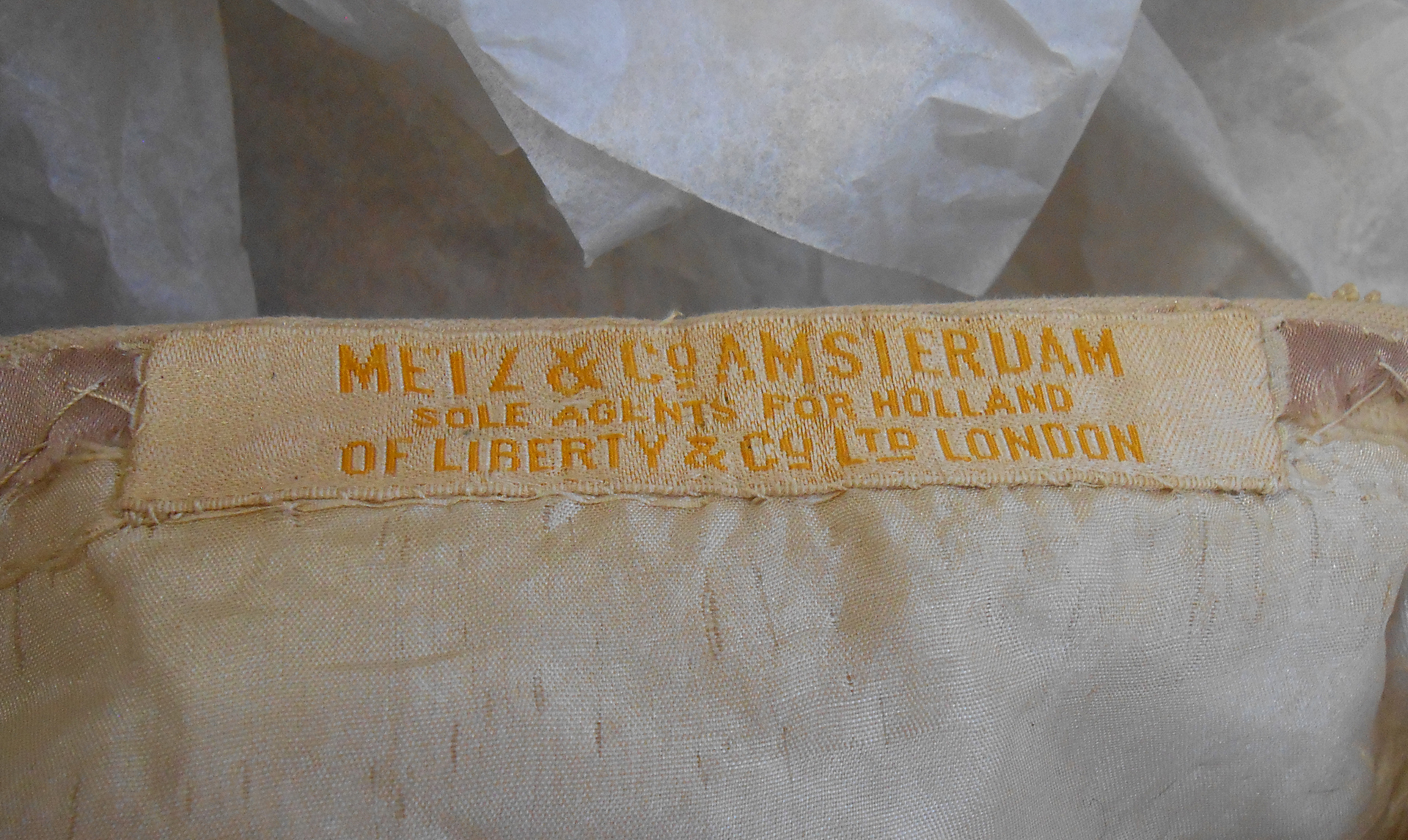

At Heritage Leiden, I also came across several bills of Metz & Co, Amsterdam: the exclusive Dutch agent for Liberty silks imported from London. At that moment, Metz was ‘the place to be’ for the more avant-garde Aesthetic Dress designs and high-quality silk fabrics in soft colours. In 1910, it was for the very first time that women were asked to take part in the Leiden pageant. Henricus and the committee ’went for gold’ and ordered fifteen costumes from the highly esteemed Metz atelier. These gowns were even discussed in several Dutch newspapers that followed every part of the preparations.

One 1910 dress, catalogued as ‘from an unknown female student’ in a refined mauve and brownish-purple, seemed very ‘Liberty’ to me. Despite its very fragile condition, it was such a thrill finding the Liberty label while inspecting the inside. In the Gedenkboek, the lustrum album, I found a photograph of a lady wearing the dress, unfortunately without her name accompanying the picture. The Gedenkboek was helpful in that it mentioned only one mauve and purple dress. With the help of a newspaper report, I found out that this dress was worn by Wilhelmina van Oordt (1890-1971), in her role as ‘Mauritia Eleanor, princess of Portugal’. Wilhelmina was the daughter of a wealthy manufacturer of roof tiles from Alphen aan den Rijn. The history of the ‘nameless’ dress could finally be restored. More costume history and interesting stories from this ‘special collection’ are waiting to be told.

About the author: Rosalie Sloof works as a freelance costume historian for Dutch museums with different costume collections. She published articles about the wardrobe of the family Van Loon in Amsterdam, fashion at Scheveningen during the belle epoque and fancy dress costumes at the Modemuseum in Antwerp.

She will publish a more in-depth article on this topic in Kostuum, the yearbook of the Nederlandse Kostuumvereniging in December 2021.

Further Reading

Photo's by Ben Grishaaver.