Medieval manuscripts in the classroom: on site or online?

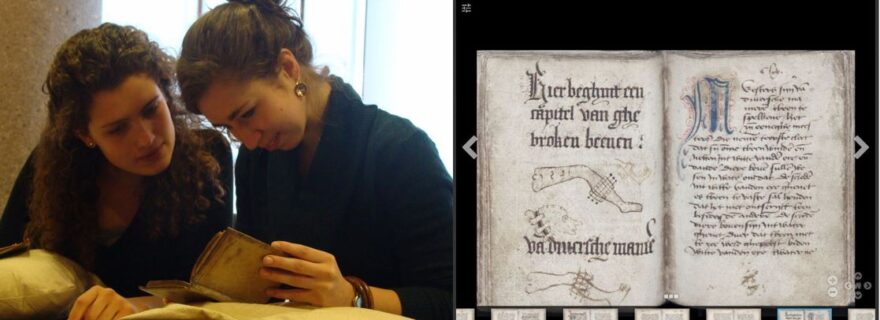

For students who choose to immerse themselves in the Middle Ages, it is important to encounter the primary sources that lie at the basis of their secondary literature and editions.

Regardless of whether they focus on medieval history, art history or literature, students should try and reach beyond their text books and readers, their introductions and abstracts. Viewing an old manuscript in a quiet library room is not unlike hearing Gregorian chant or polyphony in the acoustics of a Gothic church, for it can bring you back centuries ago in a wink. For a moment you may feel the presence of the past, the ‘historical sensation’ pointed out by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945), still famous for his book Autumntide of the Middle Ages.

Hopefully the students have teachers with the right presence of mind, who can lead the way to a library with historical special collections. Leiden University Libraries is such a library. Starting out more than four centuries ago, it has built a substantial collection of medieval manuscripts, comprising about 1800 codices and 1000+ fragments, most of them available for research and education. Scholars, teachers and students are most welcome to use them in our Special Collections Reading Room and lecture rooms on working days (9 a.m. until 5:30 p.m.).

However, such a library is not always close at hand, nor (sadly!) might there be enough time in a bachelor or master course to visit a special collections library. So, what is the next-best thing to viewing manuscripts on site?

View them online.

The last fifteen years have seen extensive digitisation activities by heritage institutions and most of the digital images they created are accessible on the internet – where geographical distances and opening times of repositories are non-existent.

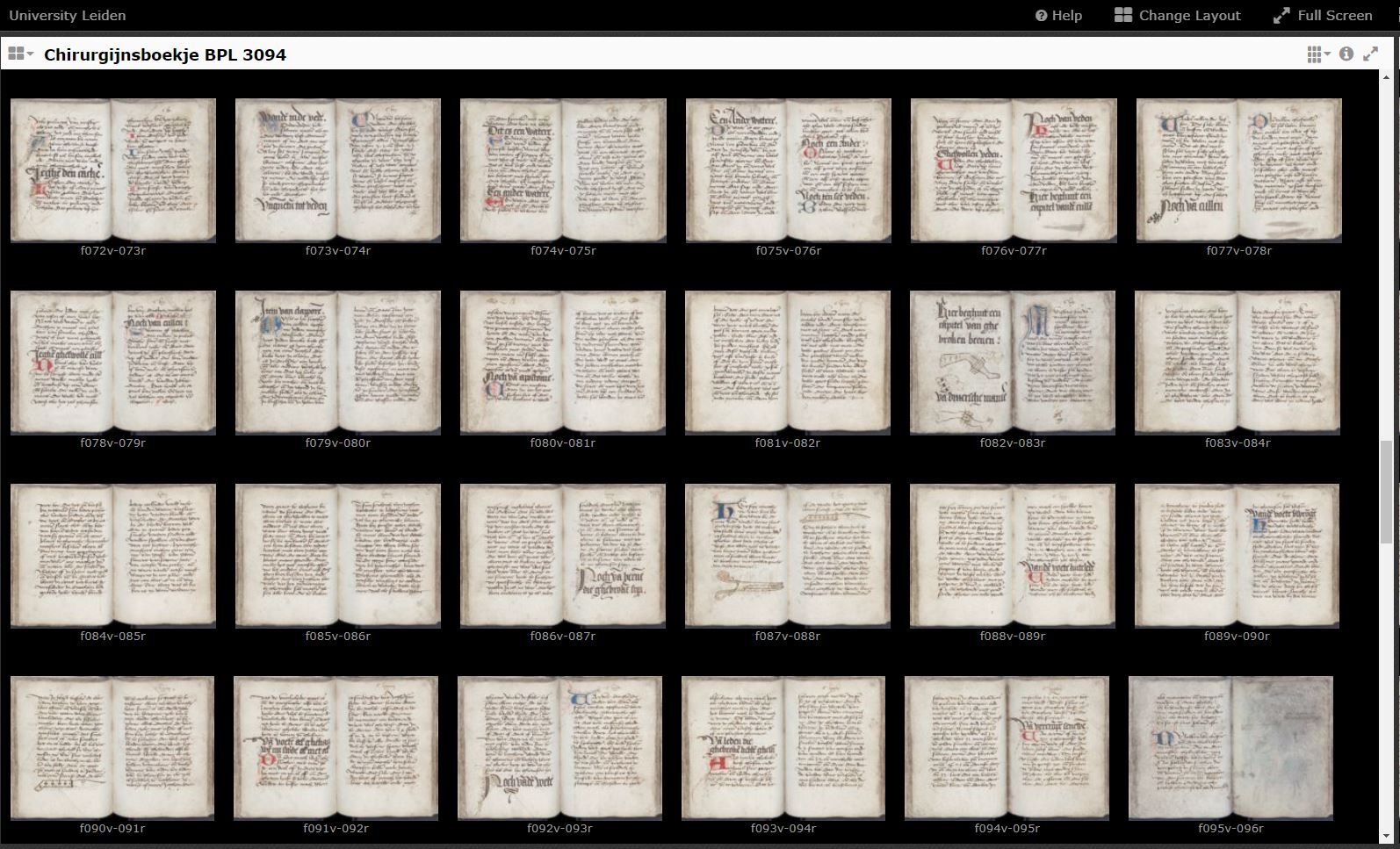

Digital Collections, Leiden’s image repository, contains 500+ digital facsimiles of medieval manuscript books. In October 2020 a new technique (IIIF) was implemented in Digital Collections, which enhances the viewing experience for a single manuscript and also enables comparison of two or more manuscripts in the same session – even when those manuscripts are part of different repositories. The IIIF manifests that have been added to the metadata of the manuscripts offer new opportunities in combining the viewing experience with contextual information.

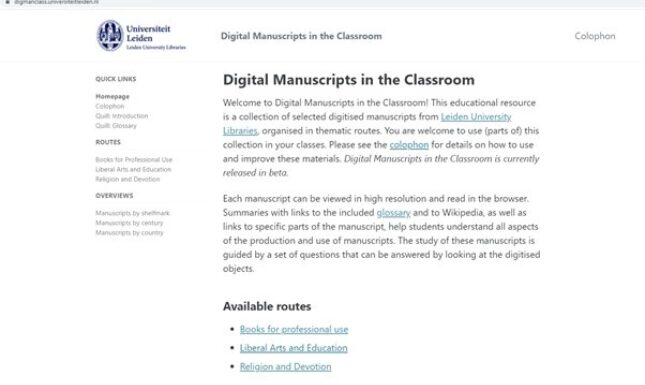

Such is the case in a new website: Digital Manuscripts in the Classroom – the result of intensive collaboration between faculty staff and library staff of Leiden University.

Digital Manuscripts in the Classroom is an initiative of Erik Kwakkel, former Scaliger Professor at Leiden University. The website provides a means to integrate medieval manuscripts in the classroom through short introductory texts aimed at non-experts. Integrated questions prompt students to examine certain aspects of the manuscripts, which they can view in digital form, using the separate window at the top of each web page.

All manuscripts presented on the website were selected from Leiden’s Special Collections by Erik Kwakkel and digitised by library staff, thanks to funding made available by the then Rector Magnificus of Leiden University Carel Stolker. The website was designed and realised by the library’s Centre for Digital Scholarship.

At this moment three ‘educational routes’ (containing 24 manuscripts each) cover the following subjects: Books for Professional Use; Liberal Arts and Education; Religion and Devotion. Hopefully other subjects can be added in due time, with the help of teachers and students.

Digital Manuscripts in the Classroom also incorporates Quill, a former website about particular aspects of medieval book production – created in 2014 by Erik Kwakkel (texts) and Giulio Menna (photos). The Quill information is reshaped into two webpages Quill: Introduction and Quill: Glossary.

On second thoughts, I must confess that the question mark in the title of this blog post presupposes a false dilemma. For most users seem to prefer viewing manuscripts both on site AND online. The physical contact with old books has the advantage of communicating the sensation of holding the Middle Ages in your own two hands. Furthermore, it can be necessary to analyse the materiality of the book. On the other hand, digital contact can last as long as you like, way past opening hours of any library, with no risk of damage or wear to the manuscript (which is good news for future generations of users) and with ample opportunity to zoom in on the details of your choice. So, enjoy the best of both worlds!