Medieval love stories and morality in text and image: 'Der minnen loep' by Dirc Potter

The Dutch poet Dirc Potter (1370-1428) aimed to teach men and women about morality in his love treatise 'Der minnen loep'. His ideas about love were innovative and kind of unusual at the time, which is only one of many reasons why it deserves a closer look.

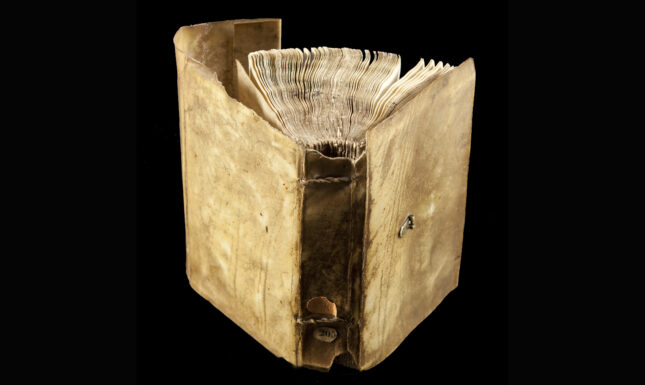

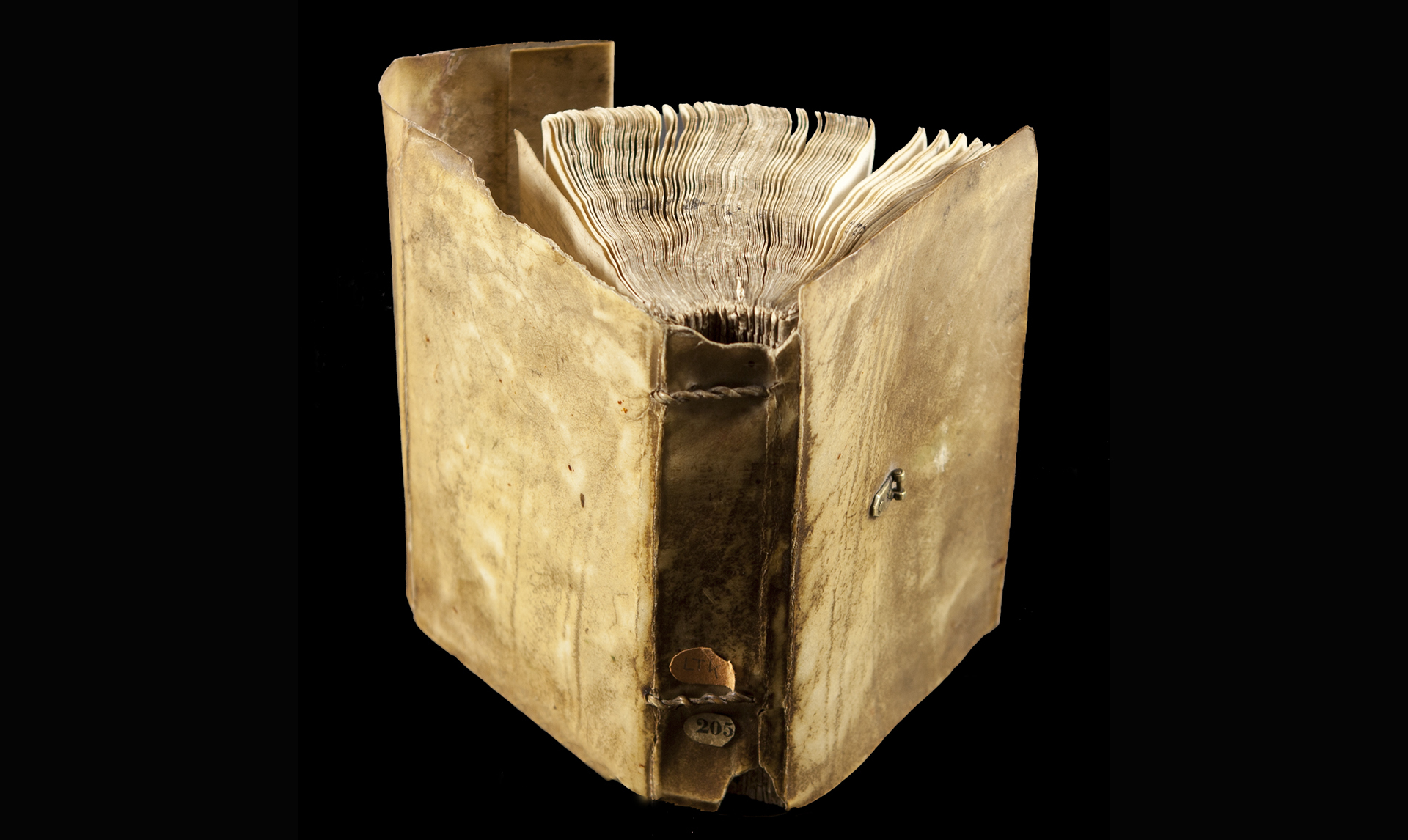

Potter clarifies his beliefs about what love should be with 60 short love stories written as didactic poems. His work is divided into four books, in which he discusses ghecke minne, goede minne, ongheoerlofde minne, and gheoerlofde minne [Strange love (rash love), Good love (from courtship to intimate contact), Illicit love (incest, homosexuality, and rape) and Permissible love (coïtus, only for married couples)]. Der minnen loep was handed down in two manuscripts. One of them, the The Hague manuscript (KB 128 E 6), has traditionally been the source for bibliological research and is, to this day, seen as ‘the better one’. This might be because the Leiden manuscript is quite small and, really doesn’t look like much. As a result, little research has been done into the Leiden manuscript (LTK 205). Well, don’t judge a book by its cover, because the Leiden manuscript is certainly as interesting as the The Hague volume, if not more so. Here’s why.

While the Hague manuscript is one big chunk of text with not much of an indication of where one story or poem begins and the other ends, the stories in the Leiden manuscript are clearly separated. Several methods were used to structure the text.

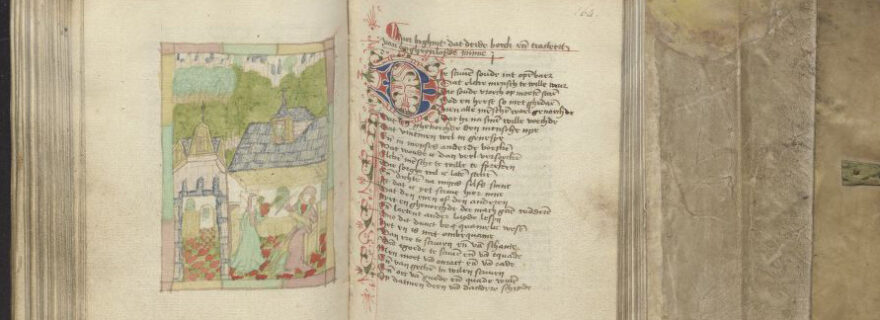

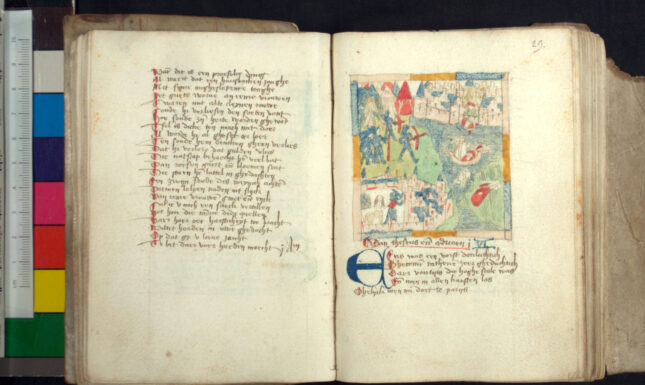

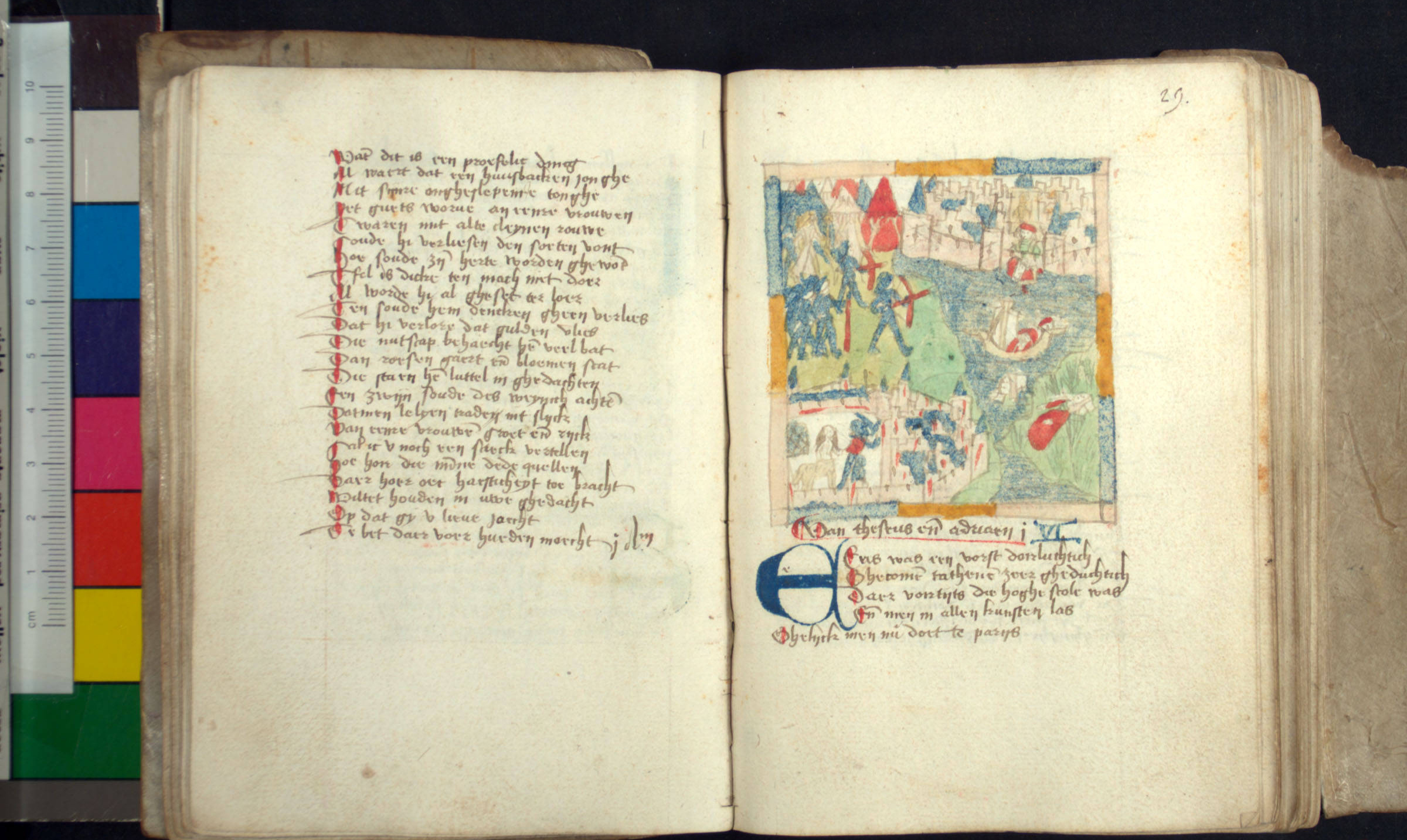

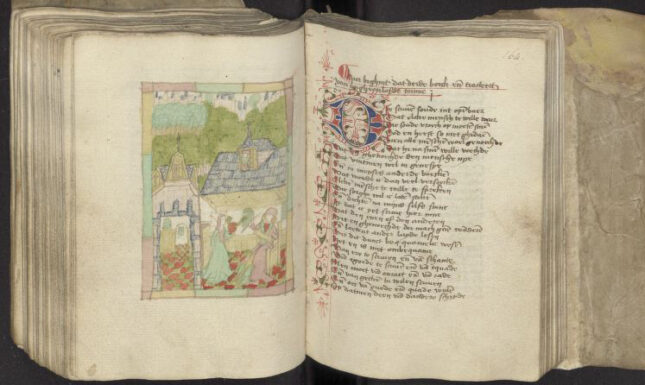

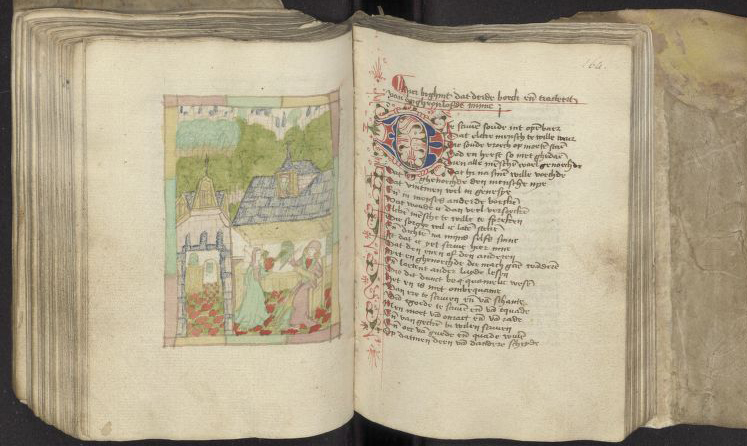

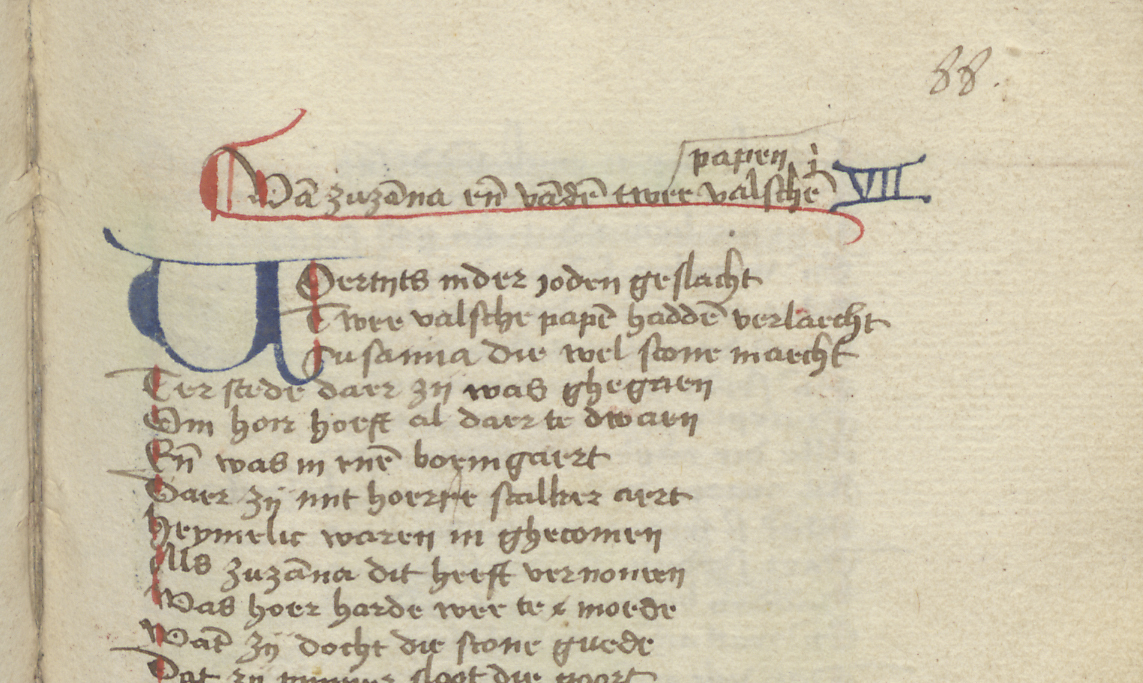

First, the Leiden manuscript features drawings with every love story. One must admit, the images look primitive and are not fancy at all, but they are nevertheless images. There are 52 images in total, with one image missing because the page has been ripped out. The images show key elements of the story that follows and were probably added to support the text.

Each book is introduced with a prologue, written from the perspective of the narrator and a large image covering the whole page on the left. Two of these large images show a man who looks a lot like the poet, Dirc Potter. How can you tell? Well, there’s one other image of Dirc Potter that we know of, in a manuscript of his other work, Bloeme der doechden. The man in the drawings in Der minnen loep looks very similar. This probable portrait of the author makes the Leiden manuscript more special.

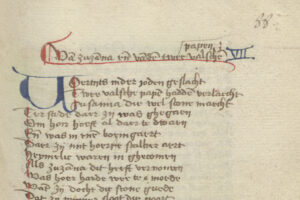

The Leiden manuscript doesn’t just contain images, every story also features a title and a chapter number. The titles contain the names of the characters involved in the story. When you look closely at the titles, you can see that in some cases, the ink of the title runs through the image. This indicates that the titles were added after the images had been drawn and that the work was done in stages: first the text, then the images, and then the titles.

The chapter numbering, too, is very interesting. The roman numerals are drawn adjacent to the titles with blue or red ink, which looks like the same ink used for the initials. This shows that the chapter numbers were added later, along with the initials. But here’s the interesting part: there’s no index to be found. Why number the stories without adding an index? Maybe there was a bigger plan for this manuscript, as its structured layout really lends itself to an index.

This is not the last question raised by the numbering, however. One might expect that numbered stories might be placed in the right order, but in book two, the numbers of the stories are not in sequence, in contrast to the other books. Apparently, someone thought a different order would be better. It is also quite peculiar that the sequence in book two of the Leiden manuscript was also applied in the Hague manuscript, while the The Hague volume is supposed to be older than the Leiden manuscript.

It’s possible that the Leiden manuscript was copied from a different manuscript altogether, to serve as a pocket edition for personal use. This would explain the primitive drawings and the small size of the manuscript. It does, however, not explain the numbering and the sequence of the stories. More likely is the hypothesis that the Leiden manuscript was made to act as an example for a larger, possibly more luxurious manuscript. This explains the fact that the chapter numbers are not in the proper sequence because they show how the correct order should be for the next manuscript. Therefore, the Leiden manuscript can be seen as a rough draft. This explains why the images look quite basic, the absence of an index despite numbered stories, and why the chapter numbers in book two are out of order. It’s because the Leiden manuscript is probably a model for something bigger and more impressive yet to be delivered.

With this new knowledge the Leiden manuscript looks a lot more interesting now, doesn’t it?

About the author:

Annelynn Koenders followed the Nederlandse taal en cultuur Bachelor's programme at Leiden University and is currently following the Book Studies Master’s at the University of Amsterdam and the Older Dutch literature Master's at Leiden University.

Further reading:

- Text edition of the The Hague manuscript.

- Research into a third Der minnen loep book.

- Research into Der minnen loep by Fons van Buuren.