Leiden dissertation 1742: “slavery not against the Bible”

The story of Jacobus Capitein, a former slave advocating slavery.

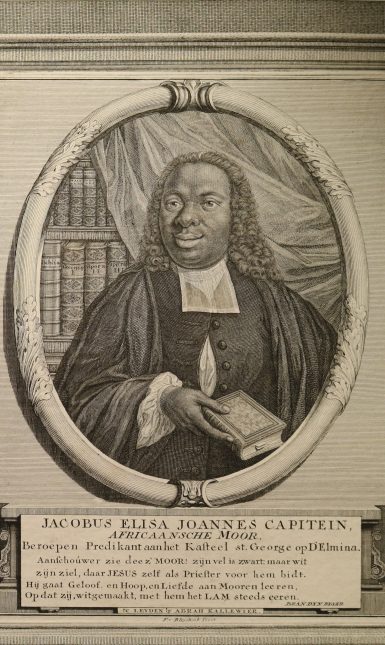

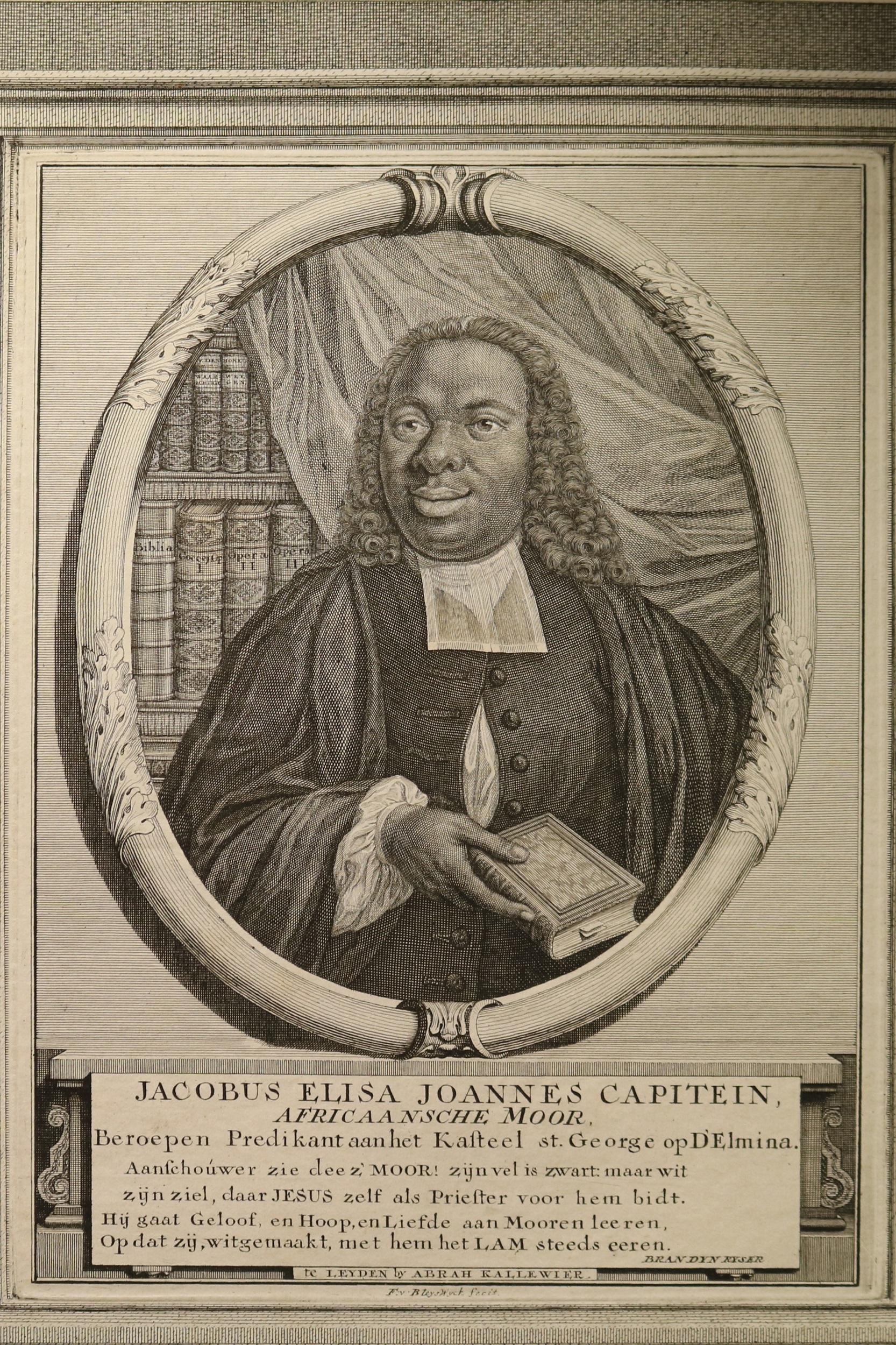

From 1612 onwards, the Dutch operated from some ten fortresses along the Gold Coast (now Ghana), from which slaves were shipped across the Atlantic. It is estimated that the Dutch were responsible for 5-7 per cent of the Atlantic slave trade, or some 550,000-600,000 Africans. Connected with this trade is the peculiar story of a small boy from Ghana in the 18th century. His abductor, the slave trader Arnold Steenhart, named this boy Jacobus Capitein, in honour of the master to whom he was subsequently presented as a gift, Captain Jacob van Goch.

Capitein was born about 1717 and was captured by Steenhart when he was approximately seven years old. The young boy spent two years in Ghana serving Van Goch and was then put on a ship that sailed from Elmina on 14 April 1728 to the Dutch city of Middelburg. When he set foot on Dutch soil on 25 July that year, Capitein's status immediately changed: the slave boy became a free man because slavery did not exist within the Netherlands. From Middelburg, Capitein went to The Hague where he lived in Van Goch's house for several years, taking classes at the Latin School there, learning the catechisms from the Reverend Johan Manger and preparing for university. He was baptised in 1735 before registering at Leiden University in 1737.

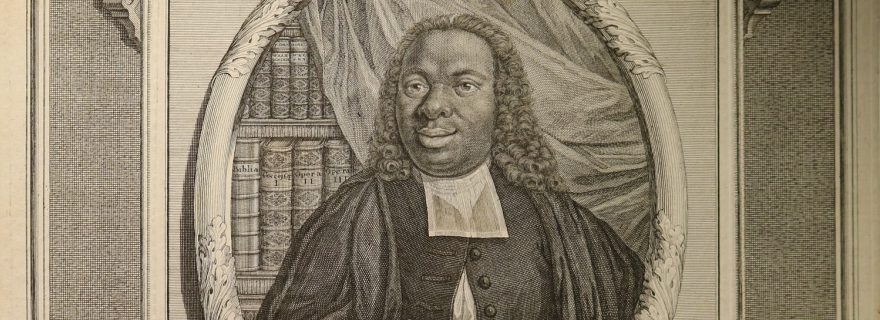

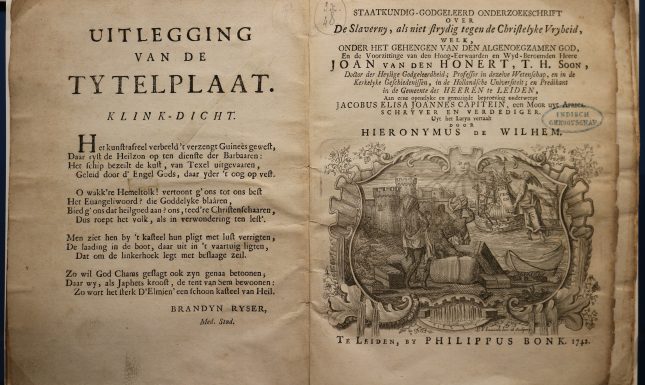

Capitein is famous for a booklet he wrote in 1742. As a former slave, he held that slavery was not against the Bible and, indeed, argued this point in his PhD defence at the university on 10 March 1742: Dissertatio politico-theologica de servitute, libertati christianae non contraria. The text was certainly written by Capitein, though the subject may have been suggested by the chair of the dissertation committee, Professor Johannes van den Honert.

Debates about the abolition of slavery had been going on in the Netherlands for decades. Capitein was just a pawn in this game: a former black slave advocating slavery. A better opponent of the abolitionists could not be found. When I tell students or visitors to Leiden about these events, I can’t help but be deeply touched by the cruelty of this story. But it isn’t finished yet.

Capitein’s dissertation was successful, and the Dutch translation had four editions in one year. A laudatio (celebration) appeared in print with more than ten praise poems by the theologians Hieronymus de Wilhem, Gerardus Kuypers and others. O eer van 't Moorenlant! (O respectable from the land of the Moors!), was the dedication from his university friend Brandijn Rijsen. Capitein toured the Netherlands and two of his sermons (in Muiderberg in May 1742 and in Ouderkerk in June 1742) were also published.

Brandijn Rijsen, whom he had met while a student at Leiden, had already signalled his intention in the foreword to Capitein's dissertation: See this Moor, his skin is black, but white his soul ... He will bring faith, hope and love to the Africans, so they will, whitened, honour the Lamb, together with him.

In July 1742, Capitein sailed to Elmina to bring God's word to the heathens there. He tried hard for more than four years but he was not taken seriously by the Dutch in Elmina, who did not want to be lectured on their moral laxity and their not-so-very Christian behaviour, or by the Akan people in West Africa – although he initially had some success at the small school he established there.

Capitein translated the Ten Commandments and the Lord's Prayer into the local Mfantse language and the work was published in 1744. He used these texts to instruct his pupils in Africa. However, he was rebuked by his superiors from Amsterdam for leaving out the fourth Commandment, which stipulates that servants also had to rest on the Seventh Day. The Classis probably did not understand that Capitein explicitly omitted that part so as not to generate “unrest” among the slaves on the Gold Coast. He subsequently appears to have lost interest in new plans he had for another school. He died in February 1747 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

In 1742, Capitein became probably the first African to defend his PhD at a European university. Perhaps, most importantly, he was the first person ever to publish a text in the Mfantse language. In the last two decades, there has been a revival of interest in him so that at least ten books and articles have been published about his life, his theology and ministry and about his translations.

Author: Jos Damen is Head of the Library and ICT Department of the African Studies Centre, Leiden University

(This text is based on: Jos Damen: ‘Dutch Letters from Ghana’. In: History Today, Aug. 2012, p 47-52)