Toleration in the Dutch Republic? Johannes Wtenbogaert and the Remonstrant minority

Johannes Wtenbogaert wrote several letters to his confidant Hugo de Groot about his difficulties as the informal leader of the Remonstrant congregation in the Netherlands in the 1620s and 30s. The letters offer a different perspective on toleration in the Dutch Republic.

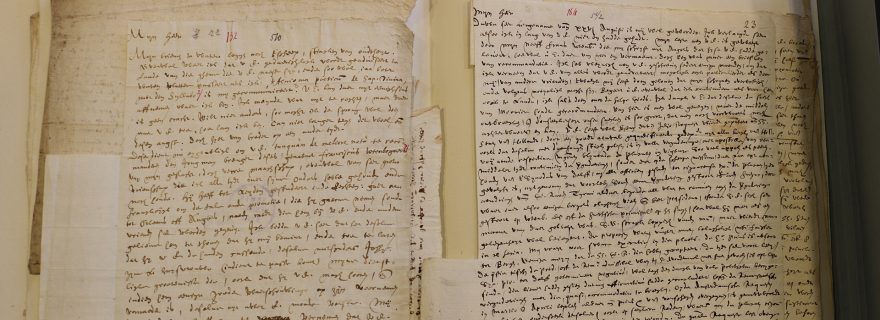

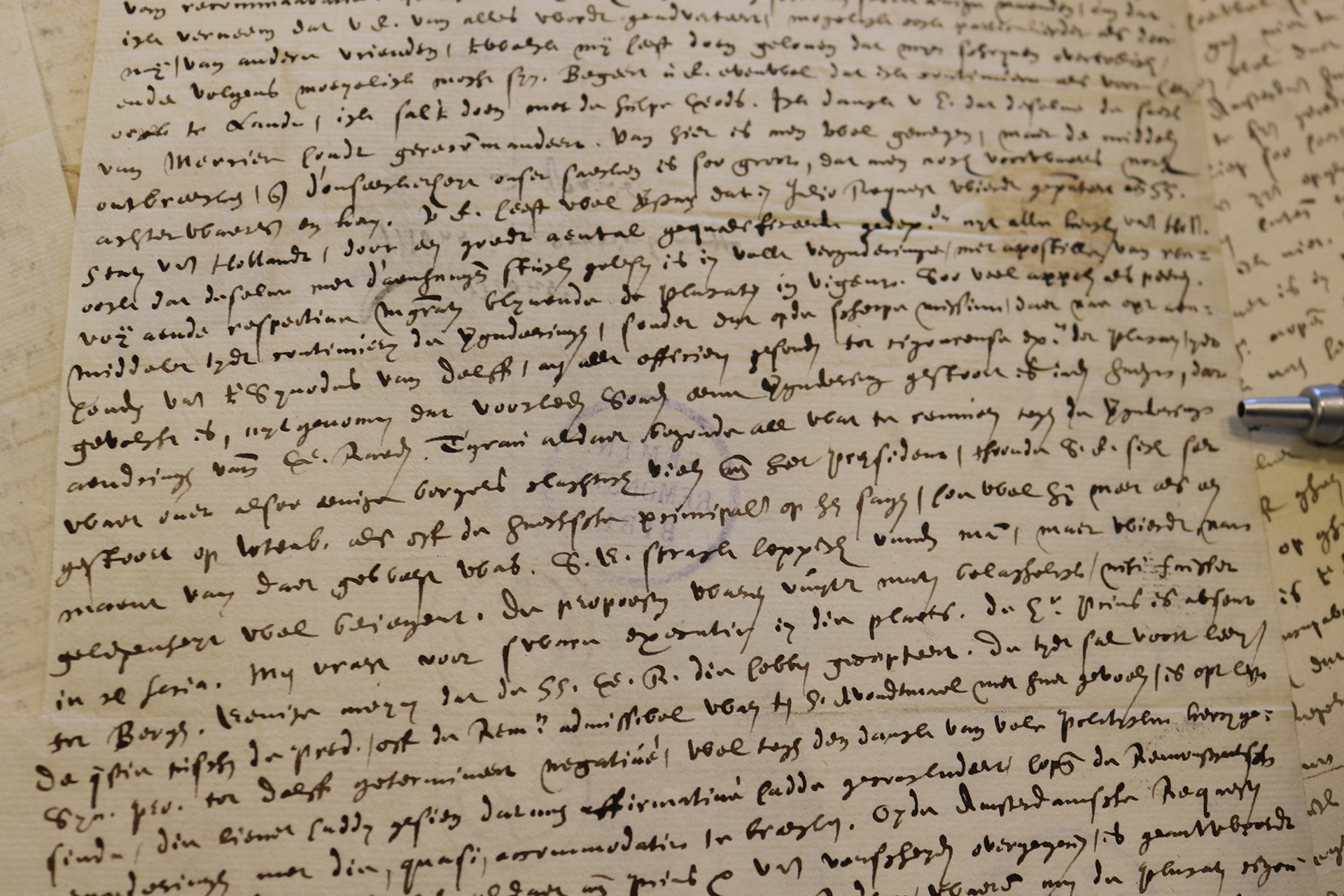

Leiden University Libraries preserves several letters by Johannes Wtenbogaert (1557-1644), the informal frontman of the Remonstrant congregation during the first half of the 17th century. The Remonstrants are a liberal confessional group which had been at the losing end of the so-called Truce Conflicts in the Dutch Republic in the 1610s. They ended up in the position of limited toleration that the Republic extended to confessions other than the official version of Calvinism. Wtenbogaert had lived in exile in Antwerp from 1618 to 1625 when he returned to The Hague and continued working towards the further organisation of the Remonstrant Broederschap ('fraternity', congregation). His letters indicate that the extent of this toleration was, in fact, limited and that the Remonstrants were oppressed both by secular authorities and orthodox sections of the general public.

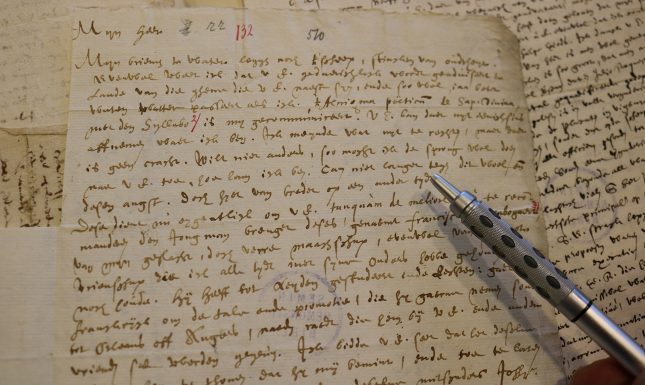

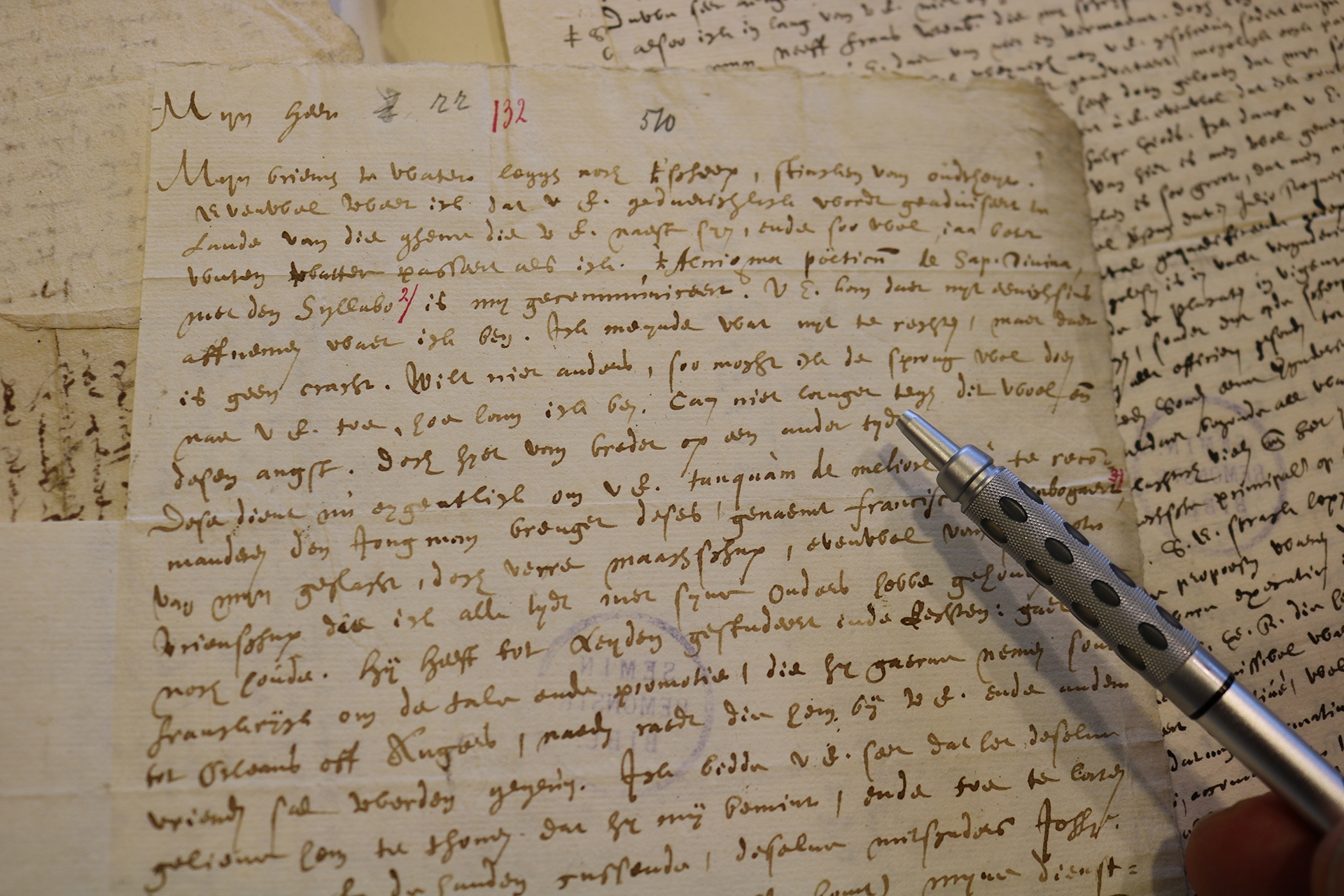

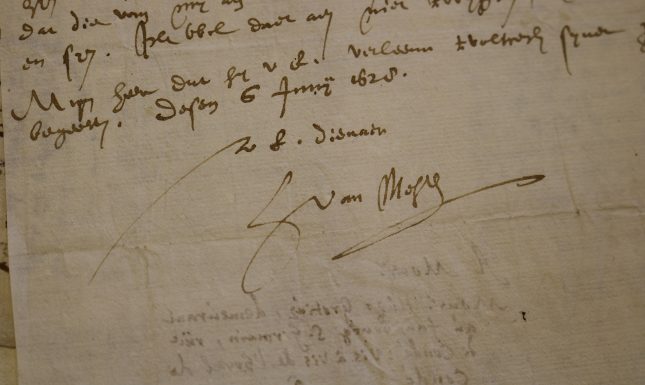

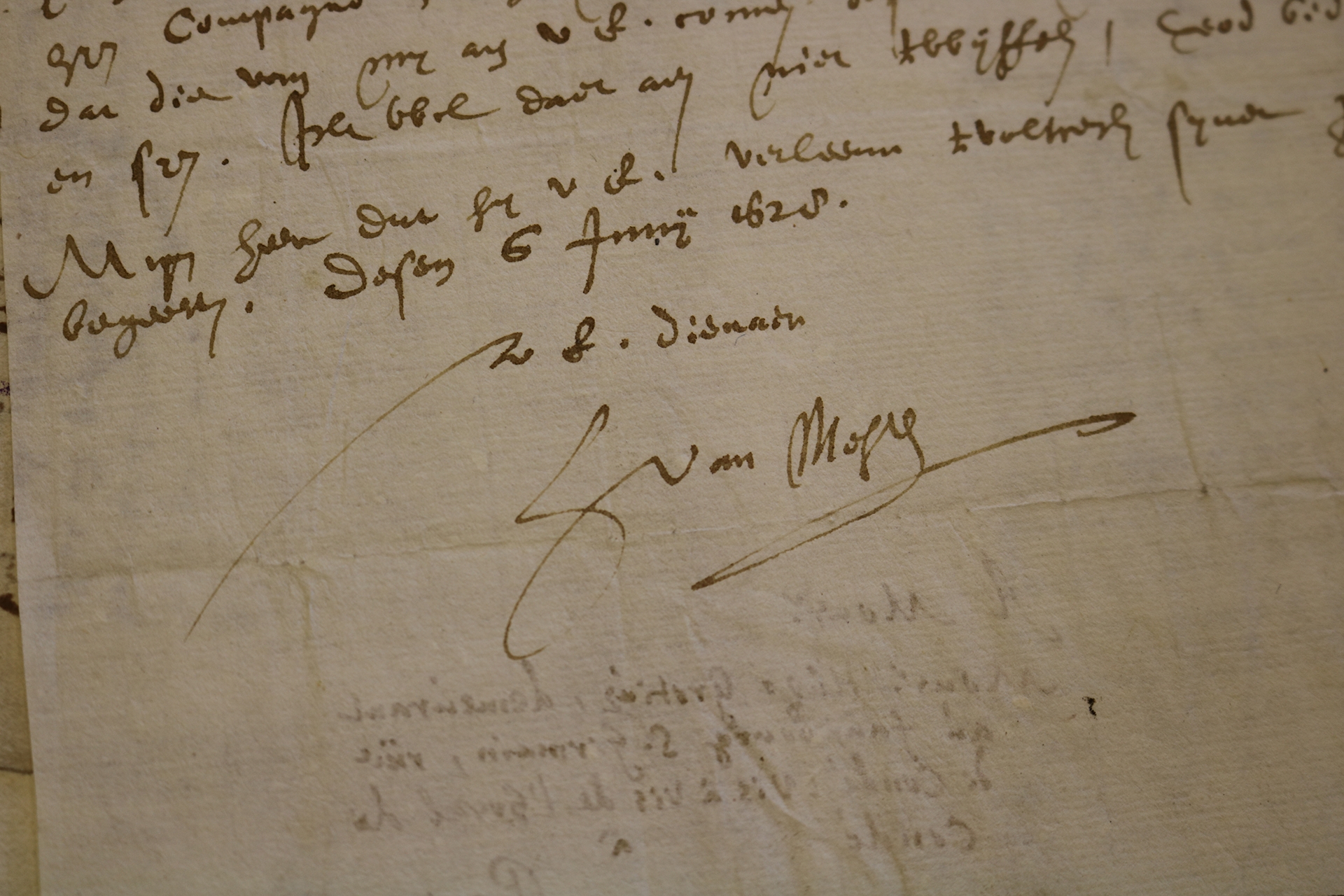

On 6 June 1628 Wtenbogaert writes to his friend and confessional ally Hugo Grotius in Paris (an exile like Wtenbogaert had been):

“My plan was to accomplish one or two things, but I lack the force. Do not think otherwise than that I would travel swiftly to where you are. However much distance I keep though, I can no longer endure this chaos and fear.”

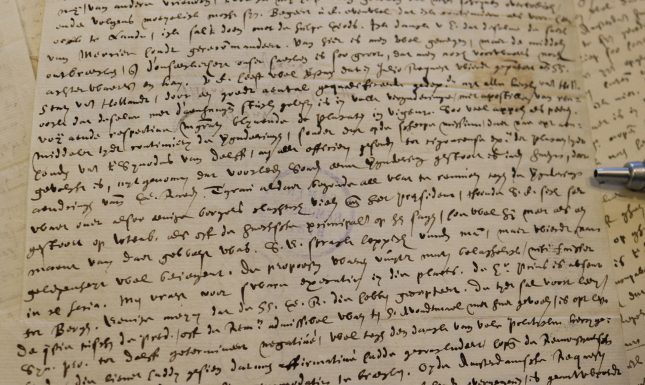

On 21 September he adds:

“Meanwhile the [Remonstrant] gatherings continue without any consequence attached to the sharp instructions [...] that were sent to all the officers to strictly uphold the placards, except that last Sunday a [Remonstrant] gathering in The Hague was disturbed, at the instigation of delegates to the States-General. The populace in that place had already started to grumble against the gathering; and after some citizens had complained to the [council] president, his Excellency directed his anger about it towards me, as if the people of The Hague receive their orders primarily from me [...].”

Passages like these qualify the traditional notion of the Republic as a place of considerable religious and political freedom. They challenge the image of the Republic as a place where people were not forced into conformity with one dominant religion; an image that has its evidence in events of the period and the testimony of visitors. Foreign witnesses marvelled at the unparalleled degree of freedom of religion, conscience and expression that they encountered in the commonwealth of provinces on the North Sea shores. It was expected at the time and is often thought in the present, that from 1625 onwards the position of non-orthodox Protestants in the Republic would improve. In that year Frederick Henry succeeded to the Stadtholderate. He was widely regarded as more liberal than his predecessor Maurice, who had been the decisive factor in the victory of the orthodox faction in the showdown of 1617-1618. Wtenbogaert's anxiety in the fragments above, however, shows that the picture that in the Republic 'other' confessions were allowed to have their gatherings, as long as they kept them invisible and separate from the public sphere, does not tell the full story, at least not for the 1620s. The appearance of threatening crowds must have done nothing to restore Wtenbogaert's and the Remonstrants' peace of mind. The polarisation between the confessional groups which had marked the 1610s had not at all disappeared and could still put bands of people in motion against Remonstrant meetings.

Such qualifications will hardly come as a surprise. In recent years the optimistic image of the Dutch 'Golden Age' has repeatedly been called into question. Does the personal freedom in the Republic still qualify for that label, given how the ethical appreciation of cherished key items in our national past has shifted? Can we apply the word freedom to the historic reality in the Republic in a similar sense to which we use the word for circumstances or ideals in the present?

On the other hand, does it make sense to re-evaluate the past by 21st-century standards which couldn't even be imagined at the time? Be that as it may, an especially worrying perspective in the passages above is the connection they establish between suppression and polarisation. Where polarisation rises, freedom of thought and expression suffer. Wtenbogaert's experiences thus remind us that defending the freedom of expression is incompatible with driving up polarisation in society.

Author: Jan Waszink is a researcher in Intellectual History at the Leiden Centre for Arts in Society (LUCAS). He specialises in political thought and the reception of Greek and Roman classics in the early modern period, especially in connection with the early history of secularisation in Europe. He writes regularly about history in current affairs.

This blog post is part of the thematic programme ‘Oppression and Freedom’, in which Leiden University Libraries (UBL) explores views on identity, relations and the interaction between individuals and groups in the past. The programme includes several exhibitions, workshops and lectures on the subject of oppression and freedom. In addition, there will be blogs, videos and podcasts relating to items in the Leiden Special Collections. More information is available on the Leiden University website.

The letters quoted above are preserved in UBL SEM REM 191.

The original passages:

6 June 1628: “Ick meynde wat uyt te rechten, maer daer is geen cracht. Wilt niet anders, soo mocht ick de sprong wel doen nae U E. toe. Hoe lang ick ben, can niet langer tegen dit woel ende desen angst. Doch hyervan breder op een ander tijdt.”

21 September 1628: “Middelertijdt continueren de vergaderingen, sonder dat op de scherpe missive, daer nae opt aenhouden van ‘t Synodus van Delff, aen alle officieren gesonden tot rigoureuse ex[erciti]e der placaten, yet gevolcht is, uytgenomen dat voorleden Sondach eene vergadering gestoort is in den Hage, door aendringen van de G. Raeden. ‘T grau aldaer begonde all wat te remueren tegen de vergadering, waerover, alsoo eenige borgers clachtich vielen aen den heer praesident, thoonde S.E. sich seer gestoort op Wtenb., als off de Haechsche principalen op hem sagen, hoewel hij meer als een maent van daer geweest was.”

(See also Rogge, Brieven etc. vol. 3.2, no. 510 and 542)

Further reading

E. Cossee, Joost Röselaers en Marthe de Vries (eds), Tolerantie in Turbulente tijden. Johannes Wtenbogaert (1557-1644) en denkers van nu over verdraagzaamheid, Utrecht 2019

H.C. Rogge (ed.), Brieven en onuitgegeven stukken van Johannes Wtenbogaert. Verzameld en met aantekeningen uitgegeven door H.C. Rogge,part 3.2, Utrecht 1873

M. Tolsma, 'Het boek van de Dominee. Rembrandt, Johannes Wtenbogaert en de remonstrantse Kerkorde' in: Face Book. Studies of Dutch and Flemish Portraiture of the 16th to 18th Centuries. Liber Amicorum presented to Rudolf E.O. Ekkart on the occasion of his 65th birthday, Leiden/Den Haag 2012, p. 169-176.

J. Waszink, ‘Oldenbarnevelt and Fishes. Satirical prints from the 12-years Truce’, forthcoming in: History of European Ideas, draft available from: https://www.academia.edu/39784...