Islam in your pocket: A rich yet endangered collection linking Leiden and East Africa

How is one a good Muslim in the modern world? In East Africa, from the 1930s onwards, Islam became portable and accessible: new notions of morality were packed into pocket-size booklets cheaply printed in India. What makes this 982-booklet corpus so unique and fragile?

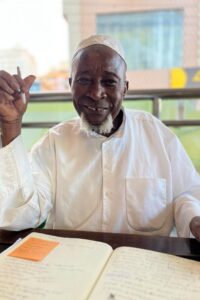

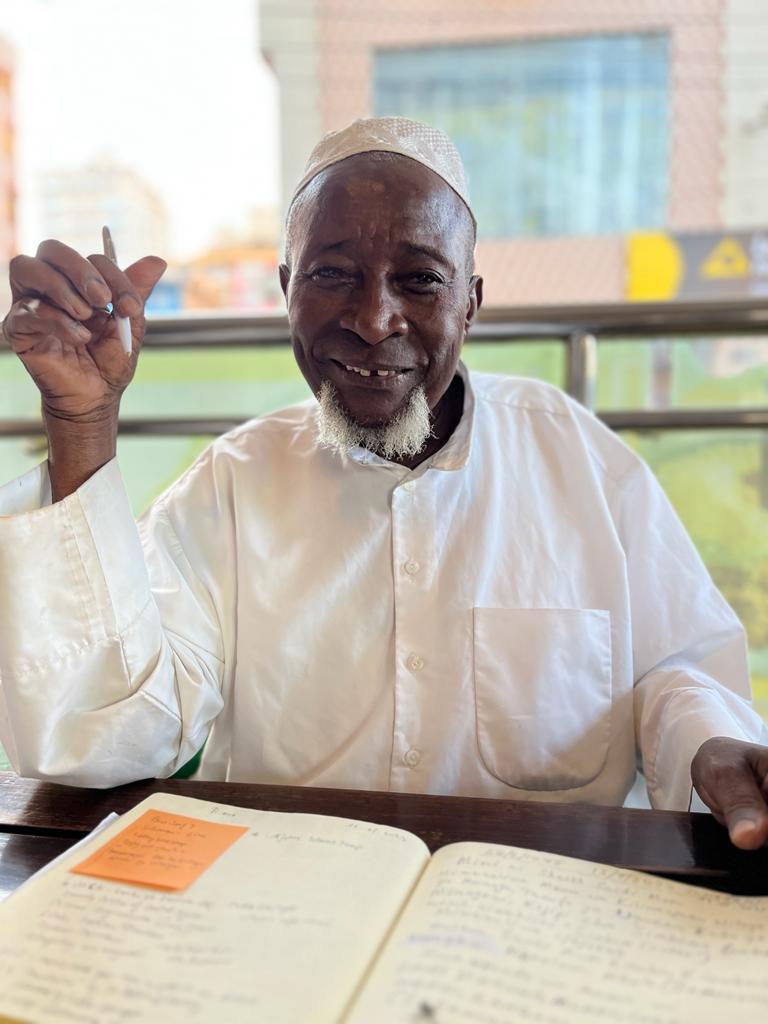

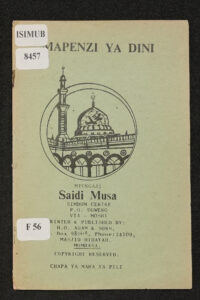

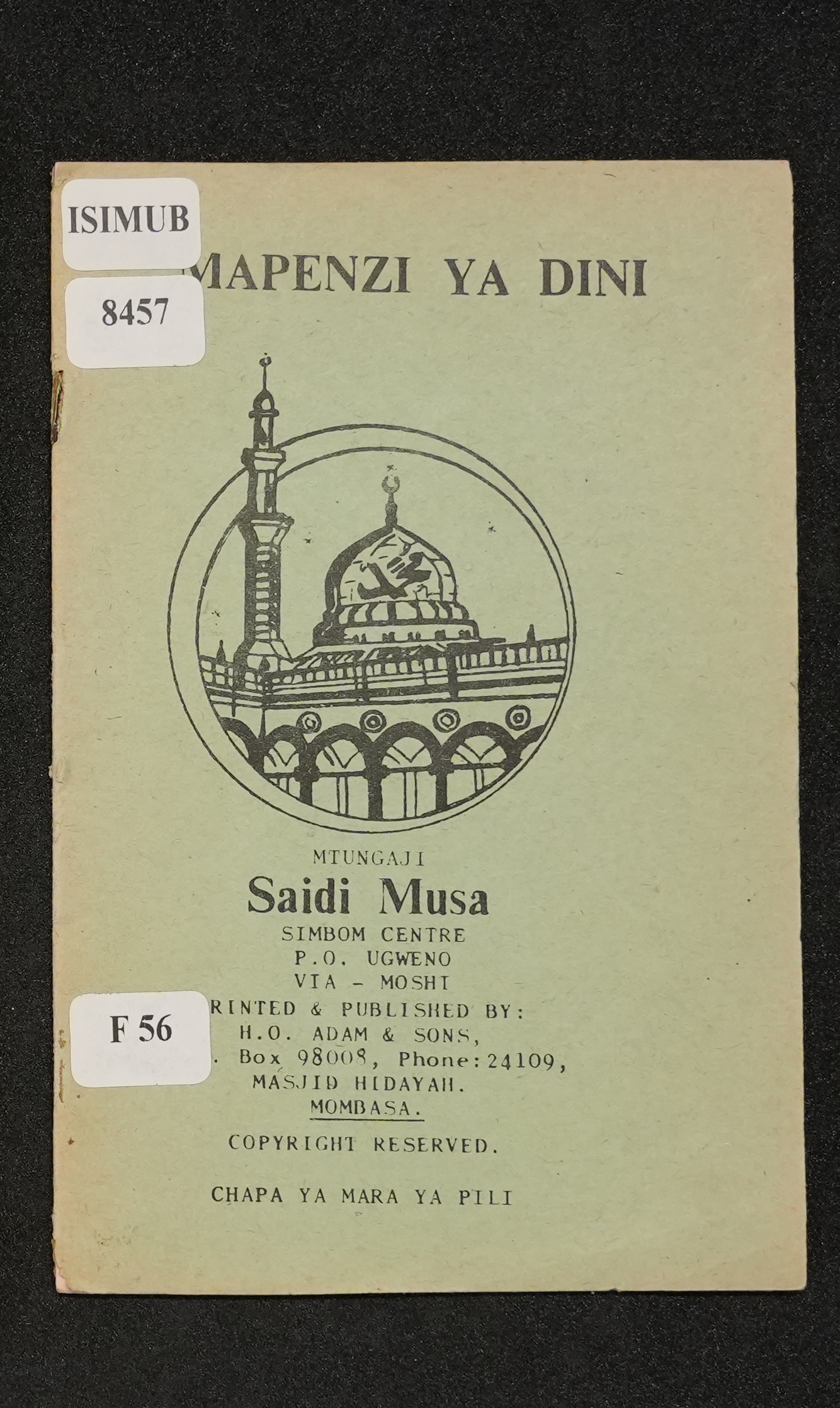

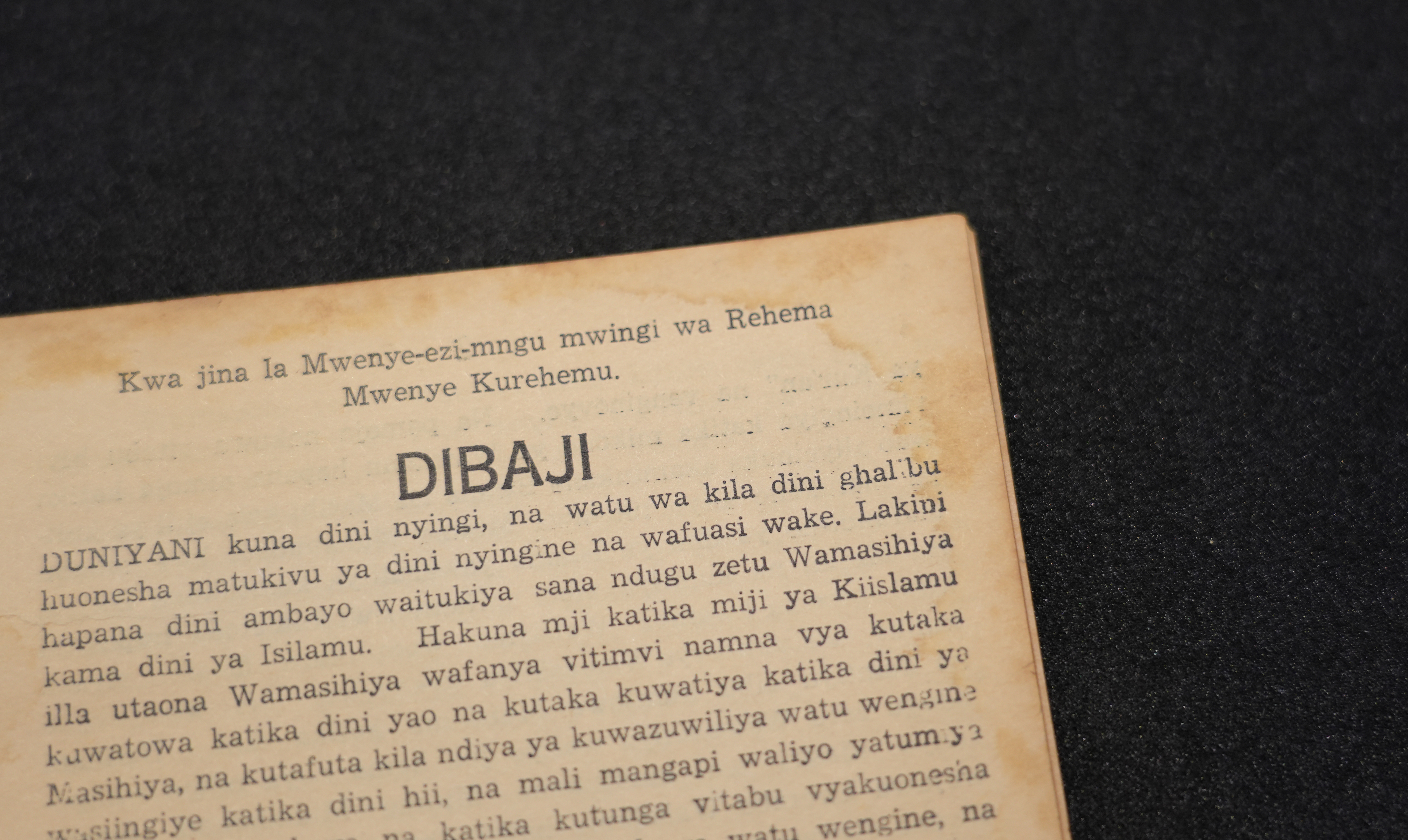

These portable forms of vernacular print Islam were very much the product of transcontinental connections between Swahili authors and booksellers belonging to an Islamic cosmopolis and concerned with educating wider audiences beyond the Arabic-speaking elite. In his work “Love for Religion” (Mapenzi ya dini), contemporary poet and thinker Saidi Musa of Tanzania (Ugweno, 1943) summoned Swahili readers with a sharp “awakening to the readers” (uzindushi kwa wasomaji):

Several Swahili collections are kept at the Leiden University Libraries. As a Swahili specialist with a background in manuscript studies, I have been particularly fascinated by one twentieth-century manuscript-to-print collection commissioned by Jan Just Witkam at the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (see here). According to its inventory list, compiled by archivist Tjikke Vlasma and shared with me, the collection appeared to contain some one thousand titles. In 2019, the records were downloaded with the assistance of Martijn Lens and refined by Ursula Oberst, and we discovered it is larger still: 935 Swahili titles plus 395 in Arabic that altogether represent an extraordinary departure from the majority European Christian religious literature arriving and circulating in East Africa.

A glimpse at the collection shows that the most frequent topics relate to Islamic doctrine (72) and Islamic education (70). A more detailed breakdown provides an overview of the bestselling genres. At the top of the list are books on ritual purity, prayer books and calendars (73). These are followed by books on the Prophet Mohammad (53); texts for learning Arabic and Urdu (51); other prophets’ biographies (43); magic and astrology (43); and women and marriage (45). Other frequent topics are poetry and religious practices (36); social and ethical issues (35); prophets and saints (33); the Qur’an, Qur’anic studies, and translations (38); and Ramadan and fasting (18).

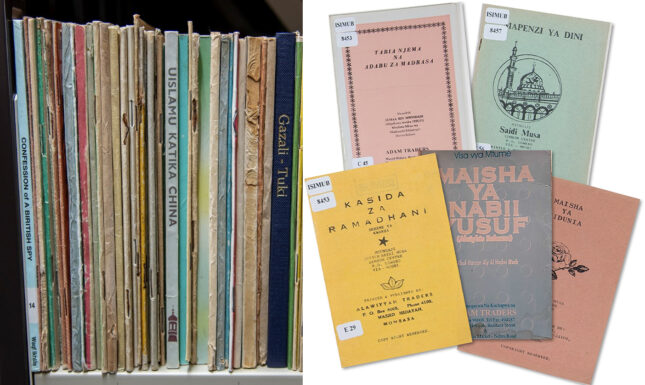

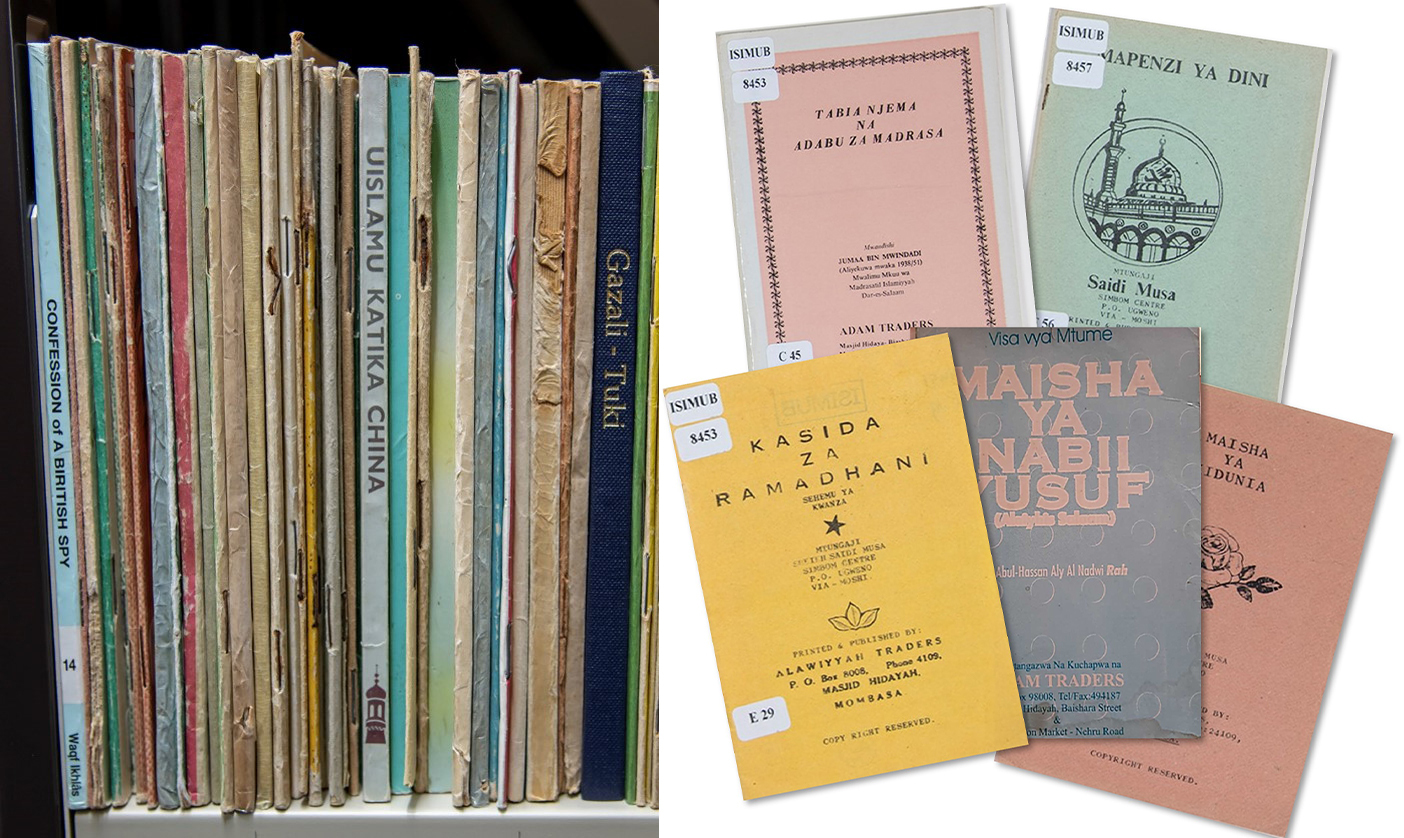

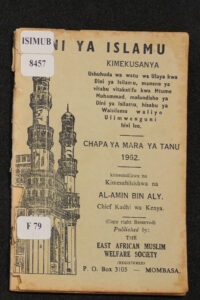

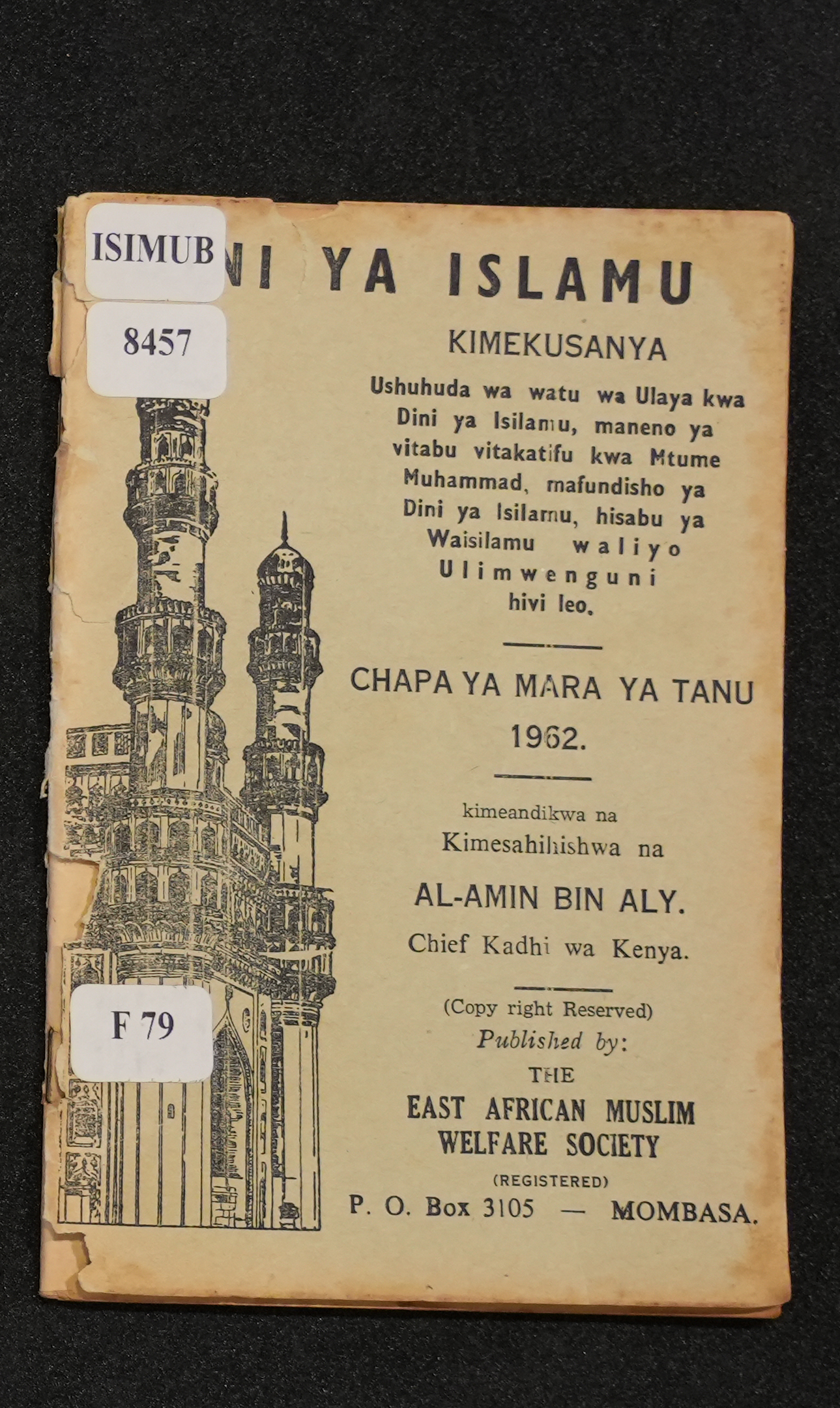

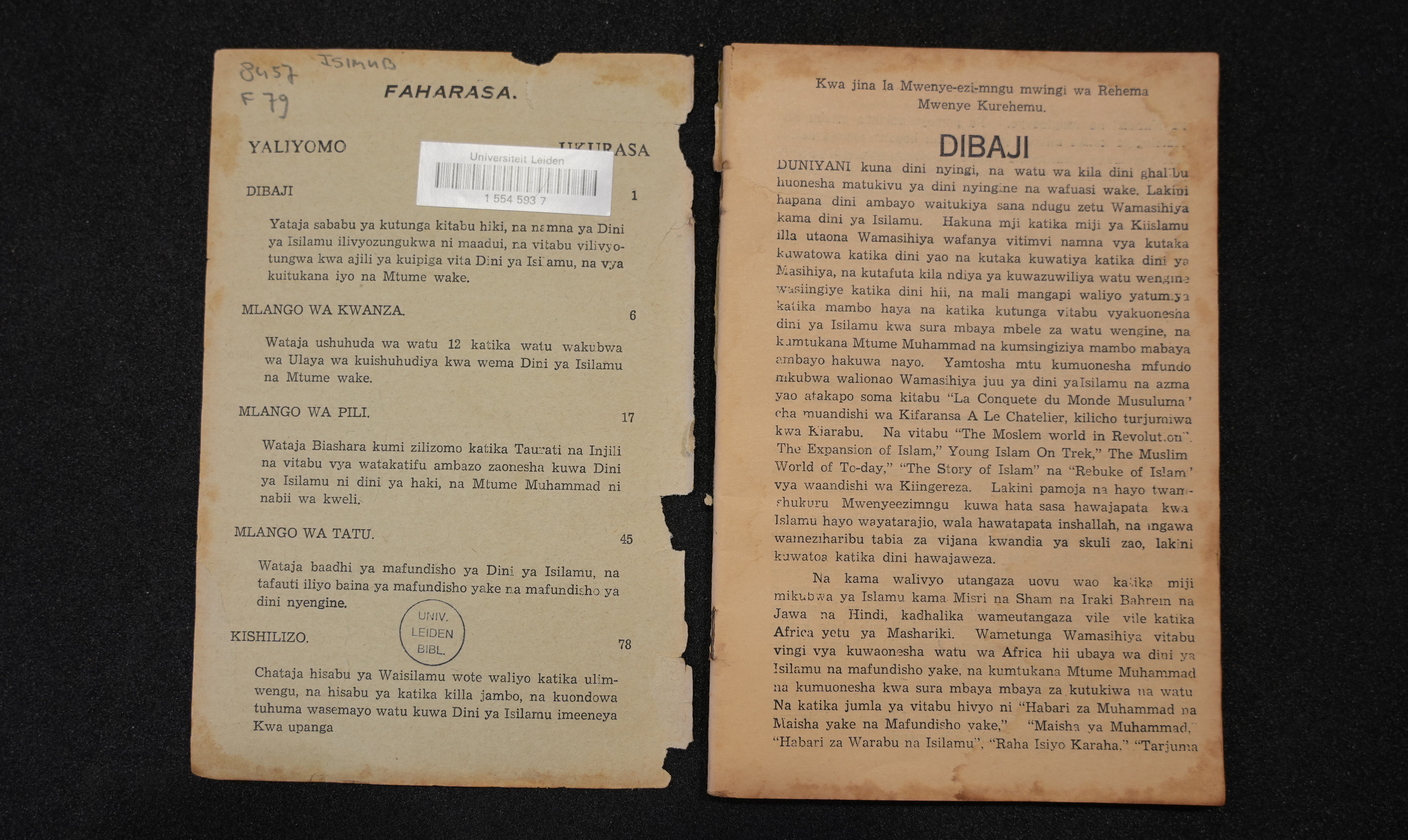

Interestingly, the most commonly used format was 12 x 19 cm, as we see for “The Islamic Religion” (Dini ya Islamu), a Swahili pamphlet collection featuring testimonies on Islam by Christian intellectuals, among whom – to mention only a few – Thomas Carlyle, Laura Veccia Vaglieri, and the French philosopher Voltaire.

The larger 20 x 16 cm format was the most common for disseminating creative adaptations of didactic literature after the ’60s, when poetic booklets would become a mainstay. In a handbook for madrassa pupils titled “Good Manners and Madrassa Etiquette” (Tabia njema na adabu za madrasa) author Jumaa bin Mwin-Dadi mixes prose and poetry in touching on all facets of this topic, even matters of physical cleanliness, as illustrated in the excerpt below:

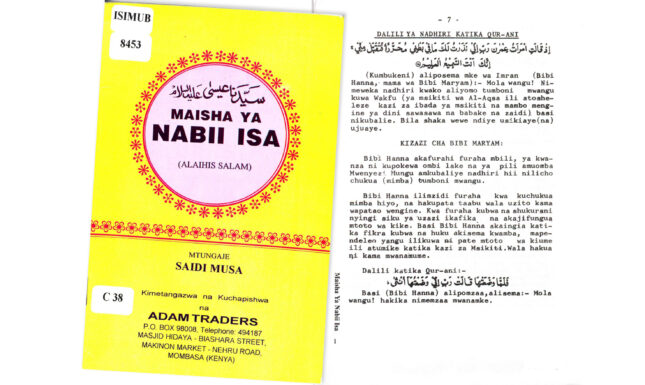

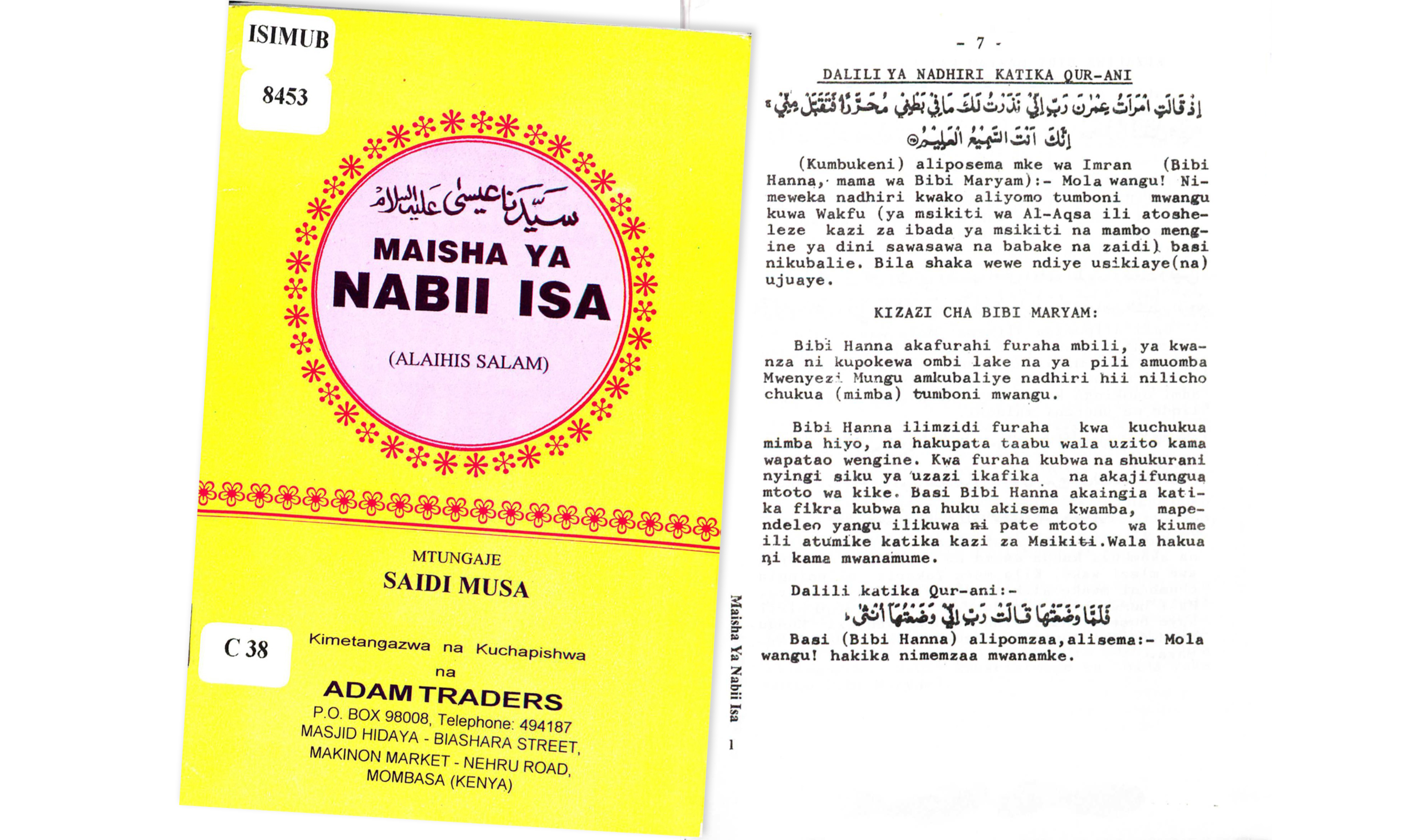

In terms of layout, these booklets also show the early assimilation of Western orthographic conventions and typography, e.g. capitalized letters, punctuation, and above all, the use of Roman script. Yet the Arabic script, specifically in eulogistic formulas such as the basmala (“in the Name of God the Merciful”), remains present. In Saidi Musa’s The Story of The Prophet Jesus (“Maisha ya Nabii Isa”), his teacher Sheikh Abdalla Saleh Farsy (a qadi of Zanzibar who later moved to Kenya) praises precisely this patchwork of Swahili prose text (in Roman script) and verses quoted from the Qur’an (in Arabic script); as he puts it:

Print certainly changed the way Swahili people knew and practiced Islam, yet being cheaply produced on Manila paper from India, this rich collection has also suffered damage from bookworms and age. Digitizing these sources is thus an essential task for bringing the collection to scholarly attention, and will allow students and scholars in the Global North, compelled by the broader debate of decolonizing these archives, to access and study African-language literature.

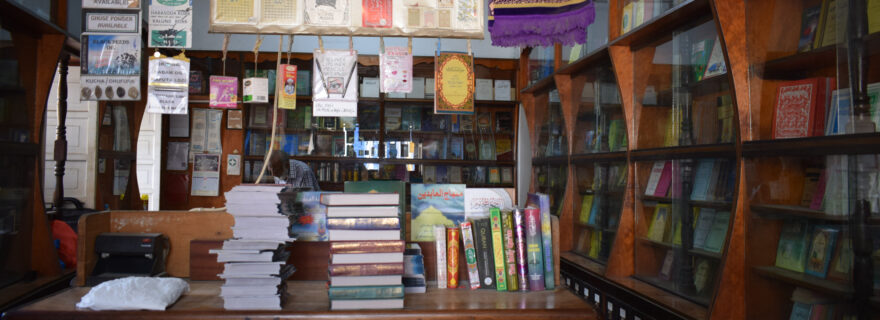

In the framework of the NWO Talent Programme Veni SSH 2021 project “Portable Islam: Swahili Literary Networks in the Indian Ocean,” this collection is being linked to living family-run bookshops and authors in East Africa and India to better contextualize the making of a transoceanic tradition of learning.

______

About the author:

Annachiara Raia is an Assistant Professor at the Leiden Africa Studie Centrum and an interdisciplinary University Lecturer at the Leiden Centre for Arts in Society.

Works cited

bin Aly, A. (1962). Dini ya islamu : kimekusanya Ushuhuda wa watu wa Ulaya kwa dini ya isilamu, maneno ya vitabu vitakatifu kwa mtume Muhammad, mafundisho ya dini ya isilamu, hisabu ya waisilamu waliyo ulimwenguni hivi leo. Mombasa: The East African Muslim Welfare Society (ISIM 8457 F 79).

bin Mwin-Dadi, J. (1997). Tabia njema na adabu za madrasa. Mombasa: Adam Traders (ISIM 8453 C 45).

Bruinhorst , G. C. van de (2001). Islamic literature in Tanzania and Kenya. ISIM Newsletter, 8(1), 6–6.

Damen , J. (2008). The princess bride: How did a Zanzibari princess marry a German merchant–and her library end up in Leiden? Rare Book Review, 35(June–July), 14–15.

Musa, S. (1964). Mapenzi ya Dini. Mombasa: H. O. Adam and Sons (ISIM 8457 F 56).

Musa, S. (ca. 1998). Maisha ya Nabii Isa. Mombasa: Adam Traders (ISIM 8453 C 38).

Further reading

Raia, A. (2022). Easy to handle and travel with: Swahili booklets and transoceanic reading experiences in the Indian Ocean littoral. In M. A. Thumala Olave (Ed.), The Cultural Sociology of Reading (pp. 169–208). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13227-8_7

Lacunza Balda, J. (1989). An investigation into some concepts and ideas found in Swahili Islamic writings. [Doctoral dissertation, SOAS, University of London].