Hitting the streets at the Dies Natalis

The rijjool as part of the Dies celebrations around 1900

In 1946, the Academic Historical Museum in Leiden acquired a series of forty watercolour drawings, depicting student life in Leiden at the beginning of the century. The drawings were made by an unknown illustrator – he signed the drawings with ‘V-’. Based on some of the scenes depicted, the drawings can be dated between 1905 and 1910. In the series, we follow the life of a Leiden student outside the lecture halls, from his arrival in Leiden as a groen – a student who has not yet been hazed – via his membership of the Leidsch Studenten Corps – the main fraternity in Leiden at the time – and a number of other associations, up until the moment he defends his PhD.

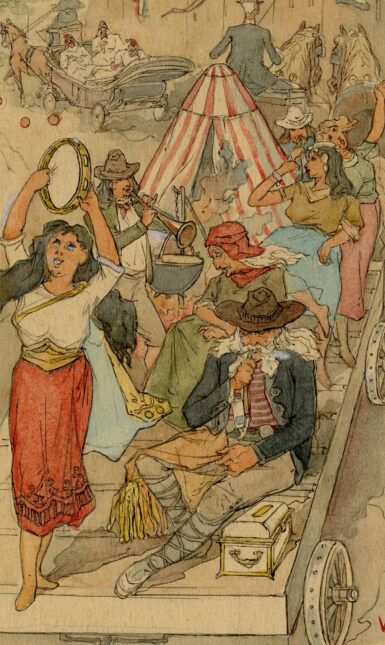

The drawings depict student life not necessarily as it was in reality, but rather as the students believed it should have been. Most of the drawings have a humoristic undertone and some are even slightly allegorical, like the one in which the goddess Minerva cradles a new student as a newborn (green) baby. The Dies Natalis, the highlight of the Leiden academic year, is also depicted in this series. The drawing titled ‘8 Februari’, however, depicts an unexpected scene for the present day viewer. It doesn't show a procession of professors in their black robes, nor a crowd in the Pieterskerk or the Academy building listening to the Dies-oration, but rather two festive carriages driving through the streets. Four people in white robes sit in the first carriage, while the second one carries a group of seemingly Romani people. What does this scene have to do with the Dies celebrations?

While nowadays the Dies is celebrated almost exclusively by Leiden's academic community - staff, students and alumni - this was not the case in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. ‘Hundreds of flags fluttered in the thin winter air, shone upon by a glorious, uplifting February sun, under whose auspices our august university celebrated its 334th birthday’, could be read in the Leidsche Courant of February 8 1909, ‘There was a great bustle in the streets all afternoon. The Breestraat in particular was full of people, Leiden's citizenry sympathizes with its university: its fame and pride.’

The Breestraat, in particular, was the centre of the celebrating city. This was largely due to the fact that corps students – whose clubhouse was in the Breestraat – provided most of the entertainment in Leiden’s streets. In the evening, a large number of the corps students would ride in torchlit carriages from their clubhouse along an elaborate route through the city to the restaurant where the professors were having their banquet and offer them a so-called serenade. In the afternoon, the first year members of the Leidsch Studenten Corps had their own parade: the so-called rijjool (a ‘riding party’).

This rijjool consisted of various thematically dressed groups. During the most of the nineteenth century, these themes were quite general (the five faculties always seem to have been popular), but around the turn of the century, the themes became more specific, portraying recent news stories. This is what the Leidsche Courant wrote about the 1909 rijjool:

‘There was, for example, Moulay Abdelhafid, Sultan of Marocco, with his retinue. A real camel, ship of the desert, accompanied them. (...) The Steinheil affair was vividly represented and Castro had even come from Berlin.’

Moulay Abdelhafid had become Sultan of Morrocco in August 1908, the Steinheil affair was a high profile French lawsuit against Marguerite Steinheil, starting in November 1908, and José Cipriano Castro was the president of Venezuela, who was overthrown in December 1908, while being treated for kidney problems in Paris and Berlin. Apart from these depictions of news stories, some more general themes also remained popular. The rijjool of 1909 ended with ‘characteristic Romani wagons filled with carnival types', just as depicted in our drawing. It should be added, however, that while the drawing clearly shows men and women on the wagon, in reality all participants were members of the all male Leidsch Studenten Corps.

Just as its bigger – and more professionally organized – counterpart the maskerade, which was organized every five years by the Leidsch Studenten Corps, when the university celebrated a lustrum, the rijool seems to have succumbed to its own success. Each edition, the scenes depicted became more elaborate and the costumes became more professional, which also caused the organization and preparation to take more time and the costs for the participants to increase. Already in 1896, so few freshmen wanted to participate that for a while it looked like the rijjool would not be organized. Although that year the event went ahead, the parades did shorten every year since. After World War II they would disappear from the Dies program entirely.

For our anonymous illustrator ‘V’ this was still unthinkable around 1905-1910. By putting it as a centre piece in his ‘canon’ of Leiden student life, he shows that as far as he was concerned, no other activity embodied (the student-centric side of) Leiden University's Dies Natalis more than the rijjool.

About the author

Erik-Jan Dros is a historian with a special interest in book history and the history of Leiden University. He works as a project manager at Leiden University Libraries (view profile).