Historic protective enclosures from the Middle East

Bindings bear the brunt of usage, as they are made to protect a textblock. To protect the bindings, various book cultures in the Middle East and Africa kept bound manuscripts in bags or satchels. These understudied enclosures often need conservation care, just like the manuscripts they protected.

The previous blog post introduced the idea that material studies and conservation education is part of the conservation of collections at large. The UBL therefore frequently accommodates students in book and paper conservation in the conservation studio. Over the years, a number of students from various universities and countries obtained experience working with materials from the Middle East and Asia. Often, an internship includes a project with a particular focus; a problem demanding dedicated time or an issue requiring a comparative study. A good example is the Islamic slipcase project. A slipcase is a historic protective enclosure that sits somewhere between a bag and a box.

Protective enclosures are fairly common in the book cultures that developed in the tradition of the Coptic codex, the first bookbinding tradition to emerge in the Levant. The use of such a protective container is well-known for Ethiopic manuscripts. They often received a leather bag, which could be used to carry the item when travelling, but the bag had the primary function of storing the book in the home. The bags would be hung on a peg in the wall, in order to keep the manuscripts out of reach of insects or rodents on the floor. The UBL houses nearly 200 Ethiopic manuscripts, and almost half of them still retain their leather bags, which are made in a typical manner that is specifically linked to the Ethiopic book culture.

Sub-Saharan manuscripts were also often kept in a leather bag or satchel, with characteristics by which they can also be identified. In this region, the manuscripts were usually copied on loose leaves, which remained unbound. A primary covering of leather or fabric, often strengthened with boards, was wrapped around the loose stack of leaves, and this bundle was then placed inside a satchel that was usually decorated with embroidery or leather cut-work.

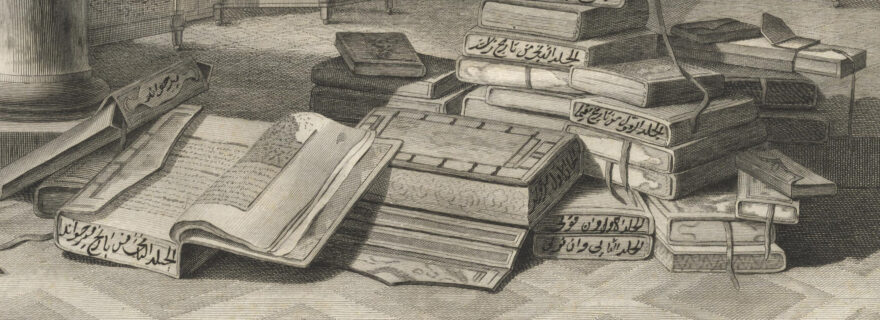

In the Islamic tradition, many bound manuscripts received a protective enclosure as well. Early literary sources mention the use of wooden chests for the Qur’an, and manuscript paintings illustrate that textile bags or envelopes were used from at least the fifteenth century onwards. In the centuries after that, other enclosures were developed as well, and the type that is typically linked to the Ottoman world is the slipcase. They were made and used into the early twentieth century.

The historic enclosures are often not mentioned in catalogues, with the exception of the richly embellished and remarkable ones. Therefore, it is unknown how many historic enclosures have survived, and the lack of these records also hampers the study of these artefacts. The substantial Arabic manuscript collection in Leiden includes a fair number of these satchels, bags and slipcases, although we do not know how many exactly. In terms of conservation, these items also tend to fall between the cracks. When budgets are limited, the available time and means will not be spent on the conservation of the protective enclosures of manuscripts, but solely on the manuscripts themselves. Access to the manuscript actually increases the risk of damage to the enclosure, and slipcases seemed exceptionally prone to damage. Therefore, we were looking for a pragmatic way to preserve them.

When David Plummer, a West Dean (UK) student in book conservation, came as an intern to Leiden in 2018, he was keen to take on the topic of the slipcase issue. Their conservation problems were obvious. The flexible leather sides are frequently torn because of the interactions with the users when they want to retrieve the manuscript from the case, and characteristic features of the artefacts could be lost without preventive measures. In the Arabic manuscript section, we identified thirty-three slipcases, twelve of which are contemporary with their associated manuscripts.

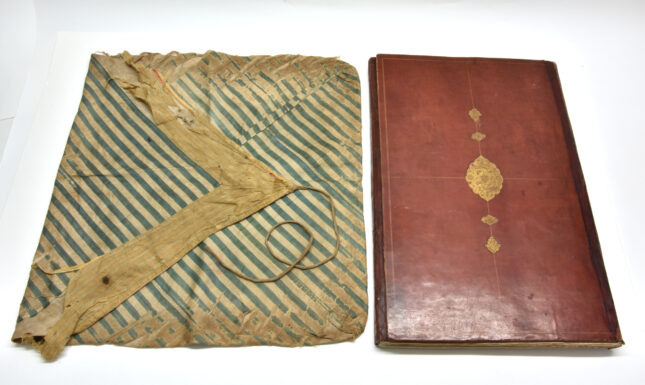

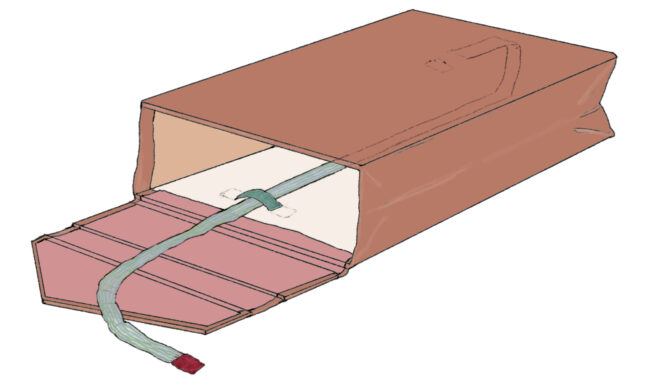

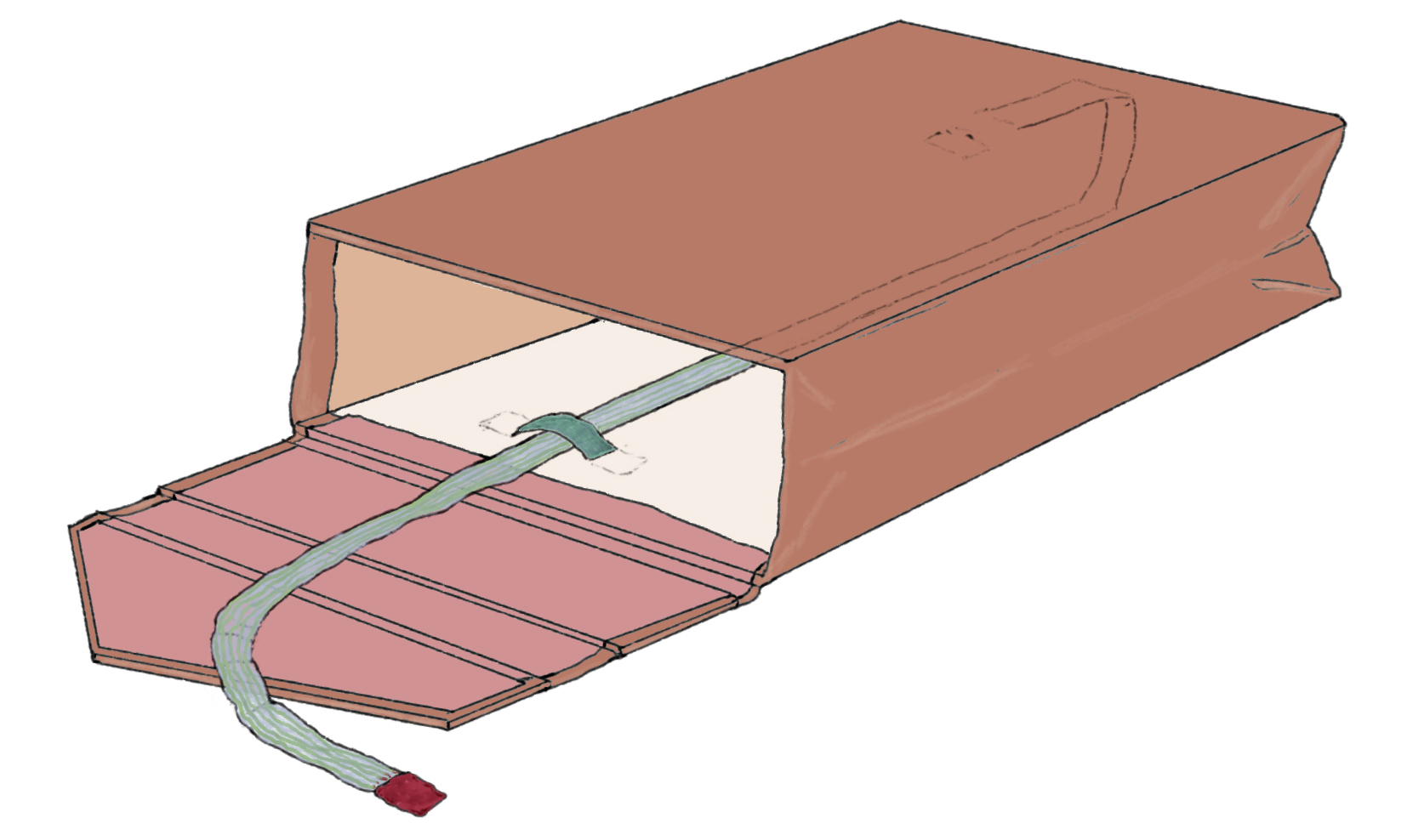

We learned that the quality of a slipcase or the importance of the manuscript it protects can be deduced by the presence of a manuscript retrieval strap. This – often beautifully band-woven – textile strap helps to retrieve the volume from the case, without causing stress on the materials of the case. When the slipcase was made without this strap (a lower-budget version), the manuscript could only be pulled out of the box with combined gravitational and mechanical force. Since this easily forces the ageing materials to tear or break, it is now necessary that the manuscripts are no longer housed in their slipcase, but that the items are stored together in a custom-made box that retains both items available for study. After all, historic enclosures are part and parcel of the objects.

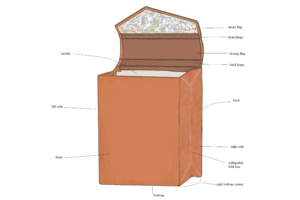

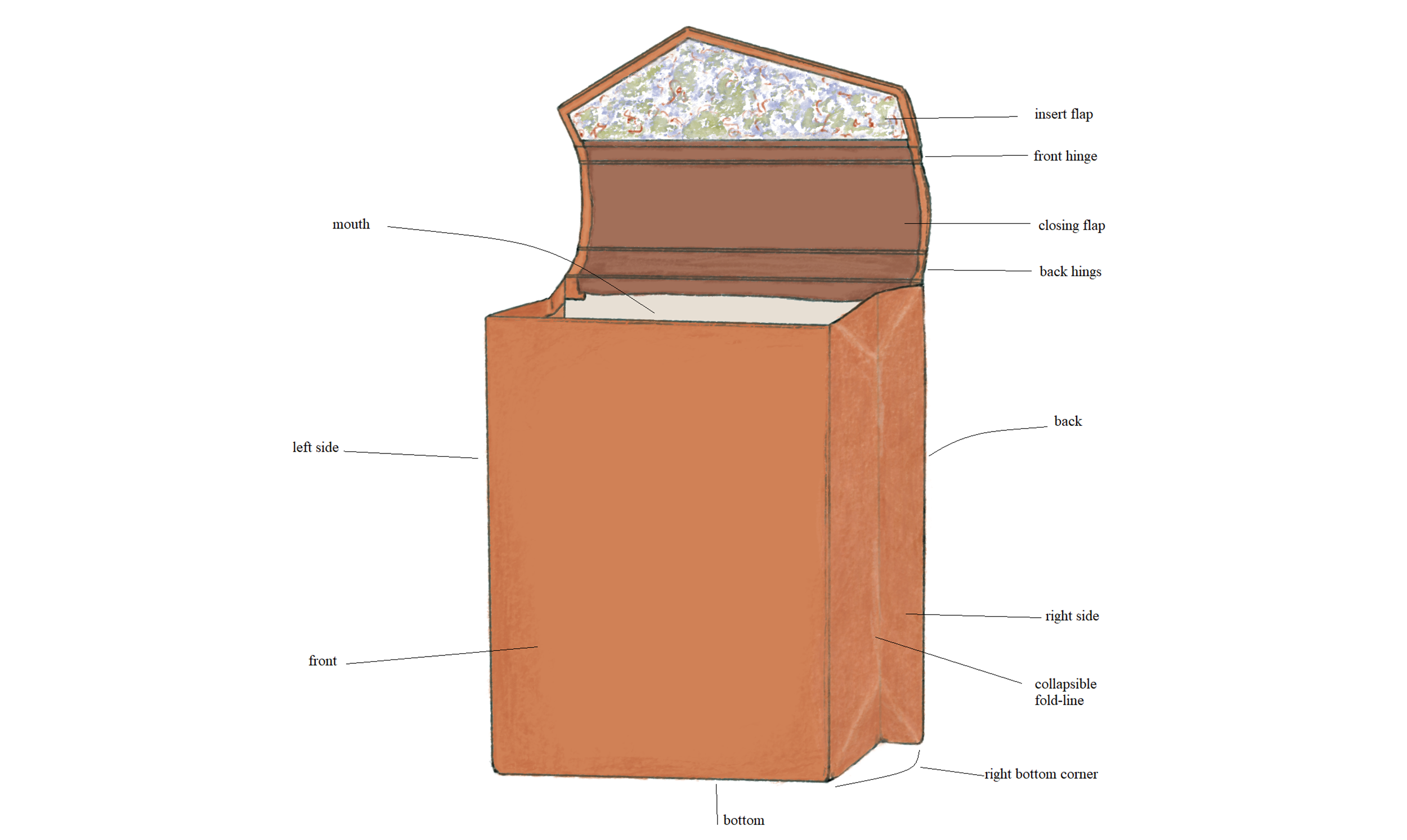

The preliminary study in the Leiden collection eventually led to a wider study, and a first publication on the topic, including a terminology for describing the composite parts of slipcases (available below).

______

Further reading

David Plummer, Paul Hepworth, and Karin Scheper, 'Between Bag and Box: Characteristics and Conservation Issues of the Islamic Slipcase'. In: Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding Vol. 8, ed. Julia Miller, 2023, Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Legacy Press, pp. 458-509.

Karin Scheper, 'Bindings, Bags and Boxes: Sewn and Unsewn Manuscript Formats in the Islamic World'. In: Tied and Bound: A Comparative View on Manuscript Binding. Studies in Manuscript Cultures. Allesandro Bausi and Michael Friedrich (ed.). Berlin: De Gruyter, 2023, pp. 121-154. Open Access: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783111292069-005/html