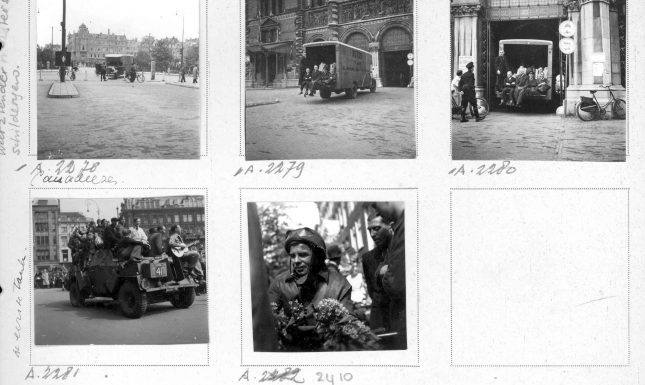

Emmy Andriesse: forbidden photographs of the hunger winter and liberation of Holland, 1944-1945

Emmy Andriesse photographed the last years of World War II in Amsterdam while putting herself in serious danger. Her photographs, now in the Leiden Special Collections, gained iconic status in Dutch visual history.

The year 2020 marks the international commemoration of the ending of World War II, 75 years ago, and the liberation of areas in many countries all over the world from aggressive occupation. Leiden University – abiding by the motto ‘praesidium libertatis’– holds a remarkable photography collection, bearing witness to this liberation in The Netherlands. The author of these photographs, a communist, Jewish, female photographer, Emmy Andriesse (1914-1953), lived in Amsterdam during these last years of the war. While putting herself in serious peril only months after Anne Frank was deported to Auschwitz on 4 August 1944, she photographed the last, harsh hunger winter of 1944-1945 in Amsterdam, as well as the thrilling relief and happiness of the liberation from German occupation by the Allied Forces in May 1945. Her pictures still move us today.

Emmy Andriesse enjoyed her education in the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. Since photography, in those days, was not considered an art form yet, Andriesse followed courses in graphic design and visual communication. Her sole focus on photography soon caused the nickname ‘Emmy Leica’ (after the famous camera brand). As a result of her communist social engagement, she moved to Amsterdam: an international melting pot of artistic and political ideals and movements. Artists fleeing from National Socialism had gathered in the Dutch capital before the war because the Netherlands was known for its liberalism and tolerance and had remained neutral in World War I.

Although Emmy Andriesse was a photographer of all kinds of subjects and earned a living as a reportage photographer working as a freelancer for illustrated magazines, her photographs of war and liberation became the most famous in her oeuvre. Some of her photographs of children suffering the hunger winter, like this boy with pan, even gained iconic status in Dutch visual history. While much of the Netherlands was already celebrating freedom, the march of the Allied Forces to the North halted in the Autumn of 1944. The Western part of the Netherlands suffered one last winter in which the German occupation manifested itself harsher than before. As a result of the German rationing of food and goods, especially fuels, together with the extreme cold of that winter, many people died in the occupied territories, especially in larger cities.

Being Jewish and photographing in the streets of Amsterdam were two things that put Andriesse at serious risk of arrest, deportation and death, would she have been discovered and halted by the occupiers. Her urge to visually bare witness to the severe situation and what was happening, made her go anyway. A declaration, released by Amsterdam based anthropologist and doctor Arie de Froe in 1944, affirmed her as being from a branch of the Jewish people tolerated by the Nazis and thereby protected Emmy Andriesse while walking the streets. Photographing, however, was a forbidden practice in itself. The very photographs she made illustrate her determination to photograph despite the dangers.

How big was the relief, on 5 May 1945, when the message of German capitulation reached Amsterdam? Emmy Andriesse photographed the insecure days of fear and waiting before the first Canadian tanks arrived in the capital.

On May 8th, they finally appeared. From the South-East, crossing the Amstel over the Berlage bridge, were many Amsterdam inhabitants were waiting, raging with emotions from the relief

Emmy Andriesse continued her remarkable work after the war, though she would devote herself to more lighthearted subjects. In Paris, she photographed artists like Roberto Giacometti in their studios as well as working models and designers of High Fashion. In the South of France, she followed in the footsteps of Dutch 19th-century painter Vincent van Gogh’s and photographed landscapes and types of people like he had painted before. Sadly, cancer ended the life of the, then still young (39 years old), photographer in 1953. This exact year also marked the foundation of the photo collection at the Print Room, by professor Henri van de Waal (1910-1972), at the Leiden University art historical institute. While until around the 1990s, no Dutch art museum considered photography an art form or heritage at all, Van de Waal in 1962 decided to buy the entire Emmy Andriesse collection, containing negatives, contact albums, notebooks and photographic prints from her widower, Dick Elffers. As a visual resource, the Emmy Andriesse collection represents an artistic current of 20th-century photography and, at the same time, bears witness to a dramatic episode in Dutch history.

See also: The Emmy Andriesse entry in Depth of Field Journal and the Leiden University Libraries collection guide.