Egyptian Screen Goddesses and Western Fashion: Freedom or Oppression?

Popular Egyptian cinema abounds in screen goddesses in high heels and short skirts. Is this the typically Western idea of being free to wear whatever you like? Or of women dressing like tarts in order to attract men?

If you watch Egyptian films from the 1940s to the 1970s you are bound to be overcome by a feeling of nostalgia. They are the products of a dream factory: sweet romantic nothings, in which the (male) hero conquers the prettiest girl after eliminating countless obstacles. They were essentially copies of Hollywood films which were ‘translated’ to adapt to local tastes. And just like Bollywood films, they found their way across the border to an audience of millions. But interestingly, the Egyptian film also adopted an Orientalist element from the Hollywood film: the belly dancer and the ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’. More than 200 films served as a vehicle for a belly dancer who performed under the name Taheya Carioca (1915-1999). Twisting all men around her little finger, she married fourteen times. Other films featured popular singers such as Farid al-Atrash and his beautiful sister Asmahan, or Abdel Halim Hafez aka ‘the Brown Nightingale’. In the cavernous cinemas of Cairo, the sound quality was always so poor that the dialogues were impossible to follow, but that didn’t really matter.

Traditionally, these films staged a completely westernised ‘high society’ of brandy-bibbing gentlemen in tails and ladies with a cleavage against a background of Louis-Seize furniture and chandeliers. There was not a single veil in sight, or it belonged to an old decrepit grandmother. The Arab audience was regaled with a charade of a liberal, cosmopolitan élite rather than their own life or traditions. The average Egyptian cinema-goer had a great time, but never regarded it as a model for their own life. The morality of these films was never completely black-and-white: the public appreciated the character of a belly dancer or prostitute who needed the money for her family, or who was spying against the British.

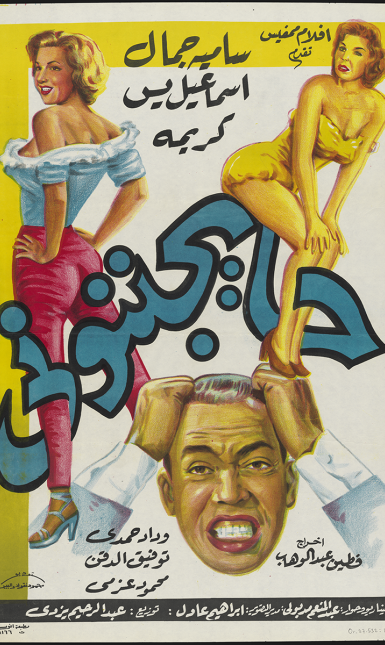

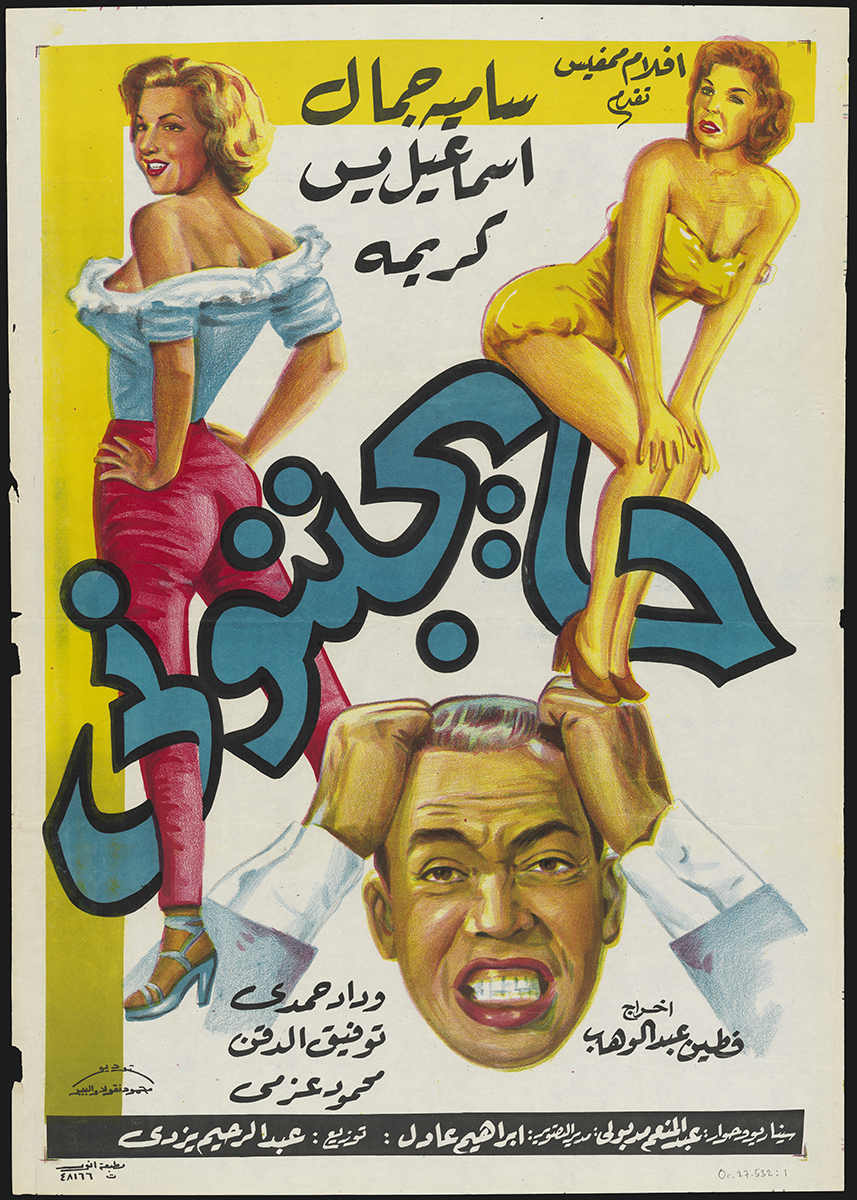

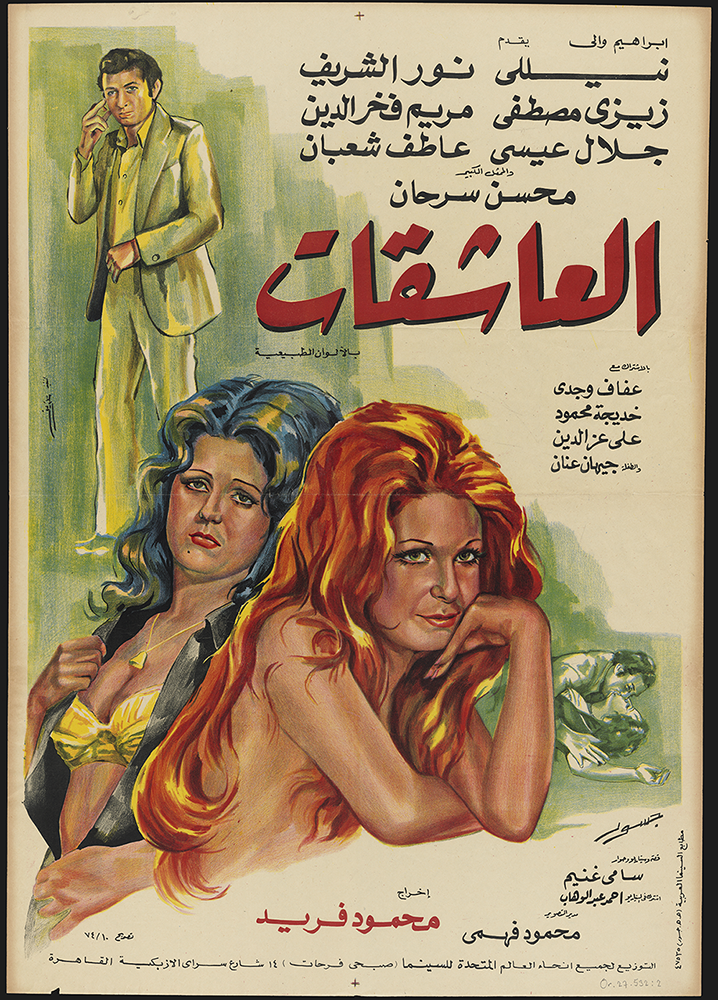

In 2016 Leiden University Libraries acquired a collection of circa 150 Egyptian film posters from 1950-1980, offered by the German-British collector and dealer Thomas Hill, owner of PosterArc. Though modestly sized, the collection offers insight into a bygone era. The lithographed posters often feature scantily dressed women you would never meet in the street. This was, of course, a teaser: the Egyptian film censor saw to it that all kissing was limited in both frequency and duration.

Even though the headscarf, the niqab and the beard have conquered the Middle East by storm ever since the 1980s, it appears that popular Egyptian cinema has retained many of its former characteristics. But the accent has shifted to action movies with fast cars, hand-to-hand combat in the style of Bruce Willis, explosions and the unavoidable type of the Bond girl tottering through the battle scene in her high heels, trying to be saved (by a man). What sort of Weltanschauung are we dealing with here? Is it Western liberal society, or a traditional Western man-woman relationship? In any case, it is a relief to see that in the modern Arab world, too, there are complaints about witless film blondes (or brunettes) who are nothing but a sex object. To many Muslim girls and women, the headscarf and the niqab have become a symbol of control over their own bodies, and consequently of female empowerment. In the Netherlands, where the niqab is officially banned in a public context, many Muslim women challenge the ban with the argument that they should be free to wear whatever they like just like anybody else, but this is not the kind of freedom Dutch society chooses to offer, at least not to everybody.

This blog post is part of the thematic programme ‘Oppression and Freedom’, in which Leiden University Libraries (UBL) explores views on identity, relations and the interaction between individuals and groups in the past. The programme includes several exhibitions, workshops and lectures on the subject of oppression and freedom. In addition, there will be blogs, videos and podcasts relating to items in the Leiden Special Collections. More information is available on the Leiden University website.