Dried Flowers with a Story

The therapeutic powers of all kinds of plants.

For researchers, the most interesting things are sometimes those that do not belong in a book at all according to conservation standards. The topic of my research is the development of academic chemistry in the eighteenth century and its influence on medical and pharmaceutical practice. In this period, there was a lot of interest in, but also much criticism of, drugs made from metals. Some scholars have even argued that the demand for metal-based cures exploded. Yet this is hard to prove, as we have but few records of how often particular pharmaceutical recipes were prescribed and prepared. We therefore have to rely on indirect evidence, such as what medics and apothecaries wrote about their practice, patient diaries, prescription notes and recipe books. The latter are particularly interesting if there are traces of use, such as wear, stains, and marginalia.

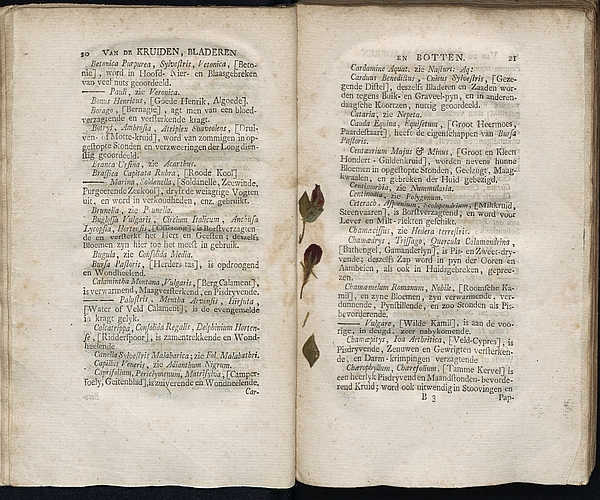

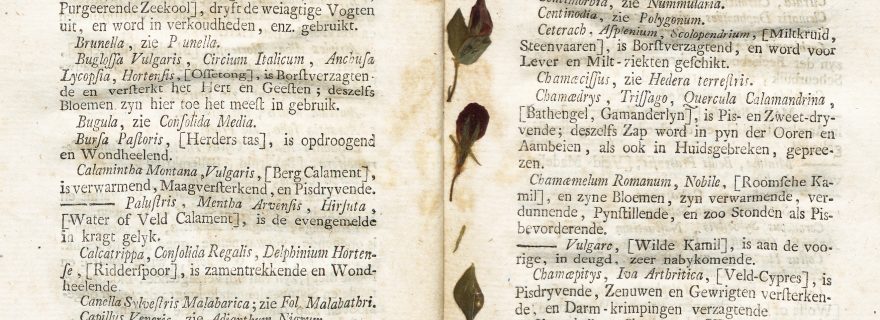

When I recently opened Leiden University's copy of Pieter van der Eyk's Nieuwe Nederduitsche Apotheek (‘New Dutch Apothecary’) from 1753, I found a dried stem with some flowers on it between pages 20 and 21. There is a reason for that stem being kept between those pages: they describe the therapeutic powers of all kinds of plants. Elementary research suggests that the stem is most likely Centaury – called 'hundred-' or 'thousand guilder herb' in Dutch. Indeed, on page 21 we find a description of 'Hondert-Guldenkruid':

'... used, with its flowers, for retained menstrual flow, jaundice, stomach aches, and afflictions of the skin.'

Of course it remains a mystery exactly why the user of this book decided to keep a stem of one of the described plants between the pages of this book, but it does make clear that the book was probably used as a reference work in an apothecary shop – and that herbal remedies were far from obsolete in 1753.

Post by Marieke Hendriksen, postdoctoral researcher in the 'Vital Matters' project, ICOG, University of Groningen