Donation of letters describing an 18th-century voyage between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies

The letters, authored by German Johann Anton Neubronner (1763-1815) on his voyage to the Dutch East Indies are a perfect supplement to three major collections gathered by Neubronner’s famous grandson: Indologist Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk.

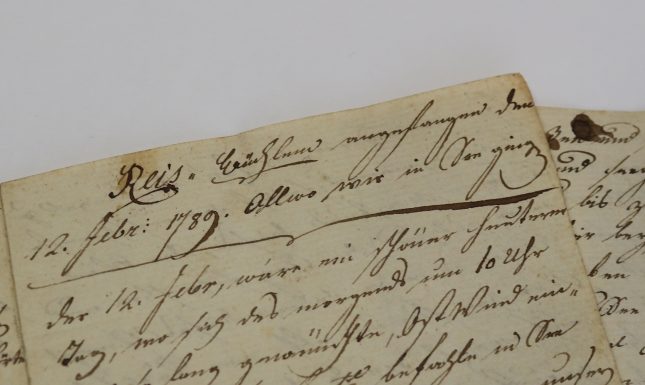

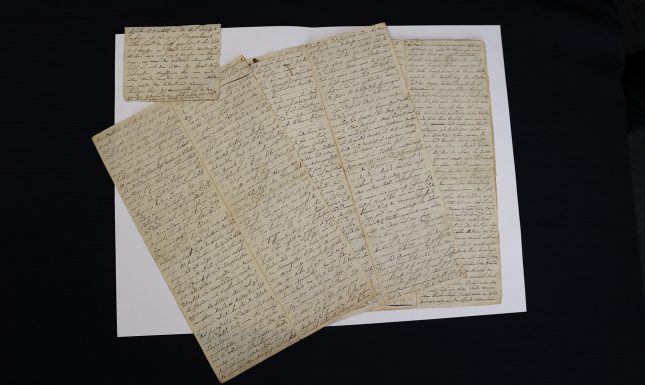

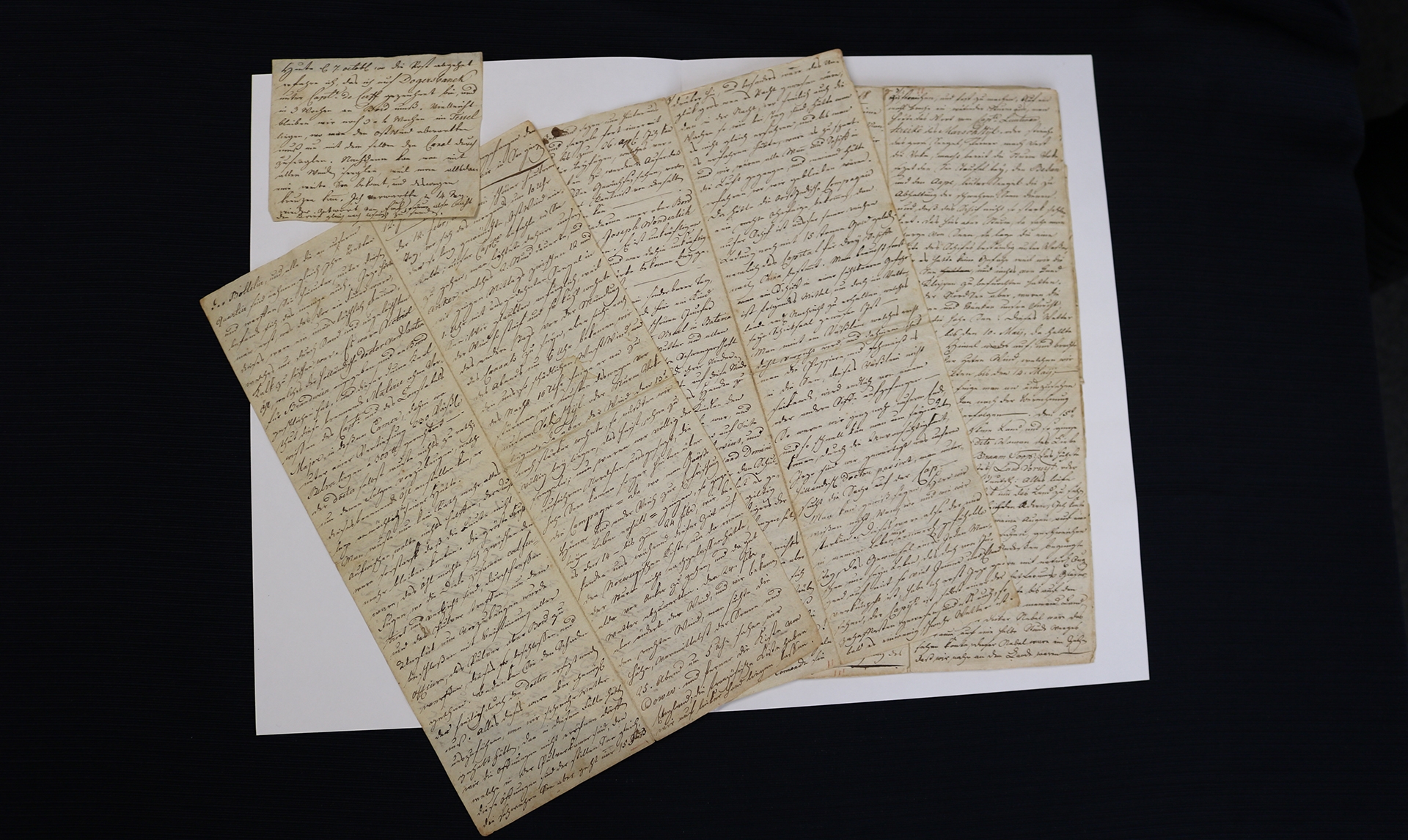

Eye-witness reports that depict the everyday challenges of an 18th-century ship voyage from the Netherlands to the Dutch East Indies are very rare. On 3 August 2020, seven comprehensive letters, one in fact in the style of a journal, were donated to the Leiden University Libraries’ Special Collections. The letters were authored by the German Johann Anton Neubronner (1763-1815), who sent them from Amsterdam, the Cape of Good Hope, and Malacca in 1788, 1789, and 1791 respectively. They miraculously survived and now offer the present-day reader a vivid impression of the journey of an early passenger on his way to the East Indies – a dangerous journey that took the better part of a year. The Leiden University Libraries are grateful for the donation of these historical documents, which perfectly supplement three major collections gathered by J.A. Neubronner’s famous grandson, Indologist Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk. The donation also contains two letters by the latter.

In order to help his family financially, Johann Anton took up a five-year appointment with the Dutch East India Company in 1788 - a long way from home. He left his German home in Usingen, a small village just north of Frankfurt am Main, in the late summer for Amsterdam, to sail to Batavia in early November. The freezing cold of a harsh winter, however, delayed the departure of the Doggersbank, but finally, on 12 January 1789, the ship could set sail for Batavia. On his way to the Indies, he was confronted with several life-threatening situations. For instance, when a bottle of acid – clandestinely smuggled on board by the Dutch ship doctor - broke and was about to cause a fire. Extinguishing the fire with water was not an option, and, even scarier, 230 barrels of gunpowder were kept in the storage room right above. To save the ship, the captain decided to throw the barrels of gunpowder overboard. Neubronner dryly states that the doctor will have to refund that loss. He also wonders what could have happened had it been night-time instead:

Neubronner writes at some length about fish that he watches in the ocean:

In all detail he writes about the food on board:

The death of two sailors, one fell to his death, the other died of exhaustion, he mentions only briefly, whereas another event gets more attention:

After surviving storms and treacherous cliffs, the Doggersbank finally reached the Indies safely just before Christmas. After a short stay in hospital – like most of his travel companions he was weakened by the journey - Neubronner stayed with the Head of the slaves’ quarter, also a German. It was that man who advised him to pay a visit to the Governor, Abraham Couperus. So he did, and shortly after he took up his work as an assistant bookkeeper at the ‘Rathe van Politie’. He worked his way up and married into the most influential family in Malacca. Keeping in contact with his own family and friends in Germany, however, proved to be difficult, as contact depended on the few ships that travelled back and forth. Mail would not only take months to reach its destination, but it would take the same amount of time to receive a response.

With Johann Anton Neubronner, a new family dynasty in the Indies had found its beginning. Of the letters that he sent from Malacca, four have survived. They describe his life there, his view on the colonial society and indigenous people, and, subtly, his longing to return to Europe - he never did.

We wish to thank the Neubronner family for this exquisite gift and Witske van der Wielen for being a committed mediator in the donation process. The donation has been registered under the Or.number 27.941 in the Leiden Special Collections and will shortly be available for research in the Special Collections reading room. The letters are written in German and Sütterlin script, a transliteration is available upon request.