Chemicals, Glass and Persistence: Alexine Tinne’s 1862 photography in the heart of Africa

Alexine Tinne mastered mobile photography while the art was still in its infancy, enabling her to create some truly unique photos in mid-19th-century Africa.

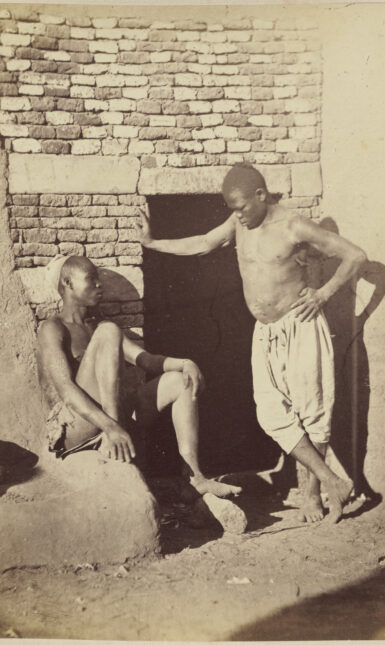

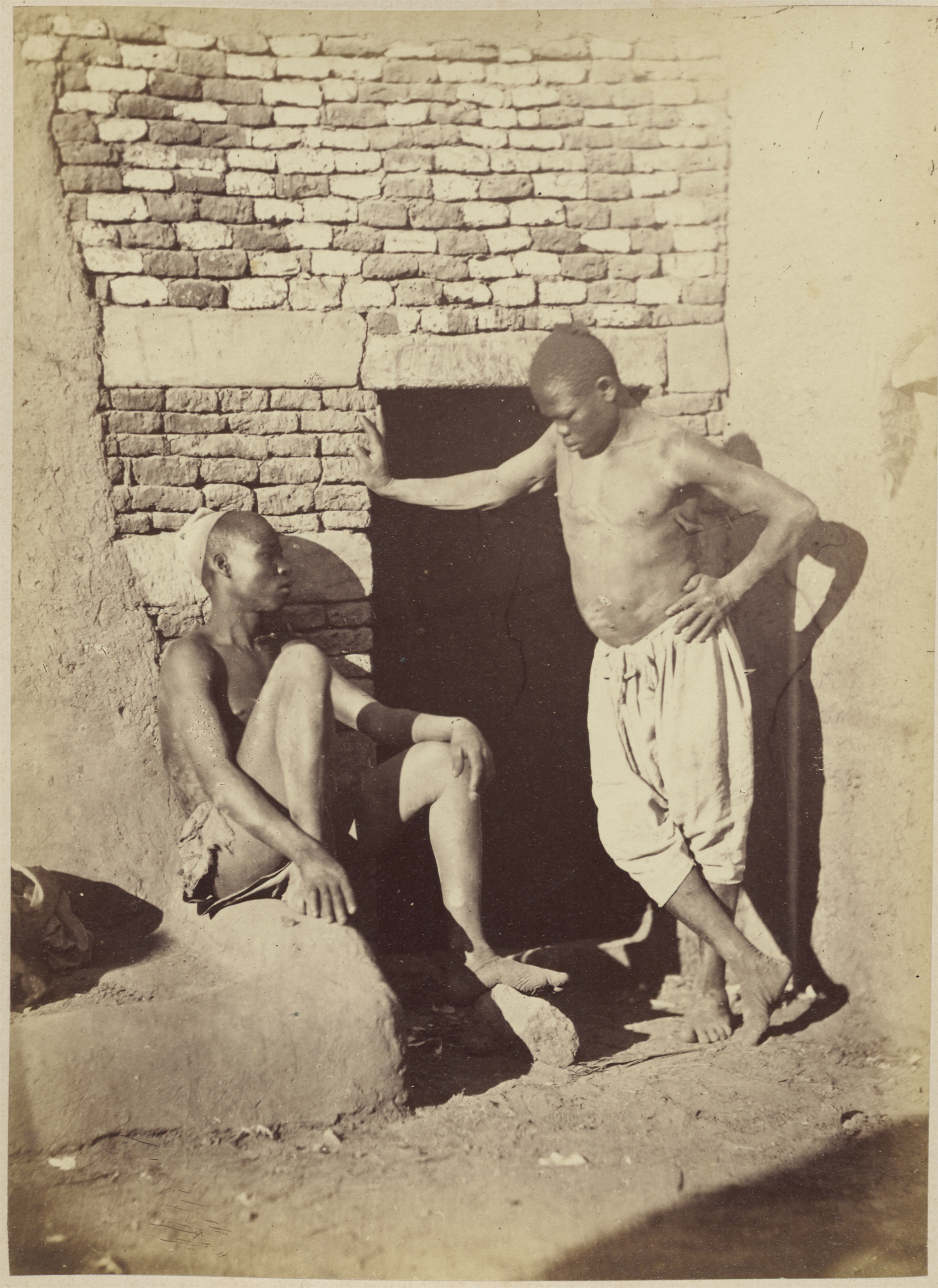

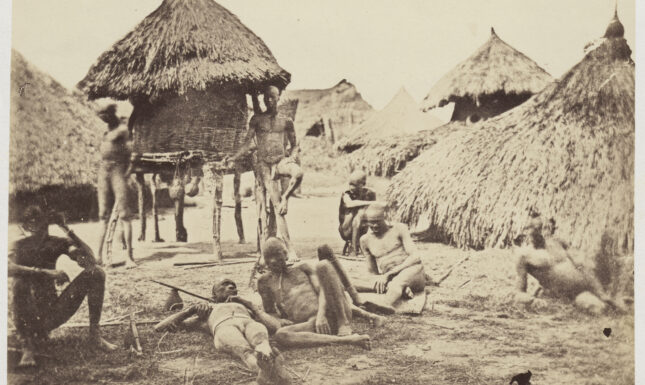

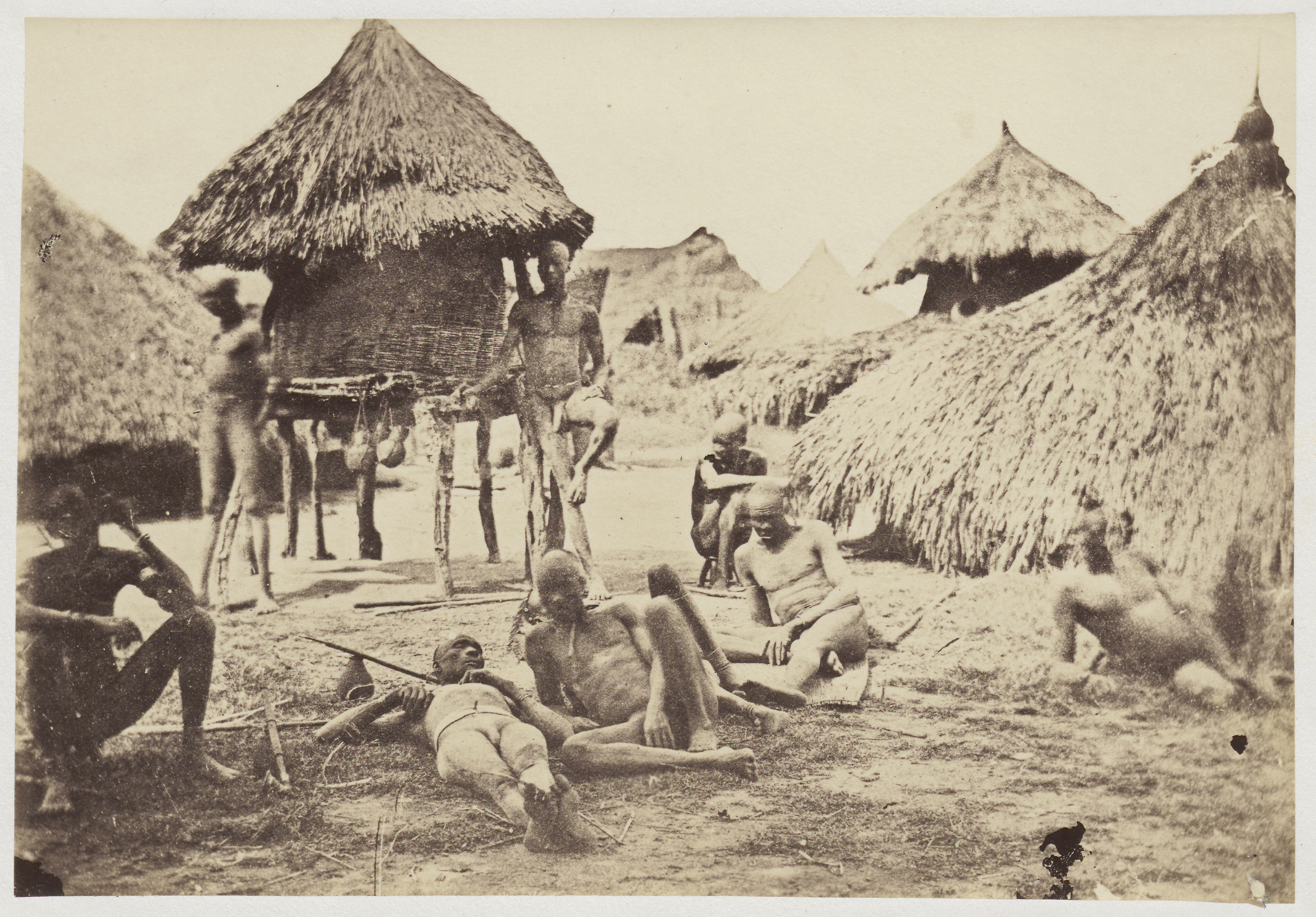

In times of smartphones and instantly ready digital photography, it is hard to understand how difficult it was to take a photograph in the 1860s. Cameras were heavy wooden boxes which had to be put completely still on large wooden tripods. Light sensitivity of the negatives could only be achieved by pouring chemicals on glass plates. After exposure in the camera, they had to be processed on the spot, in a dark, cool and dry place. Consequently, early photographers had to carry or drive mobile dark rooms around when on the move. 19th-century photographers are known to have used chariots, boats or even grave tombs, to be able to work in darkness in these hot African environments. Alexine Tinne probably used a brick building of the Austrian Catholic Mission in Gondokoro, in current South Sudan, when developing the glass plate negatives that lay at the foundation of these photographs, recently acquired by Leiden University Libraries.

While letters and travel reports indicated that Alexine Tinne's expedition had taken her to Gondokoro, the place where the Nile ceased to be navigable, her photographs in the village remained unknown until a few years ago. We have French photo collector and expert Serge Kakou to thank for the incredible work leading to this discovery. Kakou came across the historic photographs while researching the first photographers on the African continent, but was unable to identify the creator of these early photographs of the heart of Africa. It took an exhibition in 2010 in the Haags Historisch Museum and the accompanying 2011 publication about Alexine Tinne by Leiden University researcher Joost Willink, to set him on her trail. After extensive research in literature, archives and travel reports and comparison of the photographs with wood engravings made from the prints for printed publications, Kakou provided extensive evidence for Tinne’s authorship of the unique photographs.

So how did the photographs end up in Serge Kakou’s hands without attribution? The most plausible reconstruction of the story is, that Tinne took the glass negatives she made in and near Gondokoro with her in a wooden box, along with other luggage. After the tragic second Tinne expedition to the Bahr al Ghazal (‘river of gazelles’, a tributary of the Nile), where Alexine lost her mother and was orphaned, she decided not to return to Europe. Instead, she remained living in Africa and travelled north on the Nile. In the years following, she set off on an odyssey on the Mediterranean and had an eventful residence in Algiers; but not before leaving various belongings in her house in Cairo and one or several boxes with glass negatives with a professional photographer in Alexandria. She may have reasoned that a photographer, someone who understood the character and value of photographic negatives, was the best guardian of these precious and vulnerable glass plates.

In the nineteenth century copyright on photographs did not exist yet. Following common practice, the photographer printed and sold photographs from the negatives without mentioning the name of the original photographer. After Alexine’s cruel death in 1869, her family members travelled to Northern Africa to collect her belongings and sell her houses, but the boxes of negatives were probably overlooked. Thanks to the extensive research by Serge Kakou, convincingly presented to Dutch photo experts in a symposium of the Dutch Photographic Society, the story of the photographs was reconstructed. The photographs were convincingly attributed to Alexine Tinne. Now, the way is paved for the photographs to serve as a visual source for research into the identities, lives and history of these African people portrayed.

The unique series of eighteen African photographs could be acquired for the UBL photography collections, with support from Vereniging Rembrandt's Thematic Fund for Photography and Video, the VriendenLoterij Acquisition Fund, Mondriaan Fonds, Hendrik Muller Fonds, and the Friends of UB Leiden. Learn more about the acquisition.