Calendars from the South- and Southeast Asian collections

The concept of time determines human life in the most crucial ways. It is beyond human control, but there has always been the desire to at least manage time by applying structure, measurement, and rules. One of the most decisive and varied means of structuring and measuring time is the calendar.

Calendars come in all sorts and forms. Hardly anyone can do without one. Being an object of frequent use, calendars are often embellished and made visually more appealing, entertaining, or divine, dependent on their function. Religious calendars fulfill an entirely different role than, for instance, the agricultural calendar of a farmer. Generally, calendars are based on a lunar, a solar, or a lunisolar system of time measurement, with innumerous variants from cultures and traditions all over the world. In this blog post, however, I would like to draw attention to another aspect of calendars, one rarely discussed: their materiality.

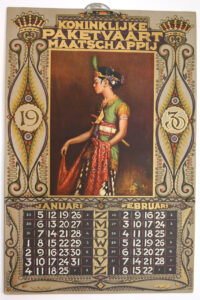

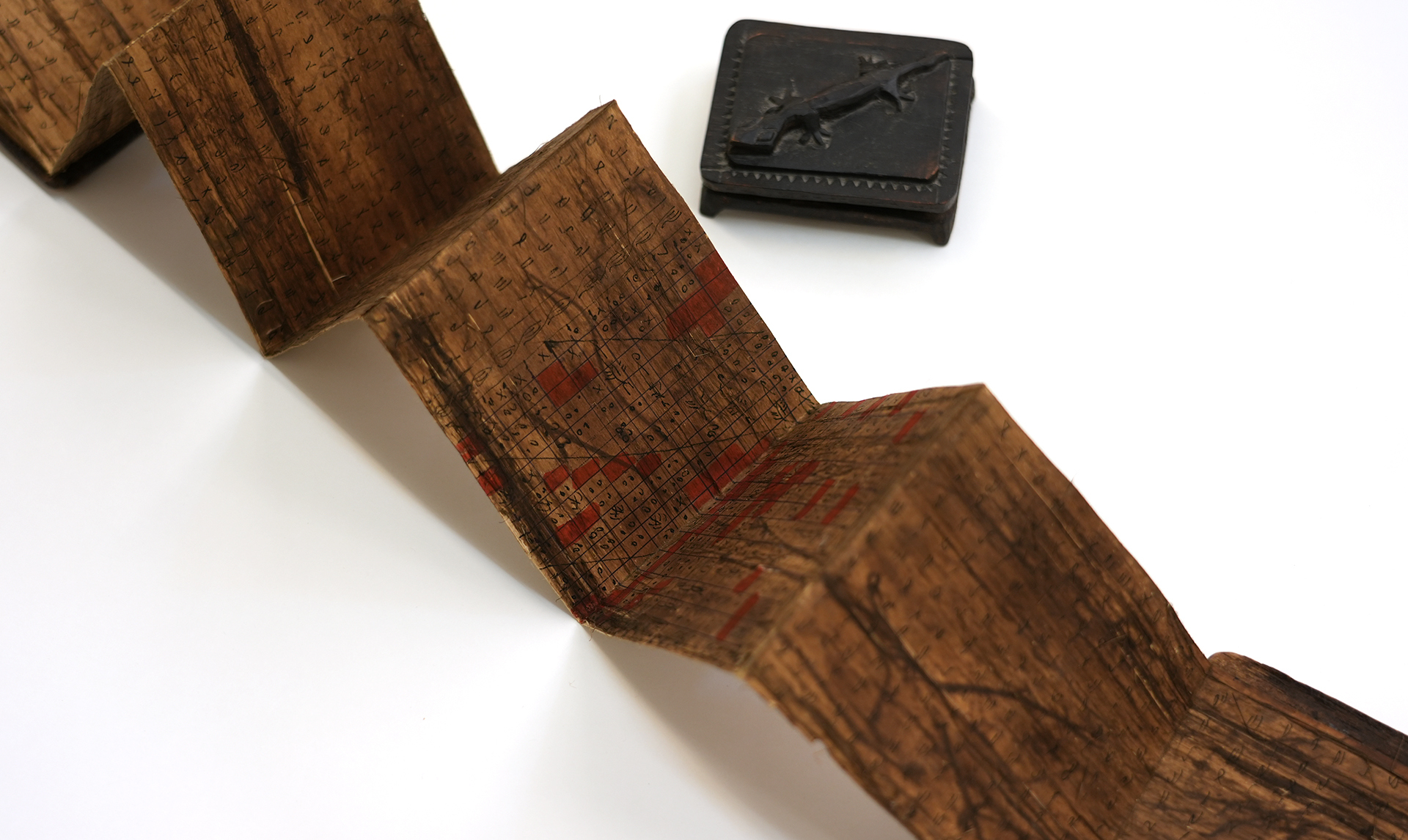

In the Western context, paper has been the most frequently used material since the printing press's invention. Wanted collectable items are those calendars illustrated by famous artists such as J. Portenaar, J. Gabriëlse, or W.G. Hofker (UBL Or. 27.660, Or. 27.652 and Or. 27.653, and Or. 27.193 respectively). The various Batak ethnic groups of Sumatra use different kinds of materials for their manuscripts. Calendars from those traditions are often made of tree bark or bone. The Leiden University Libraries collection houses the famous Van der Tuuk collection of Batak manuscripts (pustaha); many among those more than 300 leporello folded pustaha contain a calendar (for instance Or.28.311; Or. 28.314). Some have beautifully decorated wooden covers (Or. 27.000). Apart from tree bark, bone and bamboo are also used (Or. 27.000; Or. 27.009; Or. 27.625; Or. 28.314).

The pawukon or palintangan is an astrological calendar, often called kamasan, after the region in Bali where it is most famously made. This 210-day calendar originates from the Hindu religion in Bali. Those drawings on cloth often show scenes from myths or from the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. The format differs, but often they are quite large to be hung up during ceremonies and rituals. This astrological calendar is used to determine the likely character of a person, the best day for an activity or festivity, it can tell the user what offerings to make, and it links the human world with that of the gods and myths.

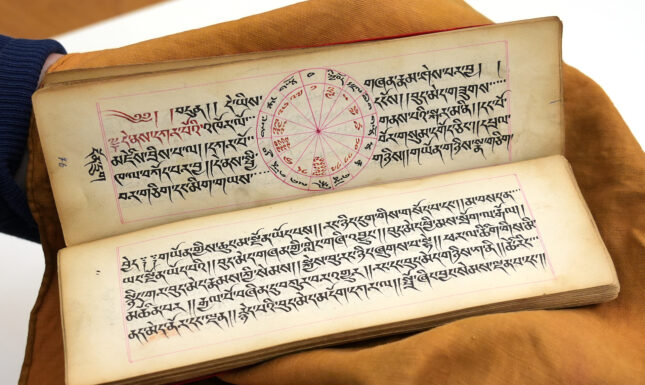

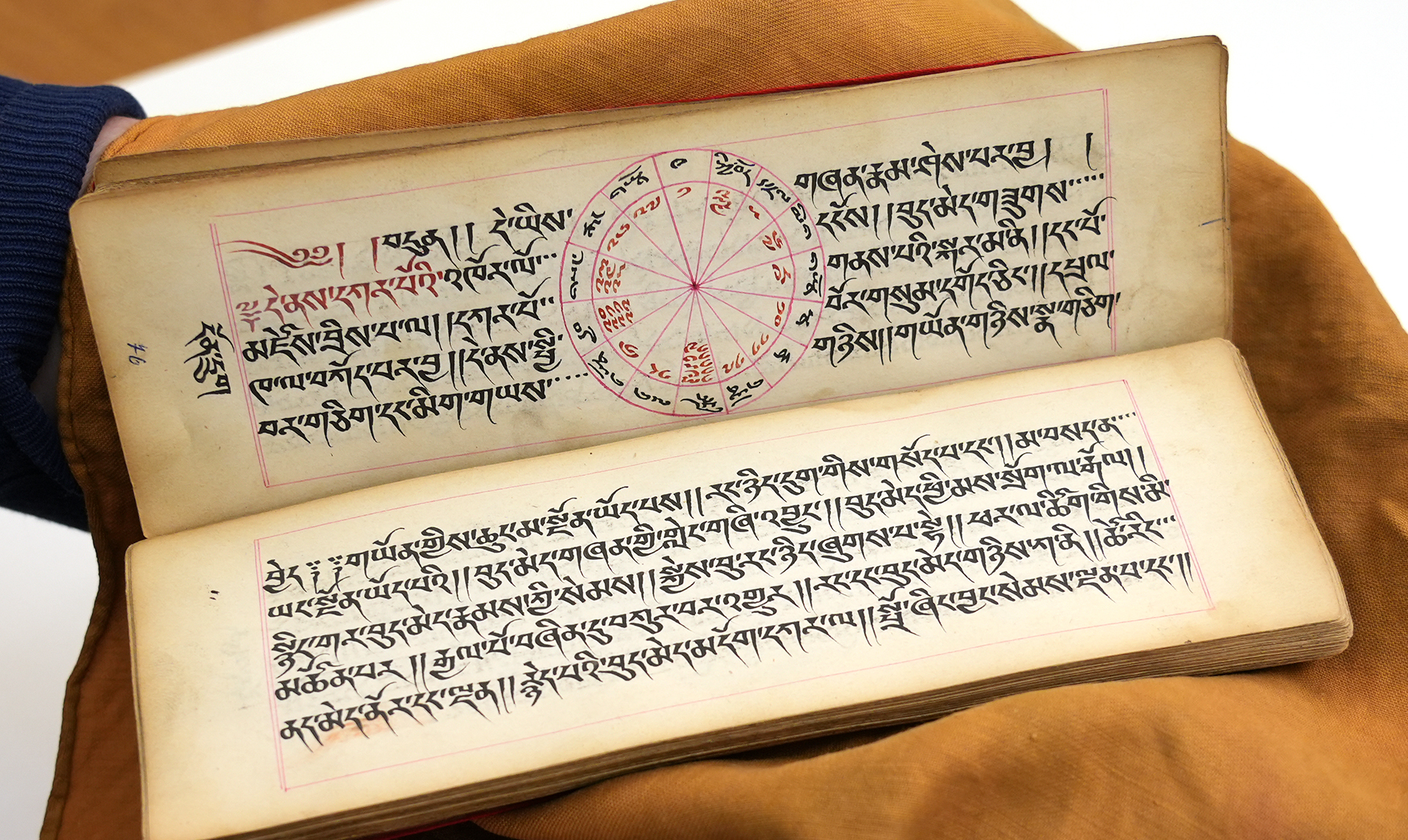

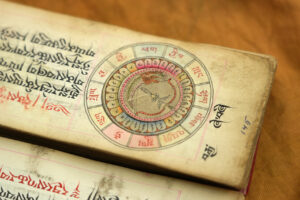

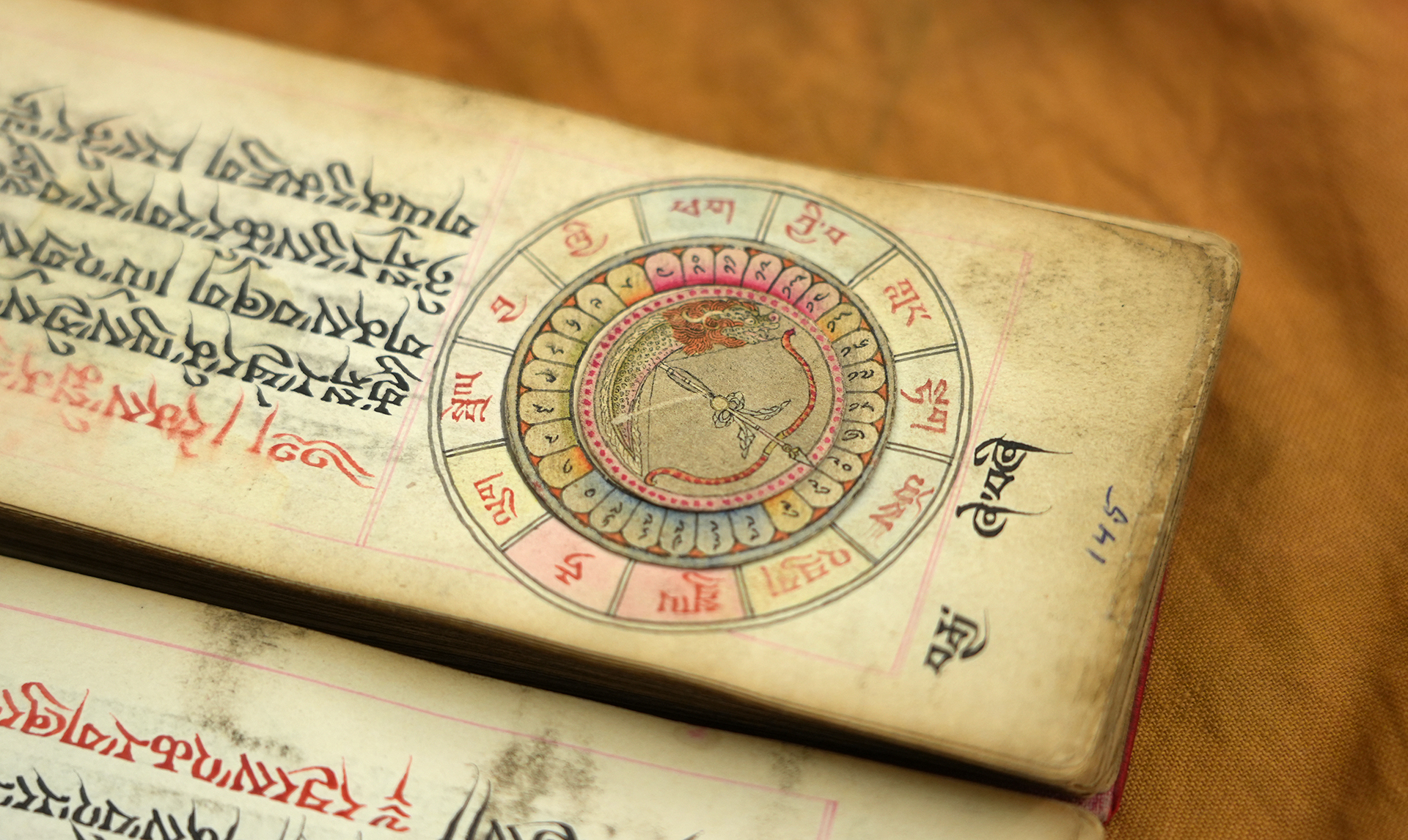

Apart from the calendars from Indonesia described above, the UBL recently also acquired several calendars from India, Tibet and Nepal, with one originating from Mongolia (in Tibetan script). The latter probably dates from the 1950s and contains 205 folios and numerous colourful astrological drawings. But most striking is the chart wheel, which has the ability to spin on one of its folios (Or. 27.144 = Skr 311). This calendar was never meant to be hung on the wall: it came with a fine leather cloth, string attached to wrap it up carefully. Different is the case with the copper Nepalese wall calendar (Or. 28.318): This most recent supplement to the calendar collection is meant to be hung on the wall, it is a protection charm. The graphics on this calendar are based on the traditional astrological mandala Srid-pa-ho: a lotus circle with twelve animals of the Chinese Zodiac system.

It is very likely that there are many more undiscovered calendars In the rich Leiden manuscript collection that make part of a manuscript -- on paper, palm leaf, tree bark, or whatever material. A systematic search for and the research of them would fill a gap in the knowledge we have about calendars and their use in the cultures discussed above.

Leiden University Libraries holds hundreds of these kinds of calendars in its collections. Learn more about doing research in our Special Collections.

Further reading

- Frederik Schreuder, Een wereld vol almanakken: 100 bijzondere exemplaren, (Zutphen 2023).