An intimate conversation between present and past in Loes Huis in ’t Veld’s "Cavafy my father and me"

Leiden University Libraries recently acquired a beautiful work of art in the form of a book: "Cavafy my father and me" by Loes Huis in 't Veld. Cavafy expert Maria Boletsi discusses how this artistic rendering fits into the broader tradition of adaptations of Cavafy's works.

Constantine P. Cavafy (1863–1933) was a Greek diasporic poet who lived most of his life in Alexandria, Egypt, writing verses in Greek and, only occasionally, in English. A child of a well-off Constantinopolitan family in Alexandria, in his early youth he saw their family fortune dissipate following his father’s premature death and he ended up working for thirty years as a clerk at the Irrigation Office in Alexandria under the British. As a member of the Greek diaspora of Alexandria, Cavafy found himself in the periphery of the British Empire and of Greece. His liminal position in between worlds was enhanced by his homosexuality, which is latently present in his early poetry but became more daringly manifest in later verses. Although Cavafy only set foot in mainland Greece a couple of times in his lifetime, in his poetry he was deeply concerned with the history of the Hellenic world. The idiosyncratic vision of Hellenism he developed, however, moved away from the glories of classical Greece: Cavafy was fascinated by periods of decline as well as historical contexts marked by intense hybridization, cultural syncretism, and encounters between heterogeneous worlds inhabited by people of mixed religions, races, cultural affiliations, and sexual orientations – particularly the Hellenistic period (323 – 32 BCE) and, to a lesser extent, the Byzantine era. Cavafy’s poetic language was hybrid too: a mixture of linguistic registers that included demotic and archaic Greek marked his unembellished, prosaic poetic diction, through which his unique sense of irony took shape.

His idiosyncratic language as well as the themes, historical periods, and deviant characters that took center stage in his poems confused his contemporaries, and particularly Greek literary circles, which saw Cavafy as a misfit in (national) Greek poetry at the time. During his lifetime he had already gained admirers in the English-speaking world, but he ignored offers to publish his poetry in English, most notably by E.M. Forster, a great admirer of Cavafy’s work, and by Hogarth Press, run by Virginia and Leonard Woolf. Cavafy never pursued a proper publication of his poems but opted for a mode of private circulation through self-made collections he gave to people he knew and respected. His fame started taking off towards the end of his life but it was after his death that his poetry came to be widely appreciated in Greece and globally. In the Netherlands, he was introduced to the Dutch letters by Gerard Henrik Blanken, the first professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek studies at the University of Amsterdam (1954-1972), whose self-funded publication of twenty-five translated poems by Cavafy in 1934, Vijfentwintig Verzen, is seen as the first published collection of Cavafy’s poems internationally (Blanken’s Cavafy archive is kept in the special collections of the University of Amsterdam). Cavafy is now recognized as the most important modern Greek poet and a central figure in literary modernism and in world literature. This is perhaps why Cavafy, in a prescient self-assessment he wrote in 1930, referred to himself as “an ultra-modern poet, a poet of the future generations” (trans. Peter Jeffreys).

Indeed, Cavafy’s resonance today is far-reaching. His verses speak to future communities of readers and to existential, cultural, sociopolitical, and theoretical concerns and desires that mark the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries – including questions around the relation of self and other, coloniality and postcoloniality, modernity, multiculturalism, diasporic and queer identities. The countless ways in which his poetry has been interpreted, translated, cited, used, adapted, and restaged by writers and artists in diverse media – including literature, visual and performance arts, and music – testify to his worldwide appeal. One of the latest manifestations of his poetry’s resonance in contemporary artistic imagination is the festival “Archive of Desire” organized in 2023 by the Onassis Foundation (owner of the poet’s archive) in New York on the 160th anniversary of Cavafy’s birth: a week-long interdisciplinary festival exploring the global resonance of Cavafy’s poetry through performances, digital art presentations, film screenings, poetry readings, literary discussions, and other live events.

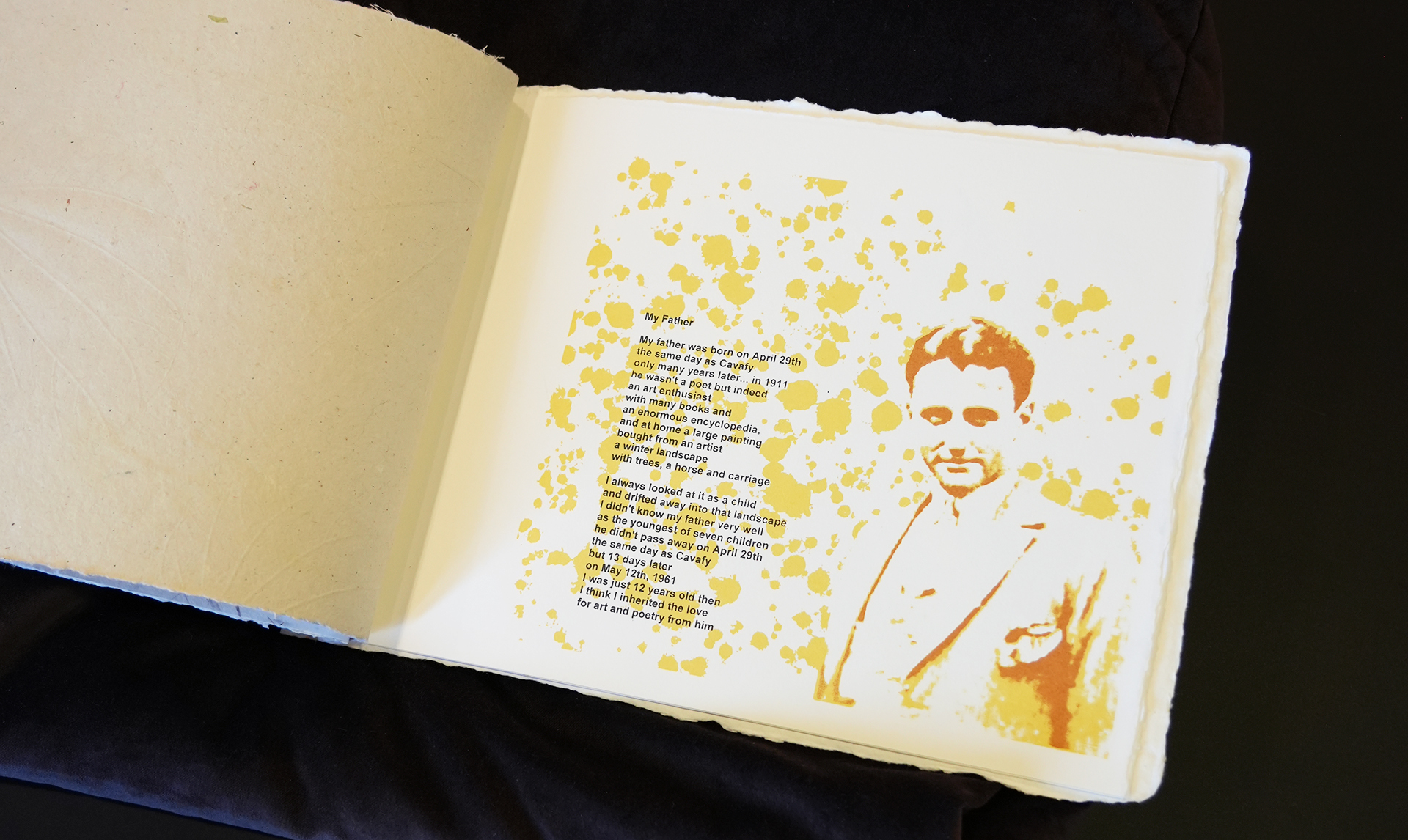

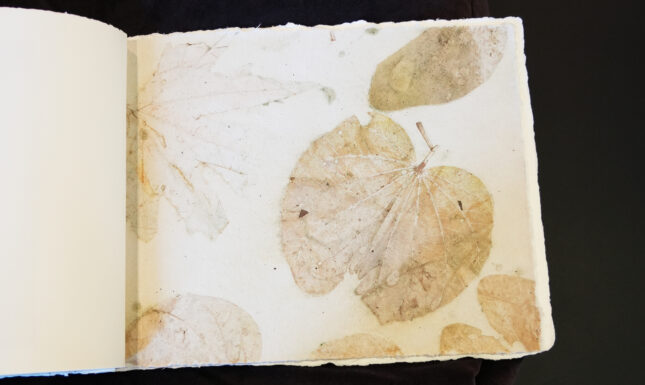

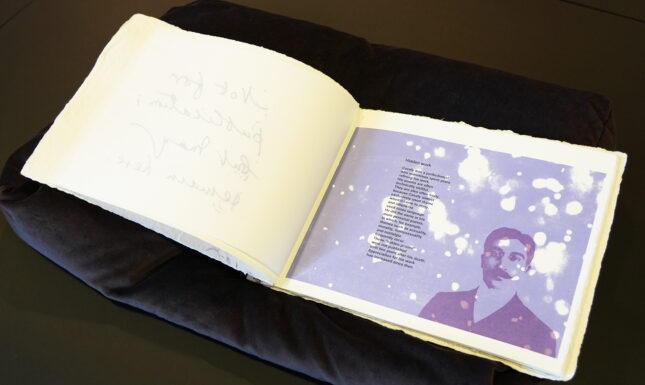

Loes Huis in ’t Veld’s book C.P. Cavafy my father and me (Κ. Π. Καβάφης o πατέρας μου και εγώ) recently joined the array of artworks that respond to, and engage with, Cavafy. This artistic edition stands out for the intimate, personal manner in which it involves Cavafy in the artist’s relation with her father. With each page, in ’t Veld gives us bits and pieces of the puzzle of a ‘conversation’ between Cavafy, her father, and herself – a puzzle that remains incomplete, or, better said, ongoing. The book brings together verses by Cavafy, some information about Cavafy’s life, portraits of the poet that are artistically recreated or reframed by the artist, images of herself and her father, bits of information about her father’s life and their relationship, and a poem by the artist herself that broaches the process of artistic creation: all visually framed through Loes Huis in ’t Veld’s elegant artistic vision. The pieces of this conversation are not causally connected in a coherent narrative, but unfold in a metonymical relation to each other: each partner in this triangulated conversation ‘touches’ the other through associations, serendipitous coincidences, and seemingly random facts – such as the birthdate Cavafy and the artist’s father shared, April 29, or the fact that both Cavafy and in ‘t Veld lost their father at an early age.

Why does Cavafy come between her and her deceased father, as a “third wheel,” so to speak, in an intimate conversation? Although the artist provides no explanation, perhaps we can begin to find an answer in Cavafy’s poetry: a poetry obsessed with the past, loss, death, and memory, yet also turned towards the future and addressing future generations. Cavafy’s poetry, as I argue in my recent book Specters of Cavafy, can be seen as a poetry of conjuration. Instead of a means of recording memories, past events, and characters, poetic language for him was a form of poiesis that does not “represent” but “presents” in the sense of “making present”. Many of his poems try to momentarily summon specters – past lovers, dead loved ones, fictional or historical characters – onto the poetic stage. These poetic conjurations do not always succeed – in many poems, the speaker’s memory fails him – and when they do succeed, the spectral figures that appear from the past are always fleeting, never permanent.

Perhaps, consciously or not, Loes Huis in ’t Veld found in Cavafy’s verses a model for summoning the departed in the present – in this case, her father – and temporarily defying death’s finality. The artist, we read in one of the booklet’s pages, did not get to know her father well because he passed away when she was young and she was the youngest of seven siblings (just as Cavafy was the youngest of seven brothers). Nevertheless, she inherited her love of poetry and art from him, as she tells us; Cavafy becomes part of that inheritance. Cavafy’s life was also marked by death and loss early on: besides his father, who died in 1970, only between 1896 and 1902 he lost three of his brothers, his mother, an uncle, his maternal grandfather, and two close friends. He lived his life and wrote his poetry in the company of ghosts and in search of poetic strategies for keeping death and finality at bay.

Loes Huis in ’t Veld’s book tries to call upon Cavafy and her father through each other. We can better understand her venture by juxtaposing it with Cavafy’s “In the month of Athyr” (1917): in this poem, the poetic subject acts as a reader-archeologist, trying to decipher the writing on a fragmented, half-destroyed tombstone of a young dead man, Lefkios (for the Greek original see here and for an English translation by E. Keeley and Ph. Sherrard see here). The poem stages an attempt to make Lefkios come to life, momentarily, through poetry, but the impossibility to fully decipher the tombstone’s inscription and to ‘reanimate’ the dead man also projects the past’s irreversible loss. In the end, the poem’s speaker realizes that Lefkios “must have been greatly loved”: a love that can, at times, forge connections across temporal frames and momentarily conjure the dead. In Loes Huis in ’t Veld’s engagement with Cavafy and her father, love also creates a similar cross-temporal connection.

In ’t Veld’s edition includes only two poems: the poem “Hidden Things” (“Κρυμμένα’”) by Cavafy and an untitled poem by the artist herself, in which she casts her poetic creation as a process whereby the “pencil or chalk” creates shapes “despite the resistance of the paper of the emotion that guides them.” Her poem ends with the phrase “work in progress,” which almost reads as an invitation for readers/viewers to see the booklet too as part of an unfinished, ongoing project. Cavafy also hated endings and conclusions. The large body of unfinished poems he left behind, comprising several drafts of poems, testifies to his desire to keep endings (and by extension, death) in abeyance; “I do not strongly believe in the absolute value of a conclusion,” he wrote in an early essay on Shakespeare in 1891 (trans. Peter Jeffreys).

It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that in ‘t Veld’s edition only hosts a poem that Cavafy decided not to publish or circulate during his lifetime. In one of the booklet’s pages we read, in Cavafy’s handwriting, the phrase “not for publication; but may remain here.” Cavafy used this phrase for writings that were not destined for the public eye. He could not face the ‘risk’ of publication of some of these poems – a very real risk for a homosexual poet at the time – but wanted to keep them in his archive, waiting, perhaps, for future communities of readers who would include people “made just like me,” as he wrote in “Hidden Things.” He was hoping for a community of readers, including queer readers, that was yet to come and that has by now, in the 21st century, embraced him and given him a prominent place in world literature.

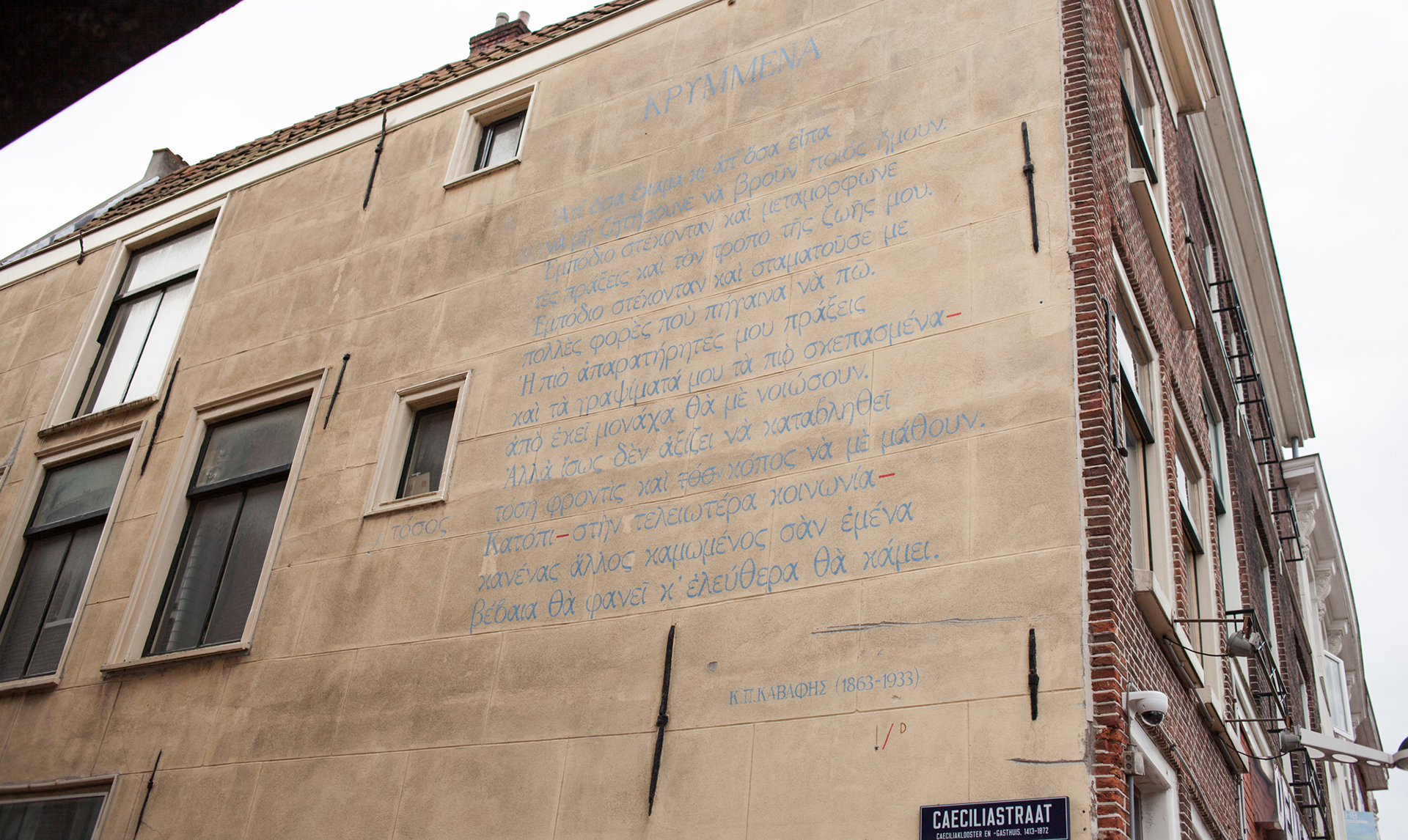

In ‘t Veld informs readers that Cavafy’s “Hidden Things” can be found written on a wall in Leiden as one of Leiden’s so-called “wall poems” (muurgedichten) – not hidden, but exposed in public space: another metonymical trace that links Cavafy with a town he never visited and acts as proof that his poetry found the future readers he anticipated. The artist’s intimate conversation with the specters of Cavafy and her father testifies to the way Cavafy’s poetry keeps haunting future readers and artists in very personal ways. If Cavafy was, as he called himself, a “poet of future generations,” he does not owe this enduring resonance to a poetry that is ‘universal’ or of ‘eternal’ value. In fact, he did not see his poems as applicable to all readers: “the poems one writes […] are true to other lives […] – not generally of course, but specially – and the reader to whose life the poem fits admires and feels the poem,” he wrote in a text from 1903. His poetry did not contain a ‘one-size-fits all’ truth. In a note from 1905, Cavafy used the metaphor of a suit that only fits a few people: “Like a good tailor who fashions a suit that fits one man (or even two) resplendently; and an overcoat that might suit two or three – thus for me might my poems be made ‘to fit,’ in one case (or perhaps in two or three)” (trans. Peter Jeffreys). Retrospectively, this statement proved to be rather modest considering the many communities of future readers who would find perfect “suits” in his poems. Loes Huis in’t Veld’s artistic rendering of her conversation with Cavafy and her father shows how many forms those “suits” that Cavafy gave us can take in the creative hands of contemporary artists, and how many different lives they can be made to fit, through their continuing ability to facilitate conjurations and open-ended conversations between past, present, and future.

About the author:

Maria Boletsi is Associate Professor in Literary Studies at Leiden University and Endowed Professor of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Amsterdam (Marilena Laskaridis Chair).

Symposium

Leiden University Libraries will organise a symposium on Cavafy and his works on 9 December 2024. More about this symposium will be communicated via the website of Leiden University Libraries in the coming days.

Further reading:

- Loes Huis in 't Veld, Κ. Π. Καβάφης o πατέρας μου και εγώ (Ikarosprint, 2024)

- Maria Boletsi, Specters of Cavafy (University of Michigan Press 2024)