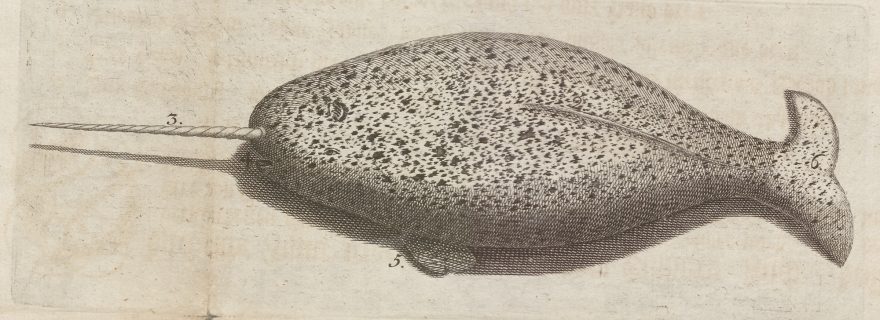

A unicorn fish aground in 1736 in the Elbe estuary

Wasn’t it obvious then, that the ‘horn’ of this sea animal would have the same antidotal qualities as that of its terrestrial counterpart?

It is always a fascinating event when curious fishes or whales, alone or in herds, and dead or alive, are stranded. So the inhabitants of Hamburg seized the opportunity to examine a narwhal, which had been caught in the river Elbe in 1736. Or rather it was a unicorn fish, as they called the beast. An illustration of the animal can be found in the last pamphlet of the German series of the Bibliotheca Thysiana, a broadsheet, measuring 28 x 33 cms. (shelfmark THYSPF DUI 106).

The engraving shows a male unicorn fish, with its characteristic spiral tusk. Above the illustration a text is placed, which reads in translation:

True illustration and description of the unicorn fish, caught in the Elbe river at low tide, and exhibited in February 1736 in Hamburg in a ship at the quay.

In the illustration small numbers are placed at characteristic details, such as the tusk, the small teethless mouth, the pelvic fin, and the tail. The numbers refer to printed annotations, in which some peculiarities of the animal are explained. It concerns the so-called ‘unicorn fish’, a kind of whale, which is mentioned in several itineraries to Greenland. The length of the animal, without the six feet tusk, was eighteen feet (about 5,5 m), its height five ells. The smooth skin, without scales, shows a pattern of black and white spots. A ‘fish’ of this type had never been seen before in Hamburg, for which reason many interested people made drawings of the animal.

As is indicated by the name unicorn fish, the narwhal was an animal with a history. For centuries, all over Europe, a tusk of a narwhal had been fostered as a fabulous treasure, in the unfaltering conviction that it was the horn of a unicorn, an animal which had never been seen by anyone alive. The Danish scholar Ole Worm, professor in Copenhagen, however, had demonstrated already in 1636 that all known unicorn horns originated from narwhals. He also denounced another old fable, i.e. that the horn contained an antidotal power. Two pigeons and two kittens paid with their lives to demonstrate that Worm was right.

It took quite a long time before Worm’s conclusions were generally accepted. Once the presumed unicorn tusks appeared to have come from narwhals, the only palpable proof of the existence of the quadrupled unicorn did fall apart. But this consideration was rather neglected in the learned debate on Worm’s conclusions. On the analogy of the presumed relation between lion and sea lion, dog and seal (= sea dog) etc., people were tempted to consider the narwhal as the maritime counterpart of the quadrupled unicorn, viz. the sea unicorn. Wasn’t it obvious then, that the ‘horn’ of this sea animal would have the same antidotal qualities as that of its terrestrial counterpart? Still in the eighteenth century unicorn powder, named unicornu in the Latin of the apothecaries, had a certain renown as an effective medicine against all kinds of infections and diseases.

Post by Wim Gerritsen, Professor Emeritus of Medieval Dutch Literature at Utrecht University (1968-2000), and Professor Emeritus at the Scaliger Institute of Leiden University (2002-2007).