A Medieval Matthäus-Passion

This is what the ‘score’ of a St Matthew Passion looked like, long before Johann Sebastian Bach was to create his famous Oratorio.

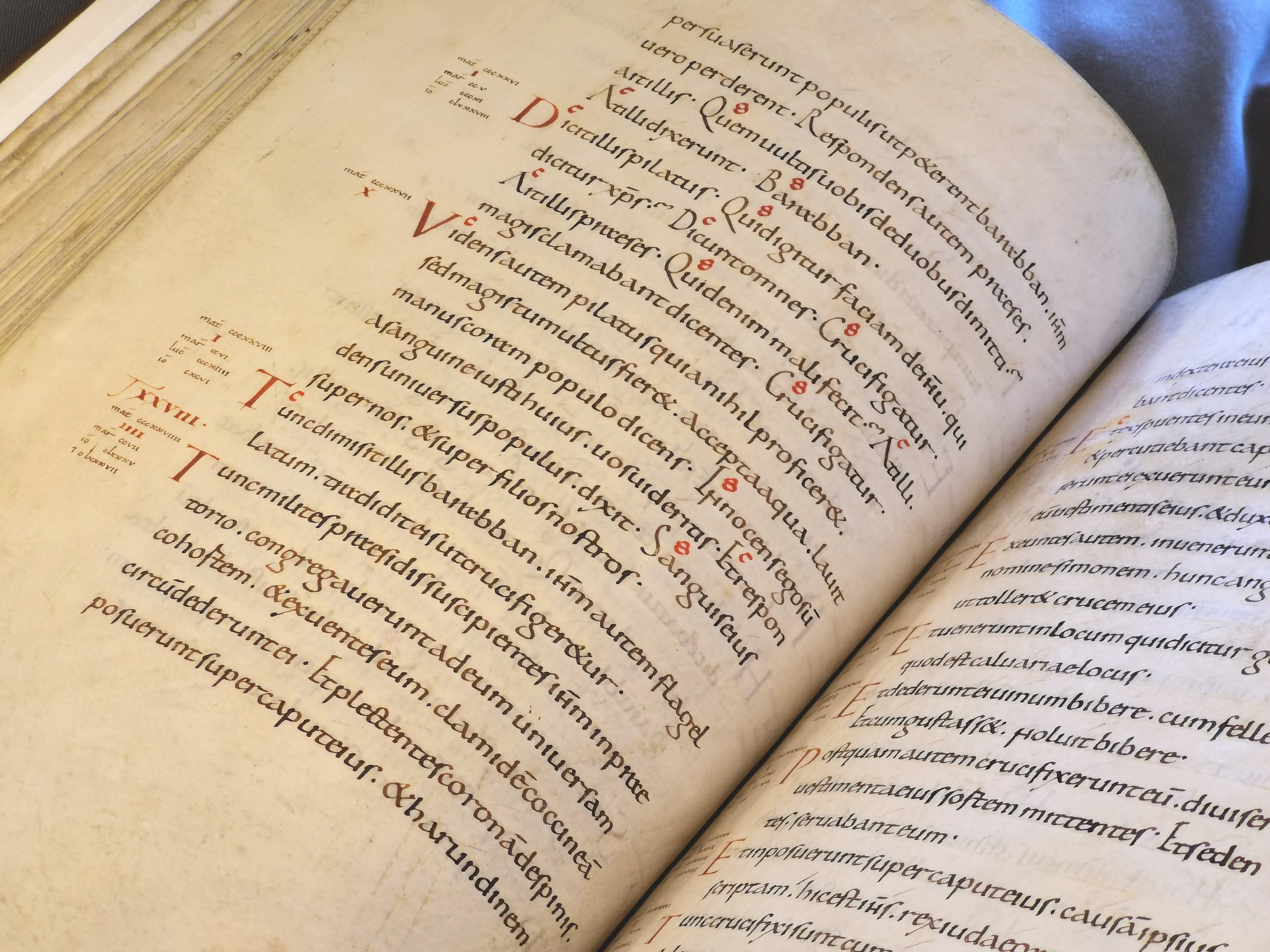

The codex shown here contains the Four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It was copied around 875 in a beautiful Caroline minuscule, probably by a monk of Saint-Amand Abbey, near Tournai and Valenciennes. In those days the Gospel lessons during the liturgical services of Holy Week (the week before Easter) were recited in one voice, by a single church official.

However, the Late Middle Ages saw a growing appreciation for dramatizing the Gospel lessons with the moving scenes of Christ’s Passion and Death. This started with voicing the texts by a basic cast of three officiants. In alternation and each with their own reciting tone and cadences a priest would chant the phrases of Christ, a deacon the narrative text of the evangelist and a subdeacon the 'part' of the other characters (Judas, Peter, the Crowd, etc.).

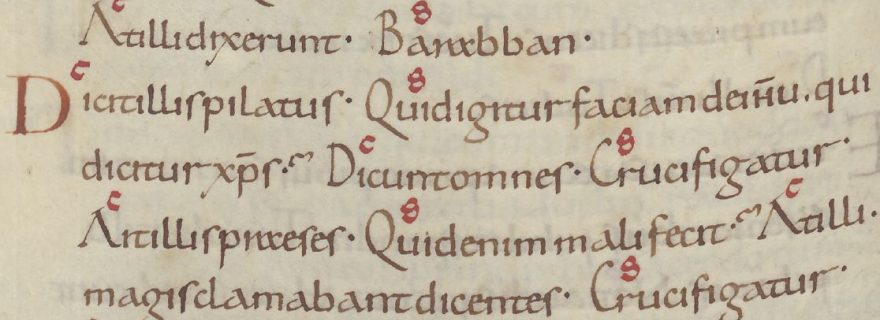

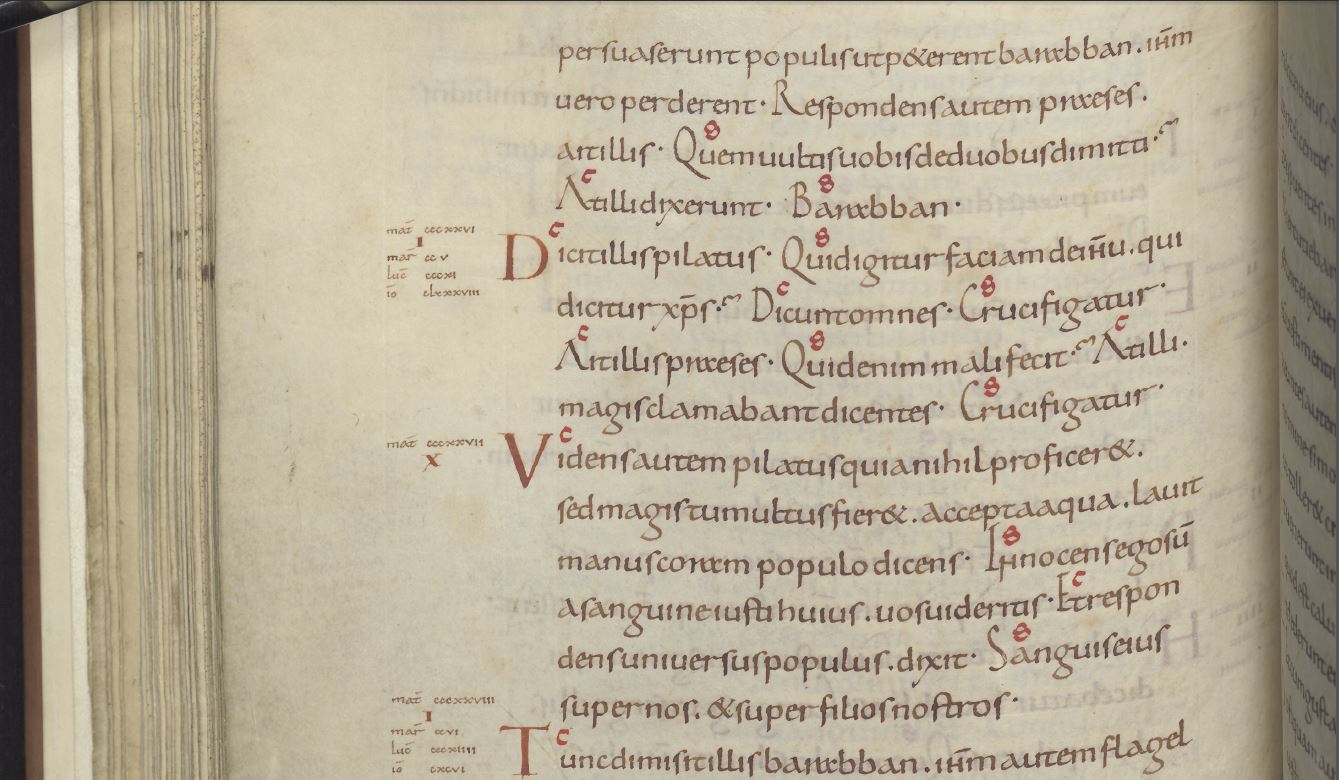

It was precisely to facilitate this liturgical use that the Passion stories in the Saint-Amand Gospel Book were afterwards ‘encoded’, probably in the fifteenth century. A Gothic hand marked the beginning of every line of text with a red letter: a c for the text of the evangelist, t for Christ’s lines and s for those of the other characters.

Concerning the meaning of the three letters several hypotheses have been formulated so far. According to Hiley, Western Plainchant (1993), the c, t and s in early sources must have been abbreviations for characterizations of the three reciting tones: c for celeriter (‘quickly’), t for trahere or tenere (‘slow’, ‘sustained’) and s for sursum (‘at a higher pitch’). Later the letters were reinterpreted as symbols for the reciting personae: c for chronista (evangelist), + (a cross developed from t) for Christ and s voor synagoge (other people).

The image above shows the passage from St Matthew's Gospel in which Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judaea, is negotiating with the Jewish people whom he will execute: Barabbas or Jesus. But not only St Matthew's Passion in this codex has been encoded with letters for melodic reciting; the other versions underwent the same treatment. This makes sense, because for almost fifteen centuries – until the introduction of the Roman Missal in the vernacular in 1973 – all four versions of the Passion were recited during Holy Week. St Matthew’s Passion could be heard on Palm Sunday, St Mark’s Passion and St Luke’s Passion on Tuesday and Wednesday respectively, and St John’s Passion on Good Friday, when the commemoration of Christ’s Death is the central element of the service.

For a complete digital version of the Saint-Amand Gospel Book (BPL 48) see the image repository of Leiden University Libraries: Digital Collections – This codex is famous for its illuminated opening pages; see my blog: Latin gospel book from the Franco-Saxon School – For a translation of the Latin on fol. 72 verso (Matthew 27:20 f.f.) see, for instance, www.latinvulgate.com