“A glimpse of knowledge”: Lessons from a Nineteenth-Century Arabic Textbook for Amharic

A rare Arabic primer to the Amharic language from 1872 CE provides unique insight into nineteenth-century trends in Egyptian education, Egyptian-Ethiopian relations, and the development of Arabic print culture.

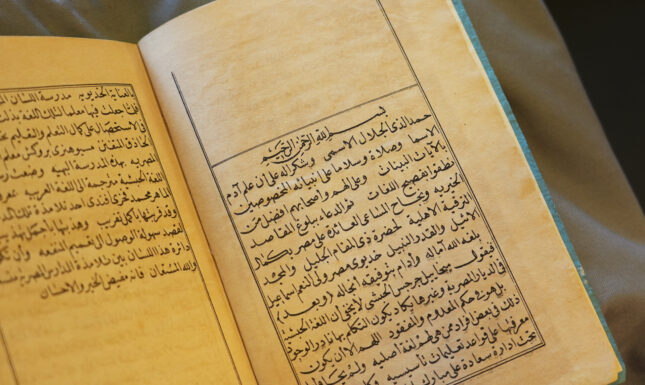

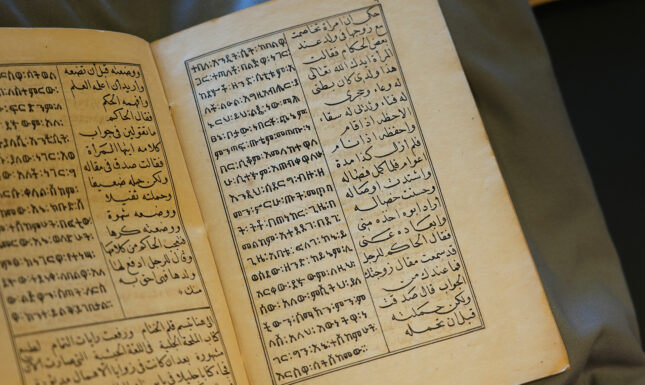

Leiden University Libraries holds a rare Arabic primer to the Amharic language from 1872-3 CE (1289 AH). Titled al-Mulḥa al-jalīya fī maʻrifat al-lugha al-Ḥabashīya [“A Lucid Glimpse into the Abyssinian Language”], this work by the Coptic Egyptian author Mīkhā’īl Jirjis al-Ḥabashī offers unique insight into educational trends and Egyptian-Ethiopian relations during the reign of Khedive Ismā‘īl (r. 1863-79). In this blog post, Johannes Makar, a Brill Fellow at the Scaliger Institute, discusses its historical value.

Reviving Amharic

“It is evident,” Mīkhā‘īl Jirjis al-Ḥabashī observes in his introduction, “that the Abyssinian language [i.e. Amharic] is nearly non-existent (ma‘dūm) in the Egyptian territories and elsewhere to the point that it is almost entirely lost, except perhaps among a few individuals for whom it is their native language” (3). al-Ḥabashī published the primer during his second or third year as a teacher at the School of the Ancient Egyptian Language (Madrasat al-Lisān al-Miṣrī al-Qadīm), commonly known as the School of Egyptology.

Founded in 1869, the School of Egyptology aimed to advance the study of Ancient Egyptian among local students, but it also offered instruction in three other languages: Coptic, German, and Amharic. Coptic held special significance as the final stage of Ancient Egyptian. German, in turn, offered the students access to the scholarly milieu of School Director Heinrich Brugsch (1827-1894). The decision to include Amharic is less obvious; in fact, a leading scholar previously suggested it might have been a mistake

in the documentary records (Reid, p. 331).

As al-Ḥabashī’s textbook confirms, an error it was not. Why Amharic—a language with no direct connection to Ancient Egypt—was taught remains unclear. It is no less striking that Khedive Ismā‘īl specifically ordered

that “dark-skinned” and “black boys” be trained in Amharic and Ancient Egyptian. It is plausible that the effort to revitalize Amharic was driven by strategic considerations. Interest in the language notably grew in tandem with Ismā‘īl’s ambitions to expand his influence in the Horn of Africa. Following the opening of the Suez Canal, Ismā‘īl launched an expedition into Ethiopian territory; however, open war with the Ethiopian Empire resulted in an Egyptian defeat in 1876. That al-Ḥabashī also taught Amharic at military academies

like Madrasat al-Bayāda reinforces this strategic motivation, though future research is needed to fully explore the underlying rationales.

The Author

al-Ḥabashī was a member of the Coptic Orthodox community in Egypt. The Copts had long-standing ties with Ethiopia as the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church fell under the jurisdiction of the Coptic Patriarch in Cairo. Given this connection, it is not surprising that Ismā‘īl called on the Coptic Patriarch to nominate an Amharic teacher from among his flock.

al-Ḥabashī, whose name means “the Abyssinian” or “of Abyssinia,” may have originated from a group of Copts in Ethiopia. In Cairo, he helped establish the Coptic Communal Assembly (al-Majlis al-Millī), an administrative body founded in 1873-74 with the aim of increasing lay representation in church and communal affairs. During this period, the Coptic laity also developed a growing sympathy for Ethiopia, with some critics during the 1876 war alleging that the Copts sided with Ethiopia against their own country (Cole, p. 145).

The Primer

In his primer, al-Ḥabashī notes that he originally composed the text in Amharic before Muḥammad Fakhrī, a student at the School of Egyptology, translated it into Arabic. According to the author, the work needed to broaden “the circle [of knowledge] concerning this language [i.e. Amharic] among the students” (3).

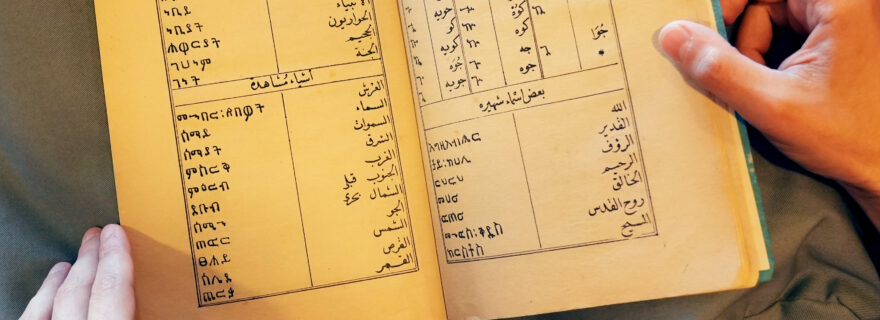

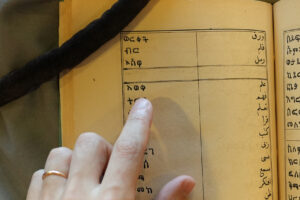

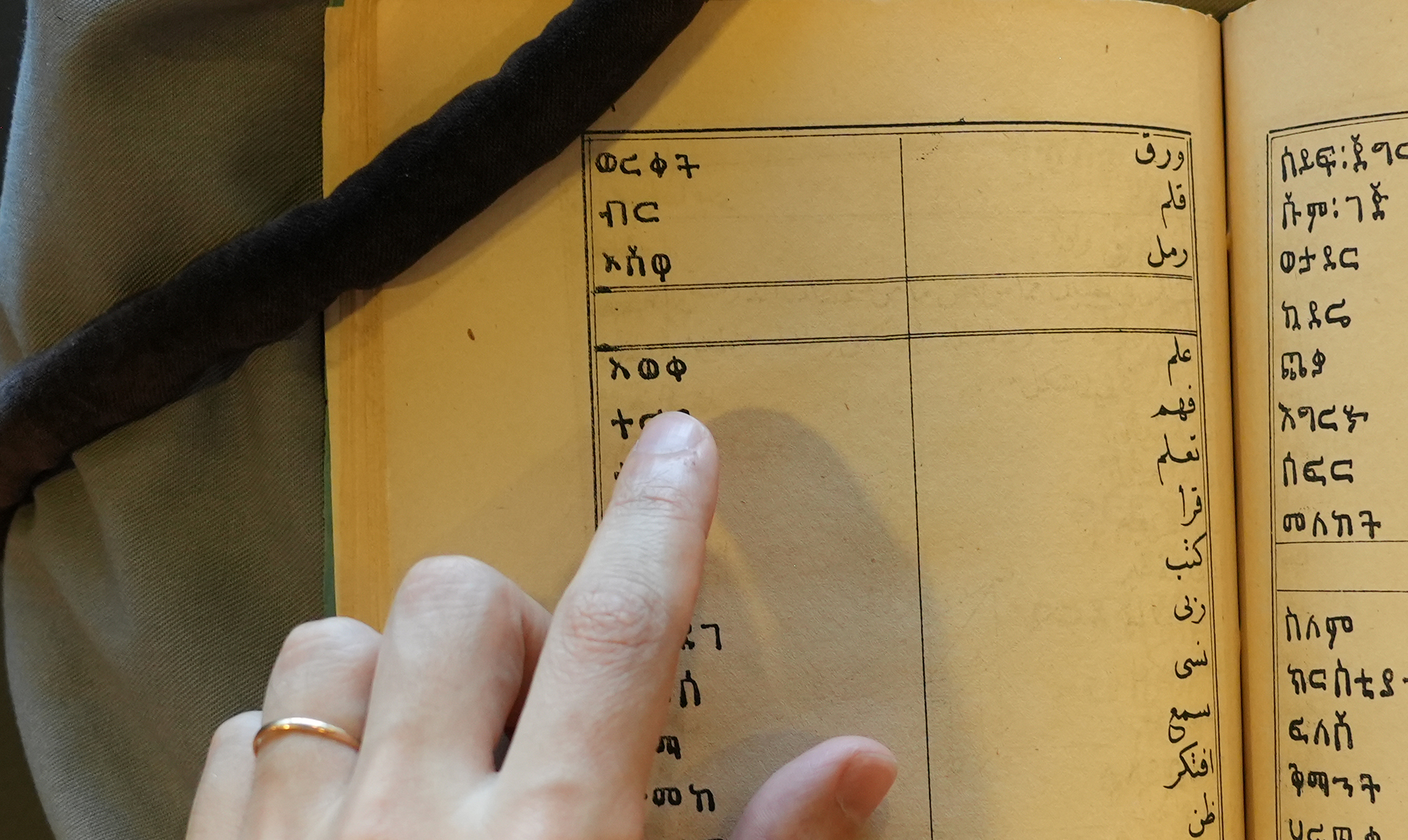

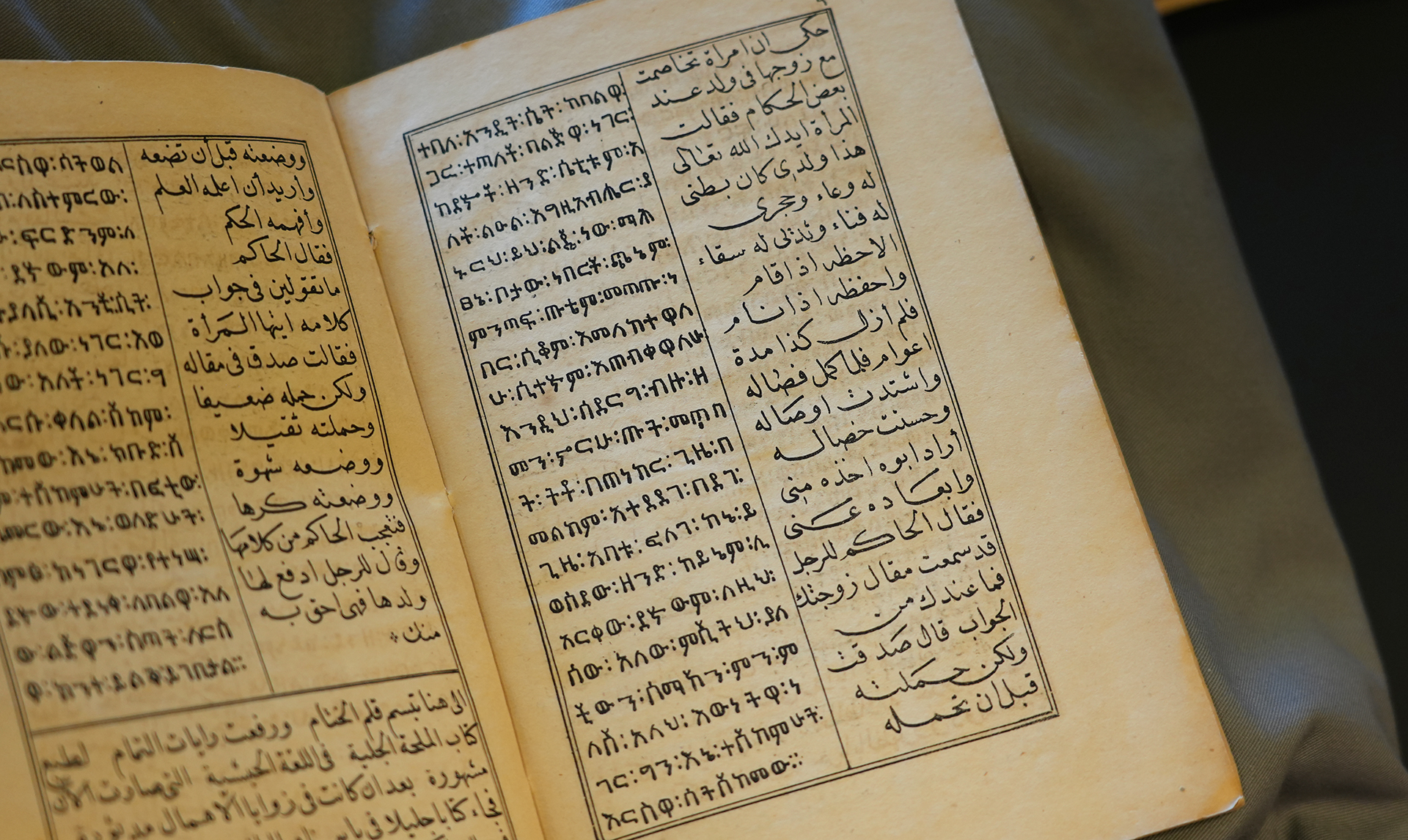

The primer is organized into three main sections: an introduction to the Amharic alphabet; glossaries of technical and practical vocabulary; and an overview of common expressions and dialogues. The textbook’s unusual focus on themes such as “categories of fire” (13) and its elaborate terminology regarding moral conduct (24-28) further hint at its application in military contexts.

The primer was published by the Egyptian Royal Colleges (al-Madāris al-Malakīya), whose publishing house also printed educational texts such as an Arabic grammar by the Egyptian scholar Ḥusayn al-Marṣafī (a copy of which is available at Leiden). al-Ḥabashī’s manual, a lithographic print measuring approximately 16.5 by 24.5 cm, reflects the ongoing transition from manuscript to print culture, as seen in its use of catchwords and a colophon, as well as imperfections like a missing header (49) and scribal errors (e.g. 7, 18).

The work also exhibits mixed cultural and religious influences. While it opens with an Islamic basmallah (a customary invocation of God’s name) and uses the Islamic hijrī calendar for dating purposes, the content itself reflects Coptic influence. For instance, in its first glossary, the attributes of God are presented in a manner typical of Christian Arabic tradition, listing al-Rā‘ūf instead of al-Raḥmān (both meaning “the Merciful”). It also lists the names of Christ (al-Masīḥ) and the Virgin Mary (Maryam al-‘Adhrā’) while omitting references to prominent Muslim figures (including Muḥammad). Nevertheless, the glossary goes on to list Islamic concepts likes al-ḥāwīrīyūn (a Quranic term used to refer to Jesus’ disciples) and awlīya’ (Muslim saints). Other terms such as “Nayrūz” (Coptic New Year), as well as a separate lexicon for the Coptic (rather than Islamic or Gregorian) months, uphold the close relation between the Coptic and Ethiopian calendars (15-16).

In all, the primer provides a valuable glimpse into a lesser-known chapter of Egyptian history under Khedive Ismā‘īl, who famously saw himself as a steadfast modernizer and patron of learning—a sentiment which al-Ḥabashī echoed. In this vein, we may conclude with the author’s own closing words:

At this point, the quill that brings closure rejoices,

and the banners of completion are raised

[….]

May the days be filled with the sunlight of His Eminence [Khedive Ismā‘īl]

And the night illuminated by the moon of His Reign.

May the lives of His noble descendants be prolonged, and

may they be guarded by [God’s] ever watchful eye (91-92).

___________________

About the Author: Johannes Makar is a PhD Candidate in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University. He is currently a Brill Fellow at the Scaliger Institute, Leiden University.

Acknowledgement: Meseret Oldjira offered guidance with questions concerning the Amharic text. Adam Mestyan and Kasper van Ommen read and commented on the essay.

Further Reading:

For more information about the Cairo School of Egyptology: Donald M. Reid, Whose Pharaohs?: Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), esp. 116-118; Amal Hilal, “Les premiers égyptologues égyptiens et la réforme,” in Entre réforme sociale et mouvement national: Identité et modernisation en Égypte (1882-1962), ed. Alain Roussillon (Cairo: CEDEJ - Égypte/Soudan), 337-350.

Titlepage |

1 |

Introduction [in Arabic] |

2-3 |

Introduction [in Amharic] |

4-5 |

Single letters (ḥurūf mufrada) |

6 |

Compound letters (ḥurūf murakkaba) |

6-10 |

Prominent names (ba‘ḍ asmā’ shahīra) |

10 |

Theological concepts (asmā’ mushāhada) |

11-12 |

The elements (fī-l-‘anāṣir) |

12-13 |

Natural concepts (fī asmā’ al-ṭabā’i‘) |

13 |

Categories of fire (anwā‘ al-nār) |

13 |

The seasons (asmā’ al-fūṣūl) |

13-14 |

Concept of time (asmā’ al-zamān) |

14 |

Concepts of day (asmā’ al-awqāt) |

14-15 |

Months (asmā’ al-shuhūr) |

15 |

Seasons and festivals (fī-l-mawāsim wa-l-a‘yād) |

15-16 |

Days of the week (ayyām al-usbū‘) |

16 |

The humankind (fī-l-jins al-basharī) |

16-17 |

Family and relatives (fī-l-ahl wa-l-aqārib) |

17 |

The human body (fī jism al-basharī) |

18-22 |

Physical disabilities (fī-l-‘uyūb al-ṭabī‘īya) |

22 |

Illnesses (fī-l-amrāḍ) |

23 |

Emotions (fī ḥarakāt al-nafs) |

24 |

Virtues and vices (fī-l-faḍā’il wa-radhā’il) |

24-28 |

Metals (fī-l-ma‘ādin) |

28-29 |

Fruit trees (fī-l-ashjār al-muthmira) |

29 |

Vegetables and legumes (fī-l-nabāt wa-l-buqūl) |

29-30 |

Four-legged animals (fī-l-ḥayawanāt dhawāt al-arbi‘a) |

30-32 |

Birds (fī-l-ṭuyūr) |

32-33 |

Insects (fī-l-ḥasharāt) |

33-34 |

Clothing (fī-l-malbūsāt) |

34-35 |

Food (fī-l-ma’kūlāt) |

35-36 |

Eating utensils (adawāt al-sufra) |

36 |

Places and dwellings (fī-l-amākin wa-l-masākin) |

36-37 |

House-related concepts (fīmā yat‘alliq bi-l-bayt) |

37-38 |

House essentials (fī asās al-bayt) |

38-39 |

Artisans (fī arbāb al-ḥiraf) |

39-41 |

Cardinal numbers (fī-l-a‘dād al-aṣlīya) |

41-42 |

Ordinal numbers (fī-l-a‘dād al-tartībīya) |

42-43 |

Pronouns [with conjugations] (fī-l-ḍamā’ir) |

44-45 |

Antonyms (fi kalimāt mutaḍāda) |

45-46 |

Colors (bayyān al-alwān) |

47 |

Rank holders (fī arbāb al-rutab) |

47-48 |

Religions (fī-l-adyān) |

48 |

School utensils (fī adawāt al-madrasa) |

48-49 |

[verbs (al-af‘āl)], note: header missing |

49-65 |

Commonly used expressions (fī ba‘ḍ jumal ma’lūfat al-isti‘māl) |

65-77 |

Dialogues 1-10 (al-nawādir) |

77-91 |

Colophon |

91-92 |