A forbidden book

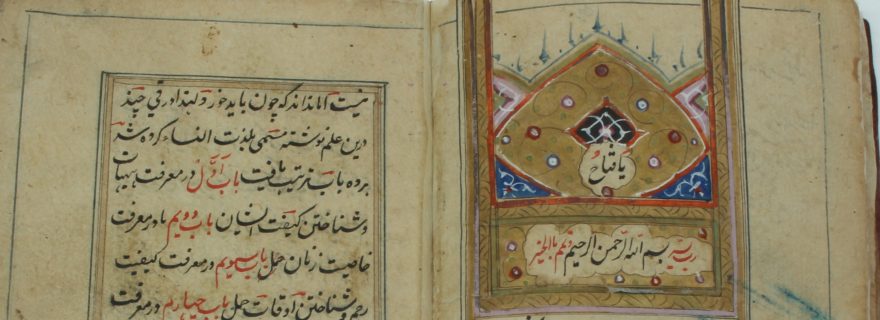

The current Leiden University Libraries exhibition ‘Sanskrit – Asia and Beyond’ features a richly illustrated Persian translation of the Kamasutra from the Mughal period. This manuscript with its abundant erotic drawings was not always easily accessible.

Some books have been read so often that over time they have accumulated many traces of use. Apart from incrusted dirt and abrasive damage which may have actually rounded the corners, there often is evidence of professional repair or homecrafted mends. Whenever a book is brought in for conservation treatment, we carefully decide how best to preserve the historical evidence. It is not necessarily our aim to make the object more beautiful by removing old patches of repair, not even when the item is selected for exhibition purposes. When old repairs are damaging to the original materials or hamper future use, intervention is needed. Sometimes, however, they provide interesting information that we may want to preserve.

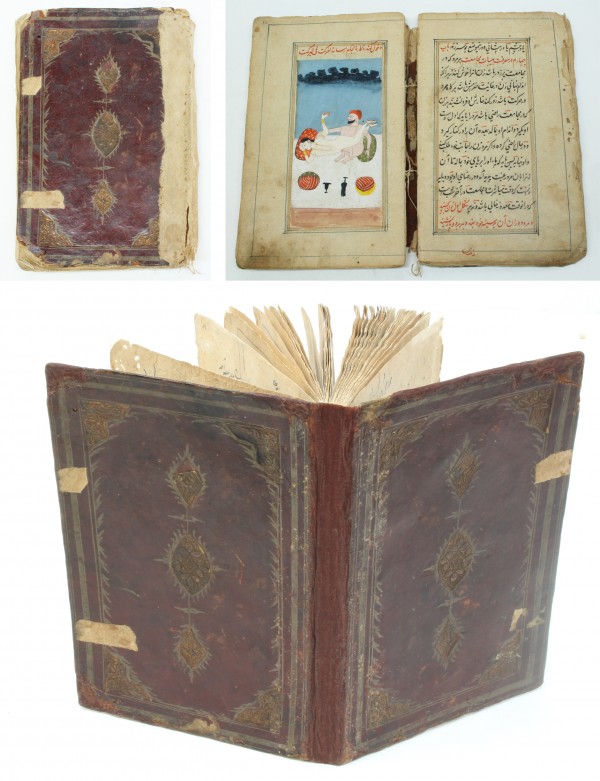

Such was the case with a Persian manuscript, an erotic handbook by Ziya Bakhshi (Or. 14.558). The manuscript was written and illustrated around 1800 in India. Selected for the UBL exhibition ‘Sanskrit – Across Asia and Beyond’, together with two other volumes on the same topic, the damaged manuscript required stabilisation prior to installation. Its sewing was broken, some pages were loose and had torn edges, and the binding’s spine was missing. As a replacement, a piece of textile of a tabby weave was pasted onto the spine of the textblock and over the edges of the boards. The corners of the boards were worm-eaten and abraded and additional patches of paper were stuck onto the fore-edges of the cover.

The textile repair lining was already detached from the gatherings. To improve the manuscript’s condition, the folios would be repaired and resewn. Then, in order to re-attach the boards to the textblock, the extending parts of the textile pasted onto the outside of the board had to be removed. This would also reveal the tooled and gold painted leather decoration close to the joints of the covers.

During this stage of the treatment, when the manuscript was separated from its binding components, the boards lay loose on the workbench. This way, it was possible to observe an interesting similarity in the way the paper patches were applied to the fore-edge of the boards. They were pasted onto the leather at the same height and didn’t appear to cover any wormholes or other damage. In fact, it seemed that the patches were remnants of two paper strips which used to connect the front and the back board. If so, these strips would not at all have functioned as a repair or support. Instead, they provided a lock on the manuscript. Admittedly, this lock could quite easily have been broken, but then at least there would have been clear evidence of trespassing. This would have alarmed the owner that someone else had sought access to this piquant manuscript.

Though it remains unknown when and by whom this paper lock was added to the volume, as a material witness to a certain phase in the manuscript’s history it is an important element. With the recent conservation treatment, it was therefore preserved intact and untouched. What is more, now that the binding has regained its functionality and the visually disturbing cloth repair has been removed, it is easier to recognise these paper strips for what they are.

The manuscript will be on display in the University Library until 5 September 2017.

Kamasutra by Ziya Bakhshi (Or. 14.588), above before treatment, bottom image after treatment