A busy route: a story of airmail between the Dutch East Indies and the Netherlands.

The Hoekstra-collection contains more than 900 items of ephemera and memorabilia, but among the most striking items is a set of mysteriously empty envelopes.

The Dutch East Indies was one of the last colonies of the Netherlands. It remained partly under Dutch control until 1963. In the 17th or 18th century, a VOC-sailing vessel spent about eight months at sea to reach the Malay archipelago – if it got there at all. By the end of the nineteenth century, thanks to rapid technological advances, travel time was reduced to one month by steam or motor ship. The steam shipping companies Rotterdamsche Lloyd and Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland covered transport of both civilian passengers and military staff, as well as the shipping of postal items between the Netherlands and Batavia (Jakarta) from the 1870s onward. From Batavia, smaller ships of the Royal Packet Navigation Company (KPM) would take both passengers and mail to a number of smaller, in-country ports. Despite the fundamental transition from sailing vessel to steam- and motor ship, both were eventually surpassed by the Royal Dutch Airlines (KLM), which performed its first flight from Amsterdam to Batavia in October 1924, carrying 281 letters destined for the archipelago. Although the ocean liner still remained the major means of transport for people, aviation took over the mail service, operating a weekly flight from Amsterdam to Batavia by 1931.

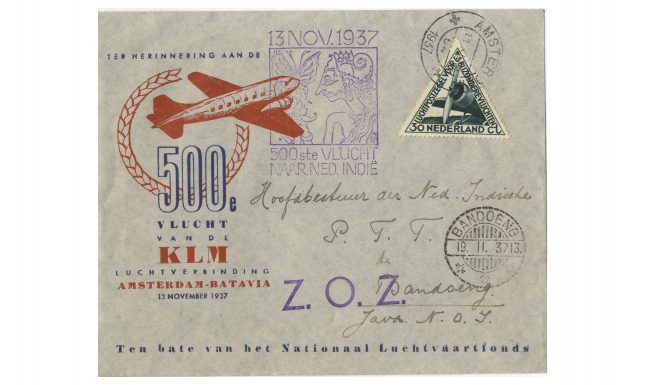

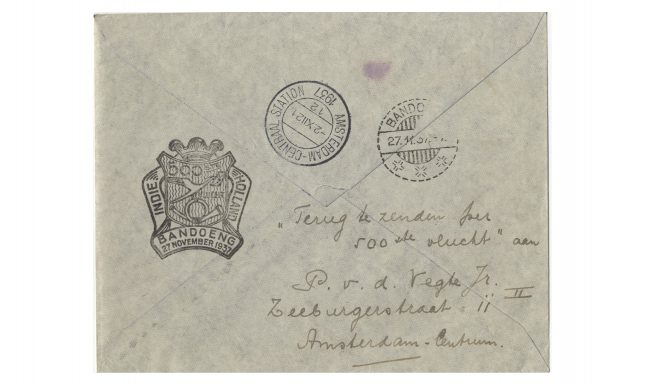

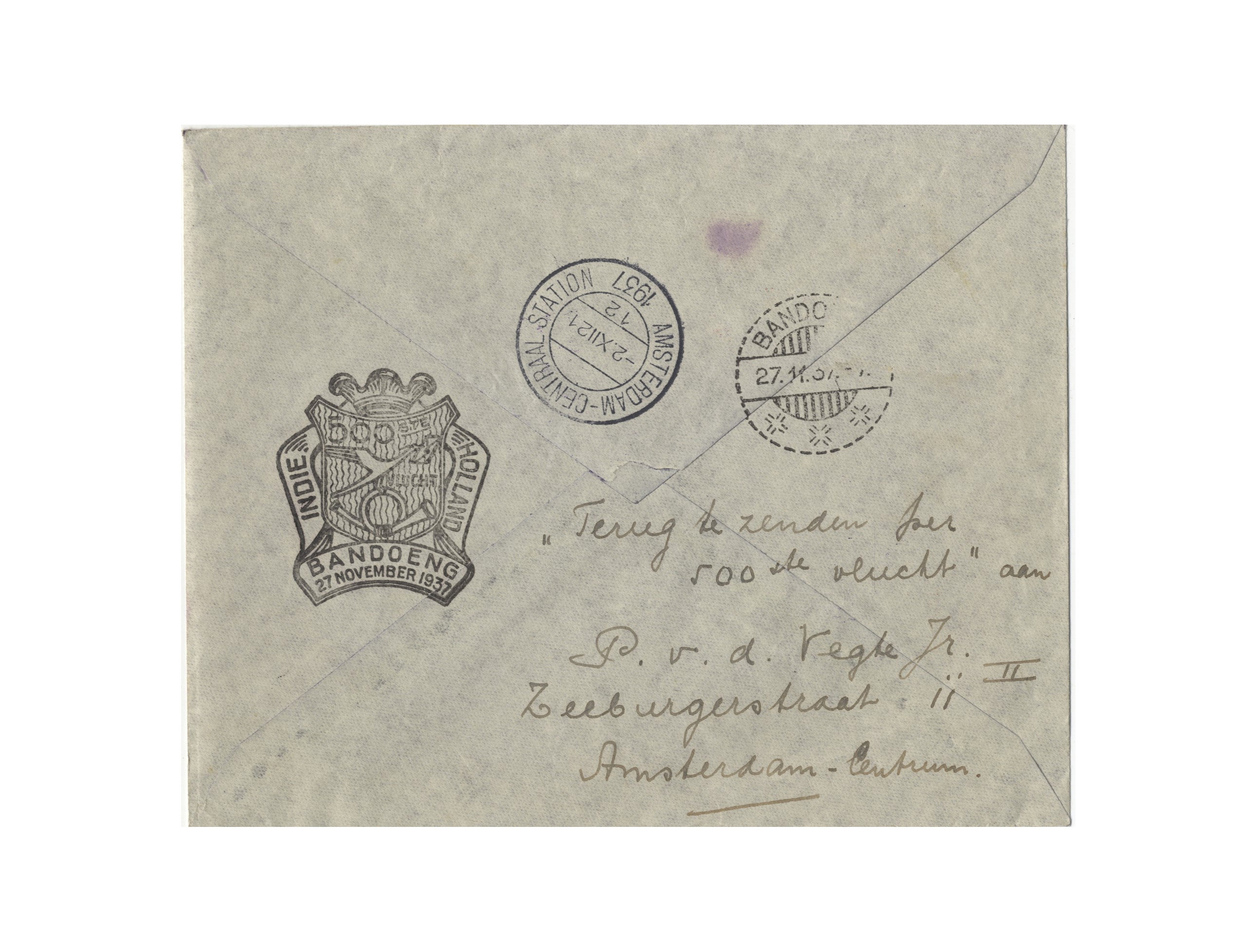

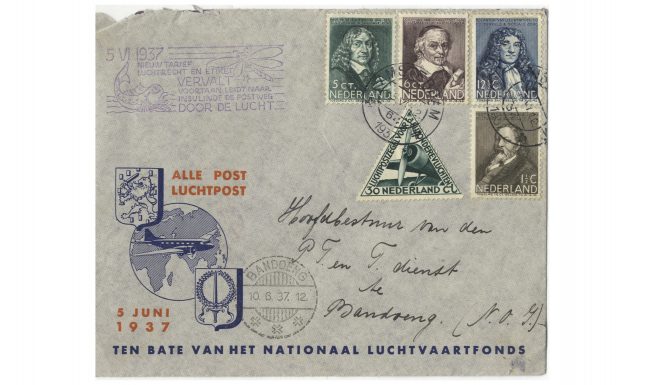

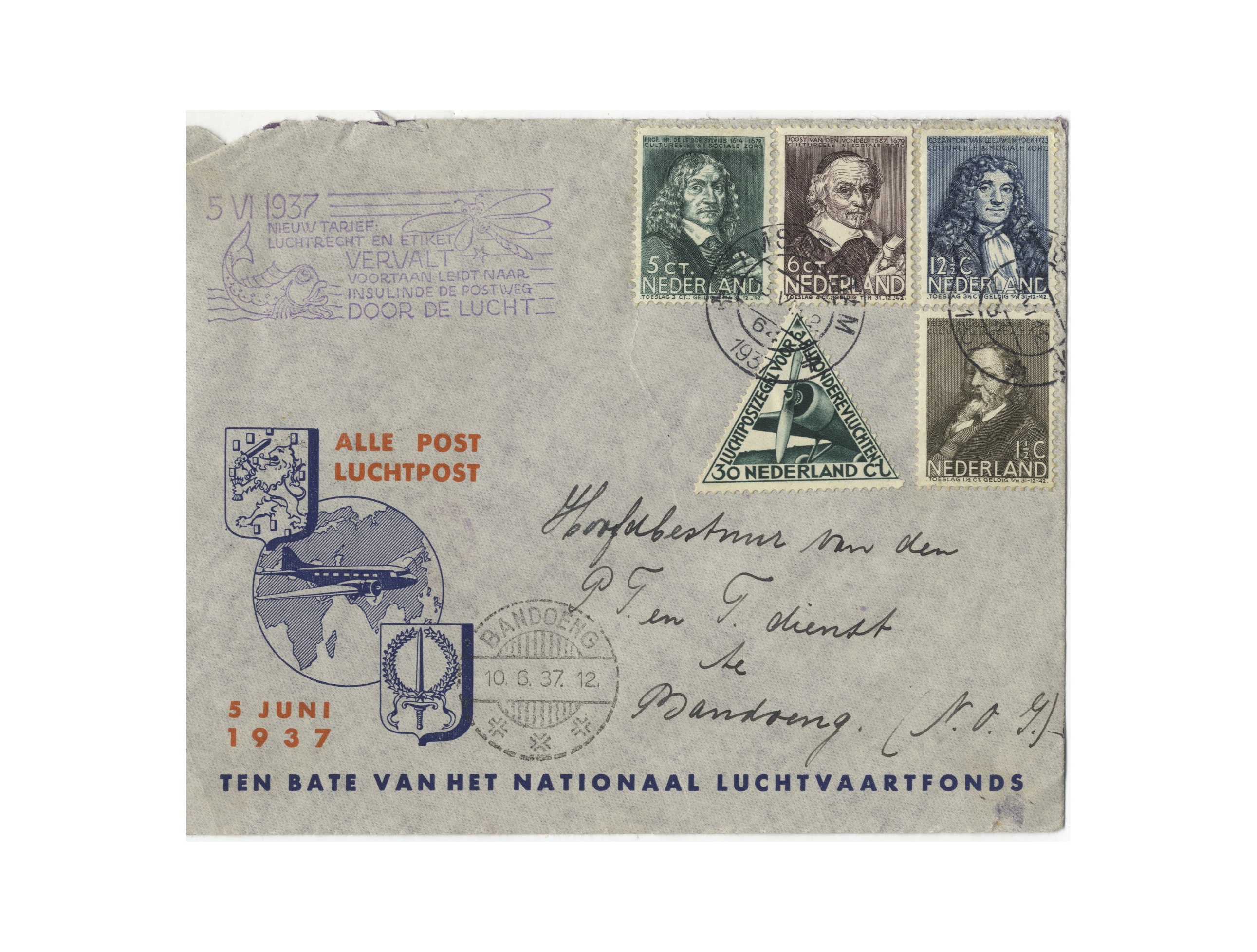

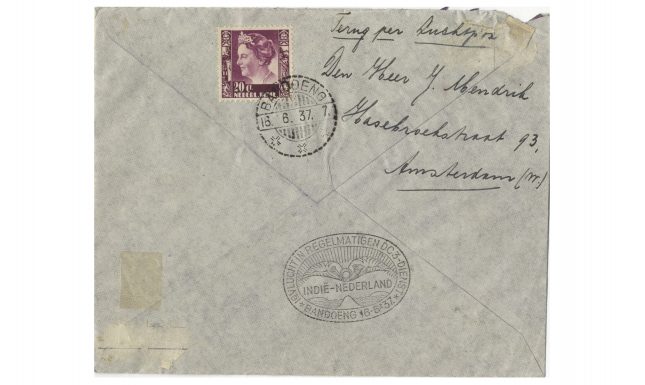

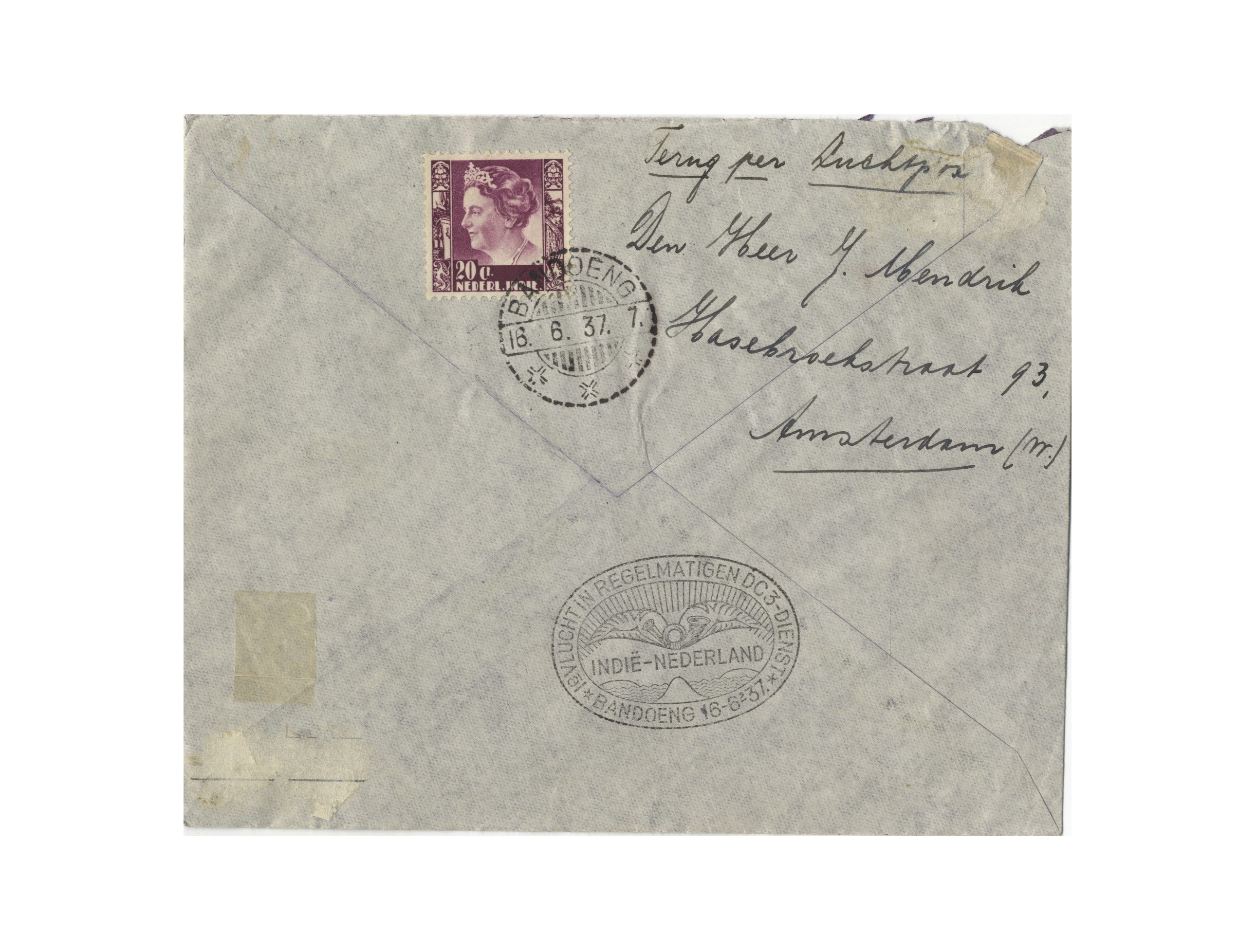

The first decades of the 20th century form an era of major changes in the field of transportation to and from the Dutch East Indies. The comprehensive collection that A. Hoekstra donated to Leiden University Libraries between 2016 and 2019 provides unique insight into this era. The Hoekstra-collection contains more than 900 items of ephemera and memorabilia, like menu cards, passenger lists, picture postcards, colourful folders, commemorative coins and onboard-money, match-boxes and even cigar bands. Among the most striking items, however, is a set of mysterious envelopes that very much puzzled me and curator Doris Jedamski. The envelopes were extremely light and still closed. We decided to open them to find out about their contents, but, to our surprise, all we found were blank sheets of paper, or, in some cases, a card with the address that was also written on the envelope itself.

The obvious presence of both postal stamps and postmarks is proof that these letters indeed made the journey, each and every one of them, apparently, on a commemorative flight, for instance, the first regular weekly flight and the 500th KLM flight to Batavia. But why did the senders never include any messages in their envelopes? Considering the relatively high postage rates, it seems a waste of money and quite strange to send a blank sheet of paper. The answer is to be found in the world of the philatelists. Collectors of postal items at that time were eager to get every new stamp, mark or envelope that the Royal Dutch Post and Telegraph Corporation (PTT) published. Also, for every commemorative flight, a so-called ‘first day cover’ was made. Most of those collector’s items were also available in Dutch bookstores and post offices. Die-hard philatelists, however, wanted first day covers that had truly travelled to the Dutch East Indies - and back, as this was the only way to receive the locally produced postal stamps and postmarks of the Dutch East Indies. Oddly enough, the Dutch mail service provided a special service to meet those wishes. Any collector could send an envelope – with or without content – to the headquarters of the mail service in Bandung, he only had to add a return address and the remark ‘return to sender’. On arrival, the letter would be sent back to the Netherlands, complete with the desired in-country postal stamp and postmark.

One may wonder why a busy agency like the PTT was willing to provide such a time-consuming service. There was a pragmatic reason for it. With large quantities of postal items sent by philatelists on every commemorative or special flight, those collectors, in fact, helped to maintain the frequent airmail service. They were regular customers paying rather high rates for the postal service. This lucrative source of income helped to keep up the regular flights operated by the Royal Dutch Airlines. One may say that these seemingly mysterious envelopes helped hundreds of Dutch families to stay in regular airmail contact with their loved ones, living 12.000 kilometres away.

Many thanks to Marc Dierikx for his explanation of the first day covers

Author: Geke Burger MA is a staff member at the Leiden Special Collections, where she is responsible for cataloguing primary source-material from the Dutch East Indies.